Oklahoma isn’t known as much of a nanny state. So in retrospect it’s no surprise that the U.S. 271 entrance to Talimena National Scenic Byway, which is a two-lane road through the Winding Stair National Recreation Area, was wide open on April 16, a gloomy, drizzly day with the mountains shrouded in clouds.

Some other jurisdiction might have put up barricades to protect drivers from their own foolish impulse to drive the road no matter what, but Oklahoma doesn’t roll that way.

Besides, the facility at the entrance was abandoned. I did see signs for a recreation area headquarters in the nearest town, Talihina, so I supposed the rangers or rangers-equivalent moved there.

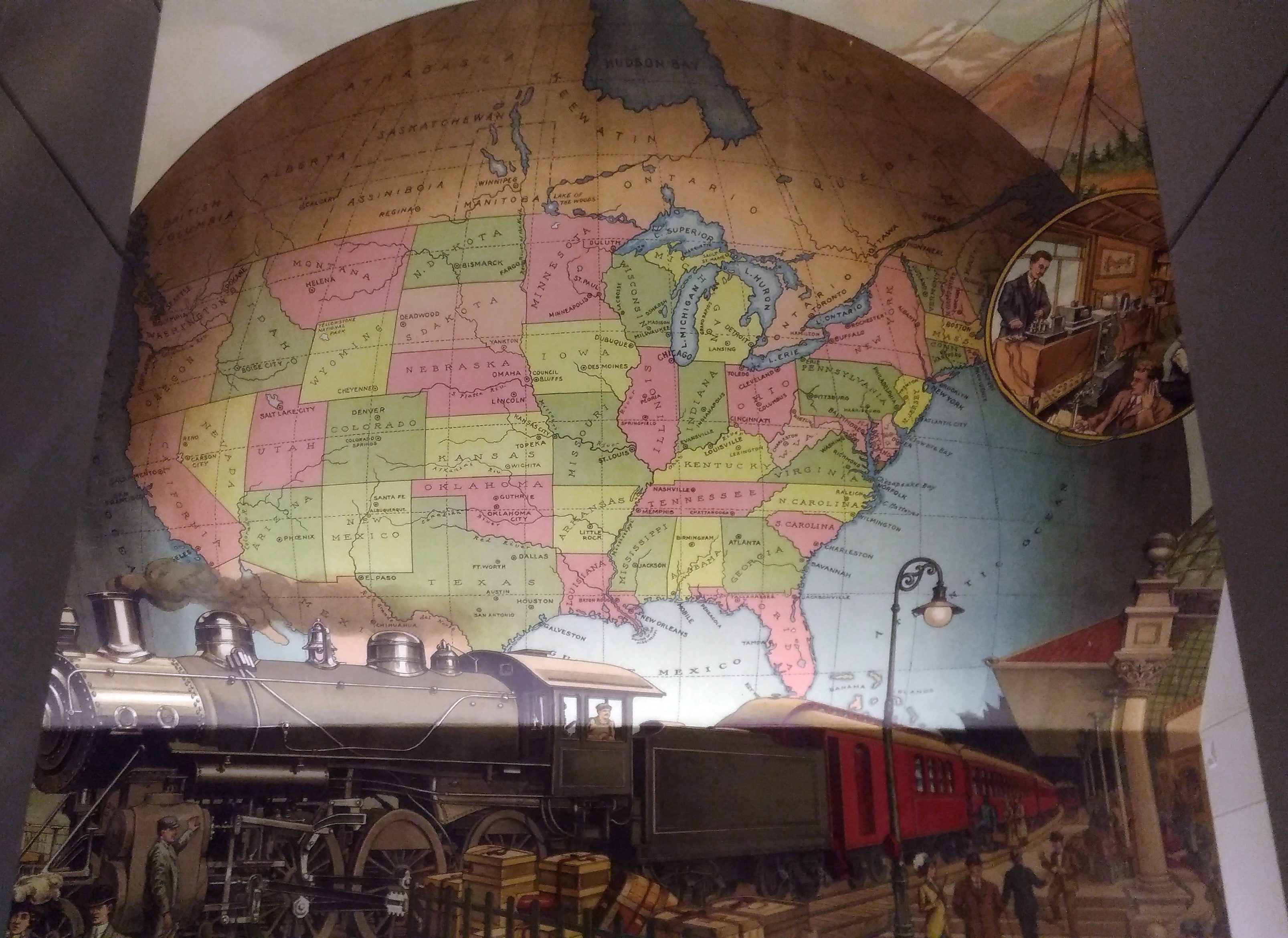

I was eager to drive the byway for two reasons. One, it’s a national scenic byway. In my experience, that generally means some good driving on the offing. Some car-commercial driving.

Also, the poetry of that name: Winding Stair Mountains. Even if they really are fairly small mountains, that’s a name and a place on the map that has intrigued me for a long time.

I stopped at an historic marker a short ways from the entrance that told me that the Ft. Smith-Ft. Towson Military Road once crossed the Winding Stair Mountains at that point, but it wasn’t the basis of the modern road, part of Oklahoma State Highway 1, which was completed only in 1969. I took a short walk in the nearby forest. The road also traverses a western section of Ouachita National Forest.

Then I took a look at the road ahead.

I wasn’t discouraged. I figured there might be patches of fog to drive through. Also, I’d seen two cars enter the road ahead of me.

