No matter how much you prepare to visit a city you don’t know well — and I try not to overdo it — surprises will turn up. Details you’ll only encounter in person. Such as Denver’s Rainbow Row.

That’s just my name for it, borrowed from the genteel Rainbow Row of Charleston. Denver’s version is not genteel. For one thing, it’s across the street from the 488,000-square-foot Denver Justice Center. That is, the city/county jail.

The colorful buildings all house bail bondsmen. It’s only speculation, but I’d guess that one of them painted its building a bright color to stand out, then the others did.

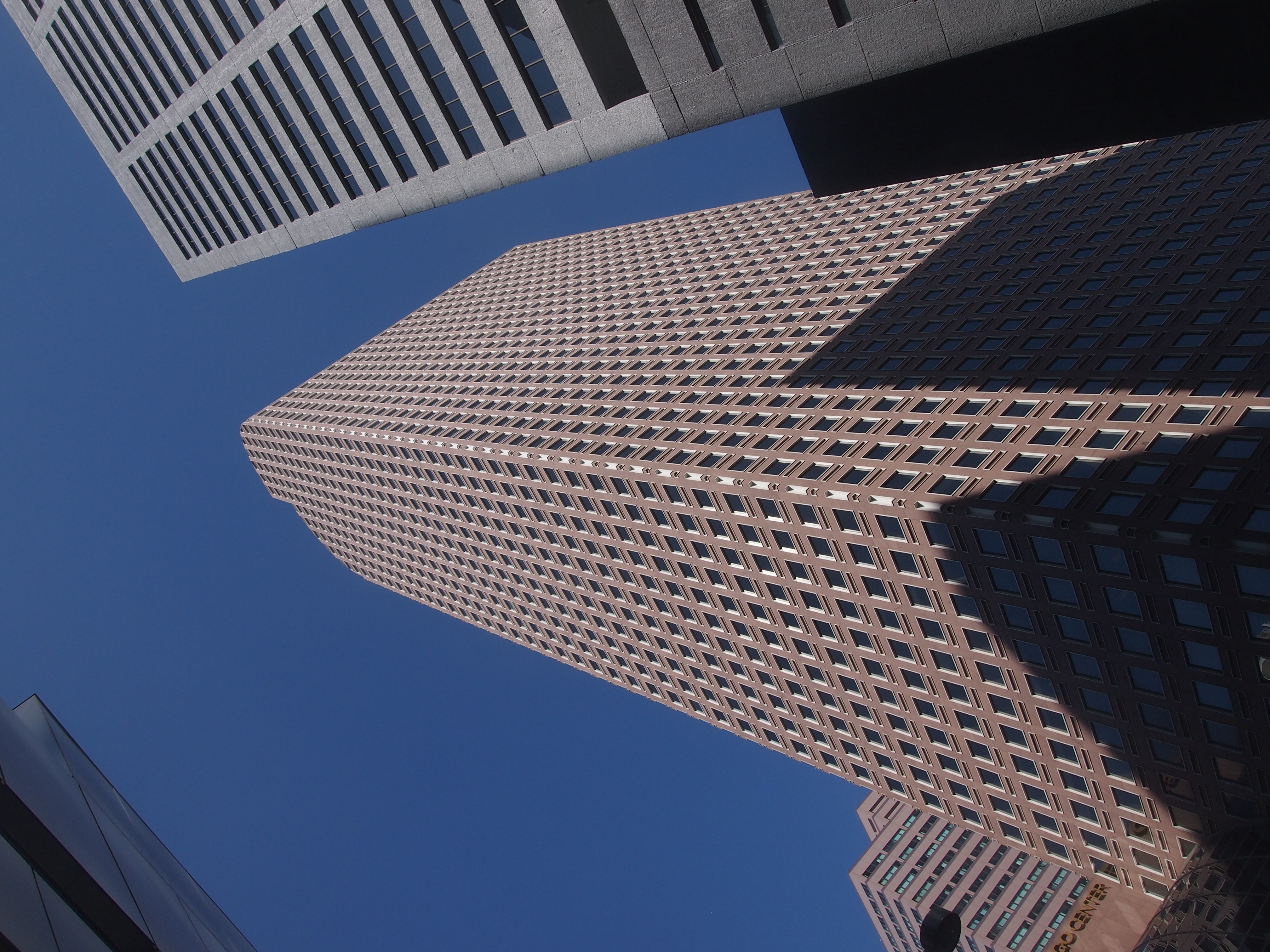

Speaking of colorful structures, not far away is the Denver Central Library.

