I’ve turned the “reply” function here back on — or at least no logon to WordPress should be required to leave a comment — to see what happens. So far, unwanted replies are coming in. We’ll see whether that becomes a torrent.

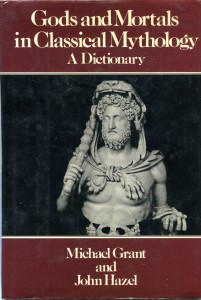

Another specialized dictionary that’s a prized book on my shelves: the hardback edition of Gods and Mortals in Classical Mythology by the tireless Michael Grant and John Hazel, first published in the UK in 1973. The Dorset Press put out my edition in 1985.

Another specialized dictionary that’s a prized book on my shelves: the hardback edition of Gods and Mortals in Classical Mythology by the tireless Michael Grant and John Hazel, first published in the UK in 1973. The Dorset Press put out my edition in 1985.

In the front cover I wrote my name, and “New York City, Aug 29, 1986.” I found it on a remainder table at the Barnes & Noble on Fifth Avenue back when that place was a destination, rather than just a large store in a large nationwide chain (and which closed last year anyway). I bought it as an upgrade to a paperback version of the book I acquired ca. 1984 in Nashville.

Acquiring the hardback allowed me to give the paperback to my college friend Rich, who’d expressed an admiration for it during a visit, and wanted it to look up Classical references in the Continental philosophy and the writings of other Germanic thinkers he’s interested in.

Me, I just enjoy reading about Antiquity. Gods and Mortals in Classical Mythology is an exceptional reference for that purpose.

Some excerpts, picked at random, show its richness. Such as wonderful detail about well-known characters:

Traditions vary about the appearance of the Gorgons. One the one hand, they are sometimes described as beautiful, and it was said that Athena gave Perseus the power to kill Medusa because she had boasted of excelling the goddess in beauty. Ancient art, on the other hand, depicts them with hideous round faces, serpentine hair, boar’s tusks, terrible grins, snub noses, beards, lolling tongues, staring eyes, brazen hands, a striding gait, and sometimes the hindquarters of a mare.

Or giving more obscure characters a mention:

Halirrhothius: Son of Poseidon and a nymph, Euryte. Near the Acropolis in Athens, he raped Alcippe, a daughter of Ares and Aglaurus, and for this Ares killed him. The god was arraigned by Poseidon at a court which met on the spot. This was the legendary origin of the court named Areopagus (Hill of Ares), which tried cases of homicide at Athens: it acquitted Ares of guilt.

And offering variations on the stories, which shows that that’s the way storytelling usually works. The book has this to say on the death of the hunter Orion, who hunts even now in the winter sky with his faithful Canus Major and Minor following him.

Orion next went to Crete, where he hunted in Artemis’ company, but Eos, goddess of the dawn, fell in love with him and carried him off. The gods, and particularly Artemis, were jealous that a goddess should take a mortal lover, and on the island of Delos… Artemis killed Orion with her arrows.

She is likewise associated with other variant accounts of Orion’s death. According to one of them, he died because he rashly challenged the goddess at discus-throwing; and another story recounted that she shot him for trying to rape Opis. Again he was said, while clearing Chios of wild animals, to have tried to rape Artemis herself, but she brought from the ground an enormous scorpion which stung him to death.

Or else she did this because she was afraid that he would kill all the animals on earth; or, alternatively, she actually contemplated marriage with Orion, whereupon her brother Apollo tricked her into killing him by pointing to an object far out at sea and betting that she could not hit it. She tried and succeeded, but the target she had hit turned out to be Orion’s head, for he was swimming or wading far from shore. In her grief she place her beloved in the sky as a constellation.