The first few miles were gorgeous indeed, with places to stop that looked like this.

Pretty soon, though, the fog turned thick. I took it slow, about 30 mph, but even so the hazard of the drive was top of mind. I could see maybe 10 feet ahead, on a road that wound around and climbed and dropped — with steep drops into ditches sometimes off one or the other shoulder.

Mostly, I knew that if something appeared in the road ahead of me, such as an animal or worse, a stopped car, I might easily hit it. I don’t think I was risking death or even injury myself that much, just highly inconvenient damage to my car and maybe legal problems.

Now the views off to the side of the pullouts in the road looked more like this.

Yet the way — only about 12 miles on the section I wanted to drive — wasn’t entirely foggy. Sometimes I’d see the fog thin out ahead of me, suddenly, and even more suddenly, clear away completely. The beauty of the surroundings was suddenly clear as well, passing through a contoured forest of wet pine, oak, flowering dogwood and more.

As it happened, I encountered no one else on the road during my drive, neither cars nor motorcycles nor deer, and then headed north on U.S. 59. Take that route and before long you pass through Heavener, Oklahoma, where you see signs for Heavener Runestone Park. Or, and I think not all of the signs have been changed, Heavener Runestone State Park. Even the likes of Atlas Obscura still calls it a state park.

The place hasn’t been a state park for 10 years. Supposedly recession-era budget cuts are to blame, but I suspect that the park had embarrassed the state long enough, maybe since its founding in 1970.