More of a pastel effect. Though maybe “pastel” is too banal a term when you’re aiming to challenge assumptions about public spaces and discourse, or fracture public library paradigms, or something.

More of a pastel effect. Though maybe “pastel” is too banal a term when you’re aiming to challenge assumptions about public spaces and discourse, or fracture public library paradigms, or something.

Anyway, Michael Grave Architecture & Design, which designed a major expansion of the library in the 1990s, notes: “This project, won through a design competition, included the preservation and renovation of the 1956 147,000 SF modernist library by Burnham Hoyt, and a 390,000 SF expansion. The expansion is composed as a series of elements to allow the existing building to read as one part of a larger composition.”

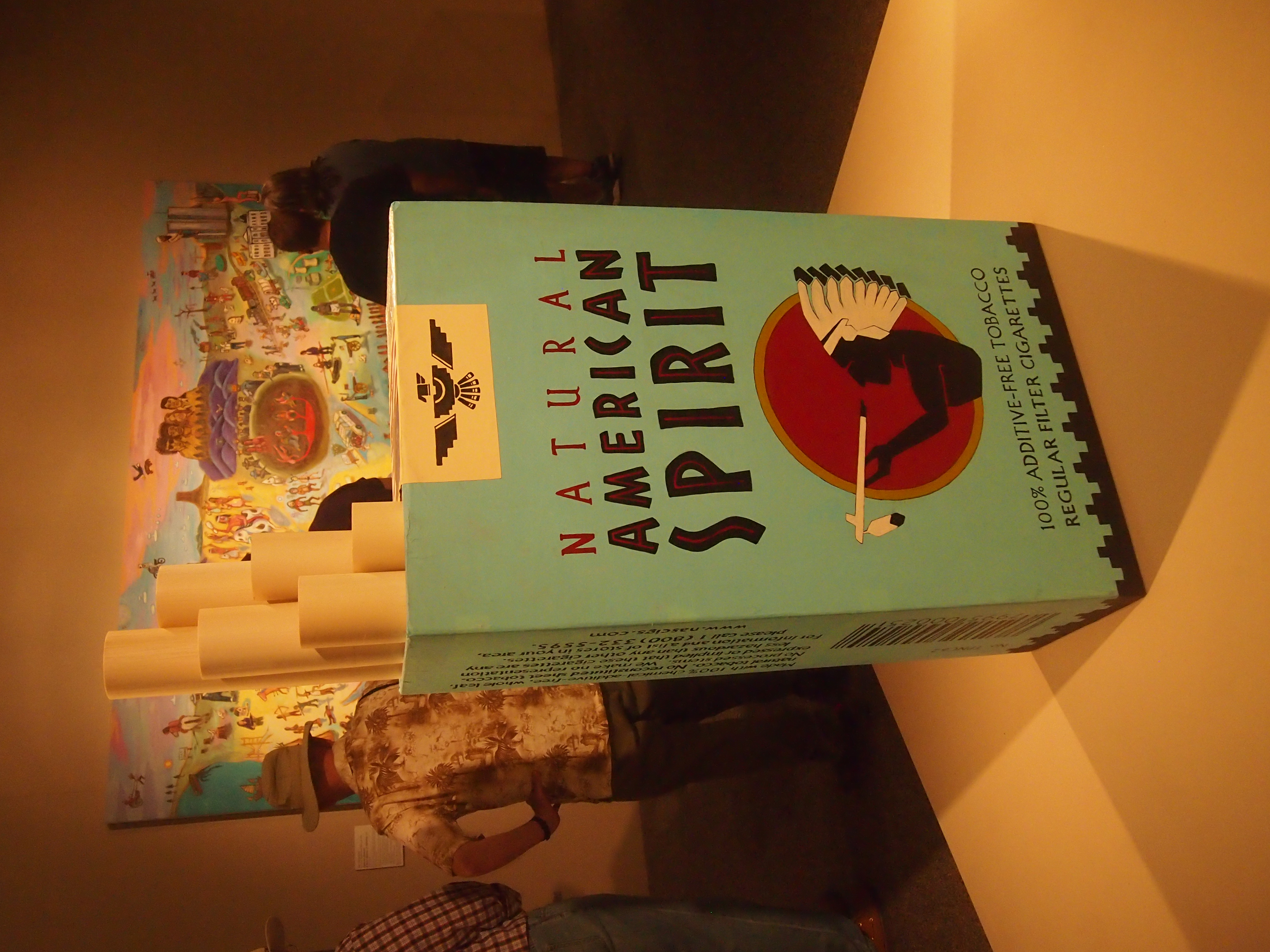

The library is across the street from the Denver Art Museum. Outside the museum is this sculpture.

Looks familar. Yes indeed, it’s a Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen work, “Big Sweep” (2006). (What, that wasn’t the name of one of Raymond Chandler’s best books?)

Looks familar. Yes indeed, it’s a Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen work, “Big Sweep” (2006). (What, that wasn’t the name of one of Raymond Chandler’s best books?)

