Nearly two years ago, media distribution company Orchard Enterprises provided 21 songs to YouTube, cuts on a collection called Uncle Walt’s Band Anthology. Subtitled — and it really captures the essence of that band — “Those Boys From Carolina, They Sure Enough Could Sing…”

Sure enough. The three-man band, Walter Hyatt, Champ Hood and David Ball, all originally from Spartanburg, SC, existed for a few years in the early 1970s and again in the late ’70s and early ’80s. They produced four original albums, did solo work, and played with a good number of other musicians in Austin and Nashville over the years. Those few reviews one can find about Uncle Walt’s Band tend to characterize them as Americana, and I supposed they were — a mix of American styles by South Carolina musicians who honed their skills in Nashville and Austin both.

Though fondly remembered by a few, especially other musicians, wider fame eluded Uncle Walt’s Band. I already knew that, but the point is hammered home by looking at the view count for some of their wonderful songs on Anthology — such as the fun “Seat of Logic” (only 533 views after two years, not 533,000 as by rights it ought to be); the winsome “Ruby” (only 569 views); and the sweetly melancholic “High Hill” (only 344 views); and on and on.

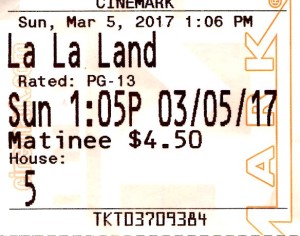

Forty years ago this evening I had the exceptionally good fortune of seeing Uncle Walt’s Band live in Nashville. “Crystalline sound,” I wrote in the diary I kept at the time, along with other unhelpful scraps when it comes to remembering it now. Still, the show was some of the best live music I saw in college, or ever really. A less fanciful way to characterize the gentlemen who played for us that evening would be near-perfect three-voice close harmony, with guitar, fiddle and bass.

I had taken a month-long trip not long before that evening, returning to Nashville less than a week earlier, with plans to attend summer school, but not take it all that seriously. That is exactly what I did and I don’t regret a moment of it. While I was away, my friend Dan had obtained the records Uncle Walt’s Band (a renaming and reissue of the 1974 Blame It On The Bossanova) and An American in Texas (1980, the same year the band appeared on Austin City Limits).

To put it in music biz terms, those records were in heavy rotation around the house where Dan and Rich lived, and where Mike, Steve and I were constant visitors that summer. As soon as I returned to Nashville, I heard it too. Then we got wind of the fact that Uncle Walt’s Band was playing live on Saturday the 12th at a place called The Sutler. We couldn’t believe our luck, and we weren’t about to miss that.

At time I called The Sutler “a tavern next to a bowling alley, a bakery and a restaurant,” which it was, though I didn’t record its address on 8th Ave. South in the Melrose neighborhood. That was further than we usually went, though (I know now), not that far from campus. Dive might not quite have been the word for the place, but it certainly wasn’t posh, and while I’m pretty sure I went there a few times in later years, I only remember seeing UWB there, and the joint’s last iteration closed only this year. It was standing room only for a while, but eventually we got a table. We stayed for the whole show. My mind’s eye can visualize it even now, and my mind’s ear can hear a crystalline echo of their sound.

UWB broke up for the last time the year after we saw them, but their musical presence that summer made an impression on me. Enough that in the late ’80s, when I was visiting Austin, I noticed a small poster somewhere advertising a show by Walter Hyatt at the famed Waterloo Ice House on on Congress Ave. We have to go to that, I told Tom Jones, whom I was visiting, and so we did.

During one of the breaks in that show, I asked Hyatt where I could buy copies of the two records that I remembered so fondly from the summer of ’82 — I think I even mentioned the show at The Sutler — since finding obscure music was more of a chore in those days. He gave me an address to send a check to, and soon after I did, I received an audio cassette of Uncle Walt’s Band and An American in Texas, which I listened to periodically over the years and own to this day.

Forty years is a long time, and time has taken its toll. Walter Hyatt died in the ValuJet Flight 592 crash in 1996 and Champ Hood died of cancer in 2001. David Ball has had a successful career as a country musician and is now pushing 70.

One more thing: I didn’t realize until the other day that the subtitle, “Those Boys From Carolina…” was no random pick. Lyle Lovett, Texan of distinct hair and winning ways with song, mentioned UWB in a song he recorded long after the band was gone, but before Walter Hyatt died, the amusing “That’s Right, You’re Not From Texas.”

Those boys from Carolina,

They sure enough could sing.

But when they came on down to Texas,

We all showed them how to swing.