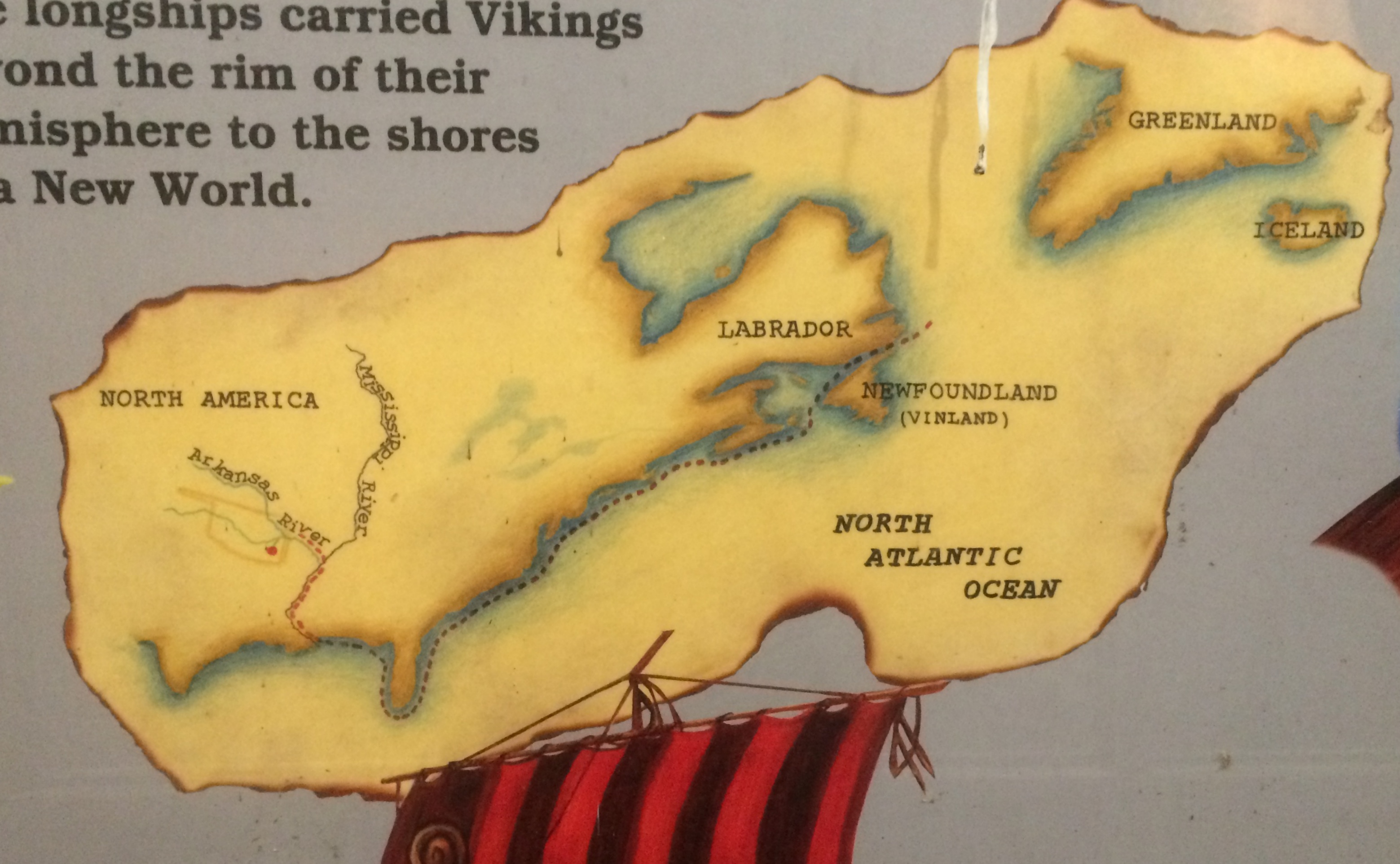

At some point in the past, someone carved runes into a sandstone boulder near Heavener. A local woman, one Gloria Farley, did her own research in the 1950s and determined that Norsemen had shown up in the future Oklahoma during the golden age of Vikings getting around (ca. 1,000 years ago), carved the runes, and then went on their way. Without leaving any other trace.

Apparently Gloria had friends in state government, and so 55 acres were made into a state park, its centerpiece being the rock, with a shelter built to protect it from the elements and vandals.

The boulder and its runes are behind glass inside.

Signs near the glass case carry on the fantasy that Vikings visited Oklahoma.

These days the park belongs to the town of Heavener and is overseen by a nonprofit. I did my little bit to support it, since there is no admission, by buying some postcards in the shop. (Also to support the manufacture of postcards in general.)

I don’t care that the place was founded on a fairly obvious hoax, maybe done by an Scandinavian immigrant in the 19th century with a peculiar sense of humor. In fact, that makes it more interesting, just as the faux Lincoln family log cabin does the Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park.

Besides, the loop to and from the Heavener Runestone, a path along the side of Poteau Mountain, is a good walk, even if wet with recent rain when I was there.

It’ll never be a World Heritage Site, unless some wickedly serious paradigm shift happens, but even so the non-state park preserves, in a pleasant green spot, an eccentric vision.