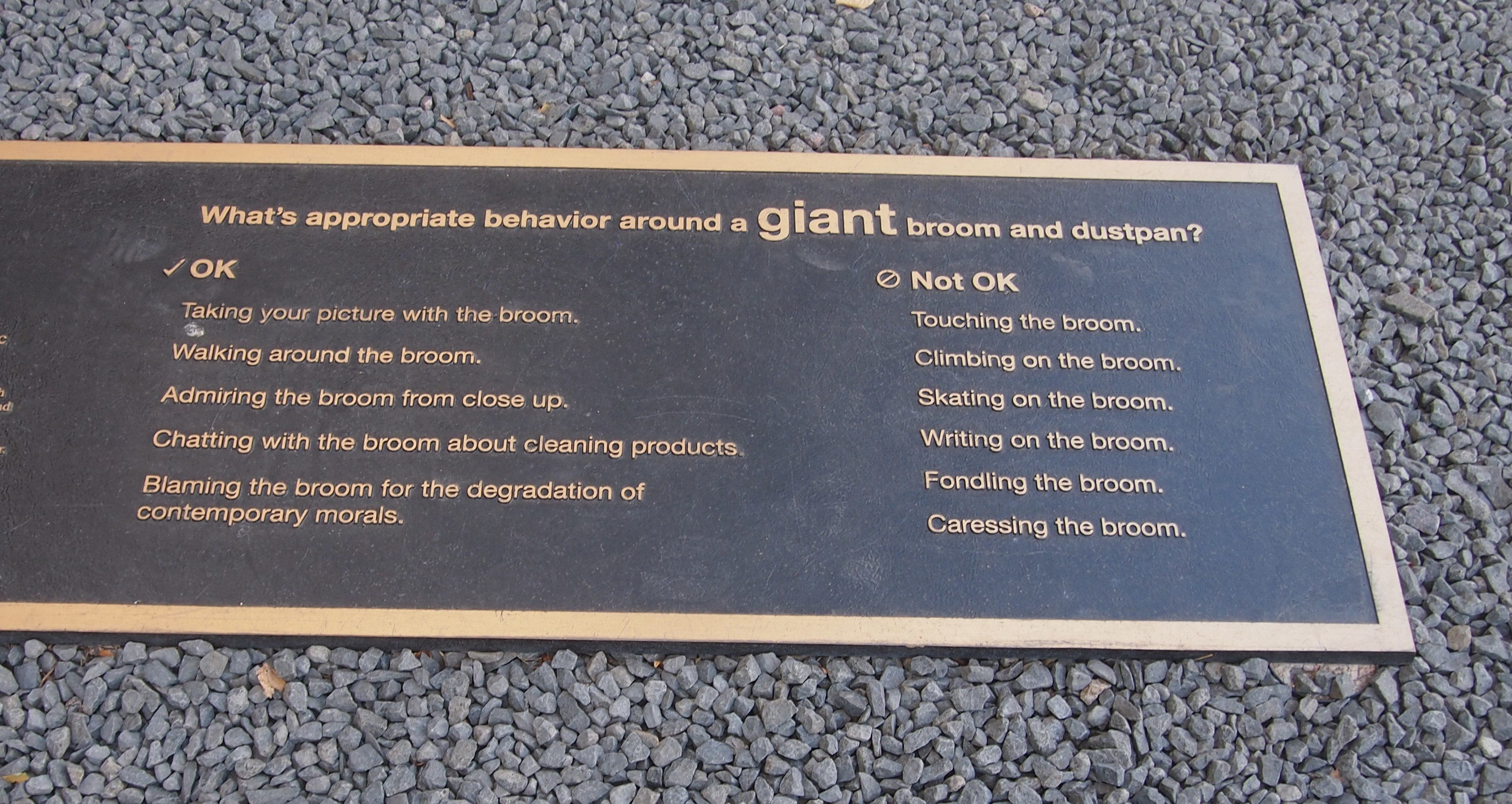

Art etiquette is right there in bronze, next to the work.

After visiting the museum, I spent a while at the Friendship Powwow and American Indian Cultural Celebration just outside on the plaza. Featuring dancers.

After visiting the museum, I spent a while at the Friendship Powwow and American Indian Cultural Celebration just outside on the plaza. Featuring dancers.

And drummers. Cool.

And drummers. Cool.

Outside of Union Station, I saw a Tesla Model X. Haven’t seen those very often. Ever, actually.

Outside of Union Station, I saw a Tesla Model X. Haven’t seen those very often. Ever, actually.

Close inspection shows that it belongs to the Crawford Hotel, which is part of Union Station. An upper-crust guest shuttle, no doubt.

Close inspection shows that it belongs to the Crawford Hotel, which is part of Union Station. An upper-crust guest shuttle, no doubt.

On my last day in town, I worked in some shared office space — all the rage right now. I prefer my own office most of the time, but it was pleasant space. I didn’t mind working there for a few hours. Had a nice outdoor component, for one thing, with the Front Range off in the distance.

I worked at this counter. People came and went, preparing light eats for themselves.

I worked at this counter. People came and went, preparing light eats for themselves.

Above the counter was this. A hell of a light fixture, I’d say. Machine Age chic for Millennials.

Above the counter was this. A hell of a light fixture, I’d say. Machine Age chic for Millennials.

In the same room were old machines made into illuminated works of art. Such as this typewriter + light bulbs, the likes of which I’d never seen before.

