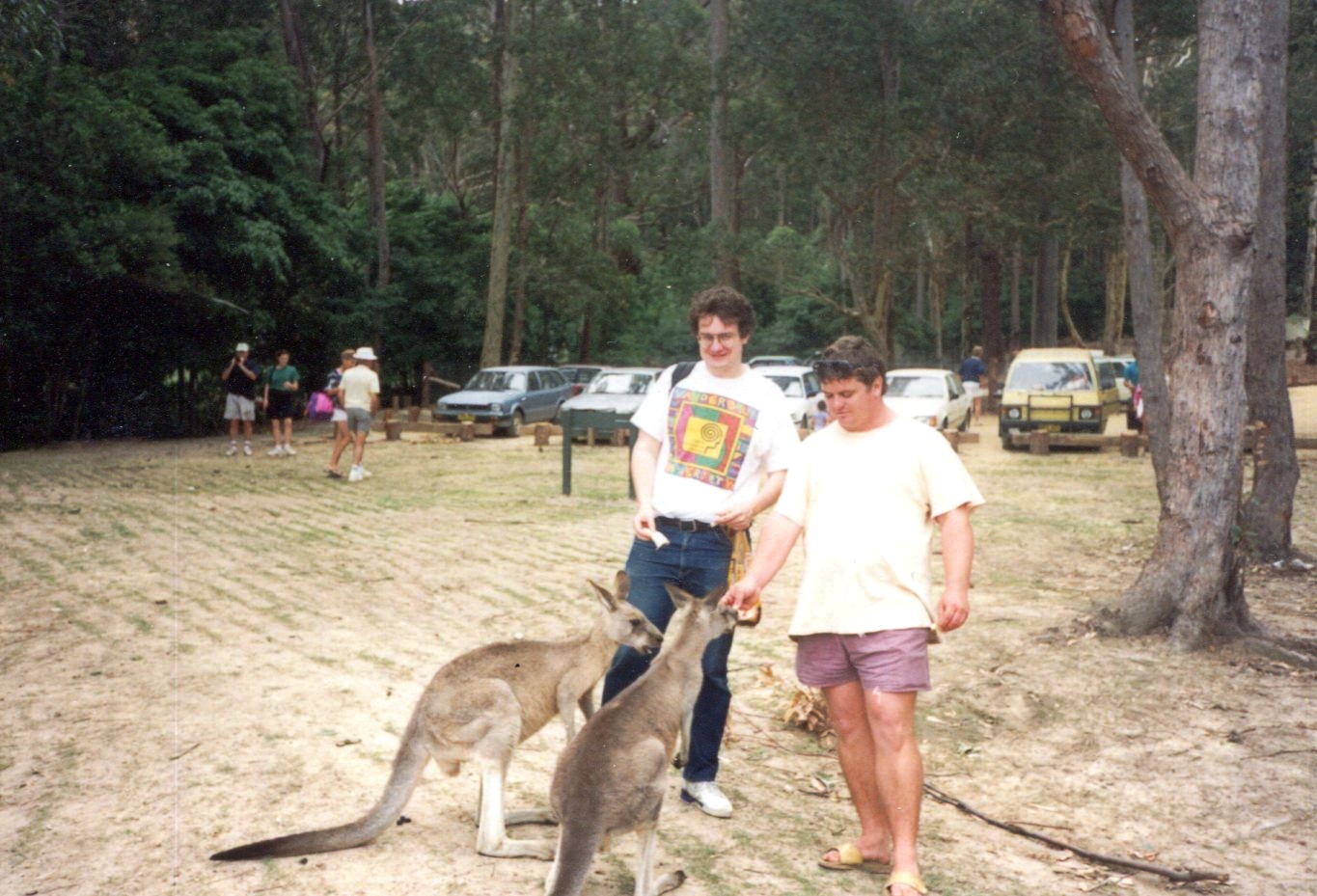

Australia Day has come around again, but it doesn’t seem fitting to post pictures of me standing near wallabies in New South Wales or recalling how they call Rice Krispies Rice Bubbles in Oz or my Christmas Day walk around in Canberra in a T-shirt.

Seems like one damn thing after another for the Lucky Country this year. Some choice recent headlines:

“Australia’s Wild Weather: First Fires, Now Baseball-Size Hail” — New York Times, Jan. 20

“Australia Rains Bring Relief From Fires — and a Surge in Deadly Spiders” — Smithsonian, Jan. 24

“Coronavirus: first Australian case confirmed in Victoria as five people tested in NSW” — The Guardian, Jan. 24

“Record 81 days of bad air quality in Sydney” — Sydney Morning Herald, Jan. 24.

Curious, I took a look at the web site of NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System, which (as it says) “distributes Near Real-Time (NRT) active fire data within 3 hours of satellite observation from both the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS).”

Took a screenshot of the Fire Map of Australia on the site as it appeared on Friday. Fires in the previous 24 hours, it says.

I can see why the air is bad in Sydney and why parts of Canberra — which is a small city practically plopped down in the bush — have been evacuated.

I can see why the air is bad in Sydney and why parts of Canberra — which is a small city practically plopped down in the bush — have been evacuated.

Still, I’m not sure the map helps me grasp the magnitude of the bush fires. Maybe that’s not really possible. I wondered about that even more when I looked at Africa at the same time.

Looks like central Africa is burning to a crisp. But do the many points of fire denote blazes regardless of size? That way a lot of small fires — which could be entirely normal for central Africa right now — wouldn’t be a catastrophe on the order of a smaller number of much larger fires in Australia.

Looks like central Africa is burning to a crisp. But do the many points of fire denote blazes regardless of size? That way a lot of small fires — which could be entirely normal for central Africa right now — wouldn’t be a catastrophe on the order of a smaller number of much larger fires in Australia.

Another NASA page hints at an answer. First, it says, “The colors are based on a count of the number (not size) of fires observed within a 1,000-square-kilometer area.” Also: “Across Africa, a band of widespread agricultural burning sweeps north to south over the continent as the dry season progresses each year.”

I’ve changed my mind. I think I will post a picture of wallabies. In hopes that better times are ahead for Australia.

December 1991: We’re feeding wallabies at Pebbly Beach on the NSW coast, which was damaged by fire recently, according to local reports. The other fellow is Peter, a friend I stayed with for a while in Canberra. Lost touch with him long ago; hope he’s well.