In the same room were old machines made into illuminated works of art. Such as this typewriter + light bulbs, the likes of which I’d never seen before.

A semi-circular, very old (late 19th century) Hammond machine. Looks like a 1b. Non-qwerty. Light bulbs added for effect, presumably.

A semi-circular, very old (late 19th century) Hammond machine. Looks like a 1b. Non-qwerty. Light bulbs added for effect, presumably.

Then there’s this curiousity. Again, light bulbs added.

A 19th-century medical device. Reminds me of the Museum of Questionable Medical Devices in Minneapolis, now unfortunately closed.

A 19th-century medical device. Reminds me of the Museum of Questionable Medical Devices in Minneapolis, now unfortunately closed.

I had the good fortune to visit that museum in 1998, and retain a pamphlet from it to this day.

The machine I saw in Denver is a specific device. The Wood Library Museum says: “In 1854, manufacturer W.H. Burnap produced a well-known electrotherapy device that was purchased by the general consumer as well as some physicians and hospitals: The Davis & Kidder Patent Magneto-Electric Machine for Nervous Diseases.

“The operator of this electromagnetic generator would place handles in the patient’s hands or elsewhere on the patient’s body and then turn a crank to deliver a ‘mild’ alternating current to the patient. The force of the current depended upon the speed with which the crank was turned.

“The makers claimed that it could relieve pain, as well as cure numerous diseases, including cancer, consumption (tuberculosis), diabetes, gangrene, heart disease, lockjaw (tetanus), and spinal deformities.”

One more thing. No Double Turn? What’s that supposed to mean? I saw several of these signs downtown.

I think I figured it out. No left turns except from the left lane. Denver is the only place I’ve ever seen such a sign.