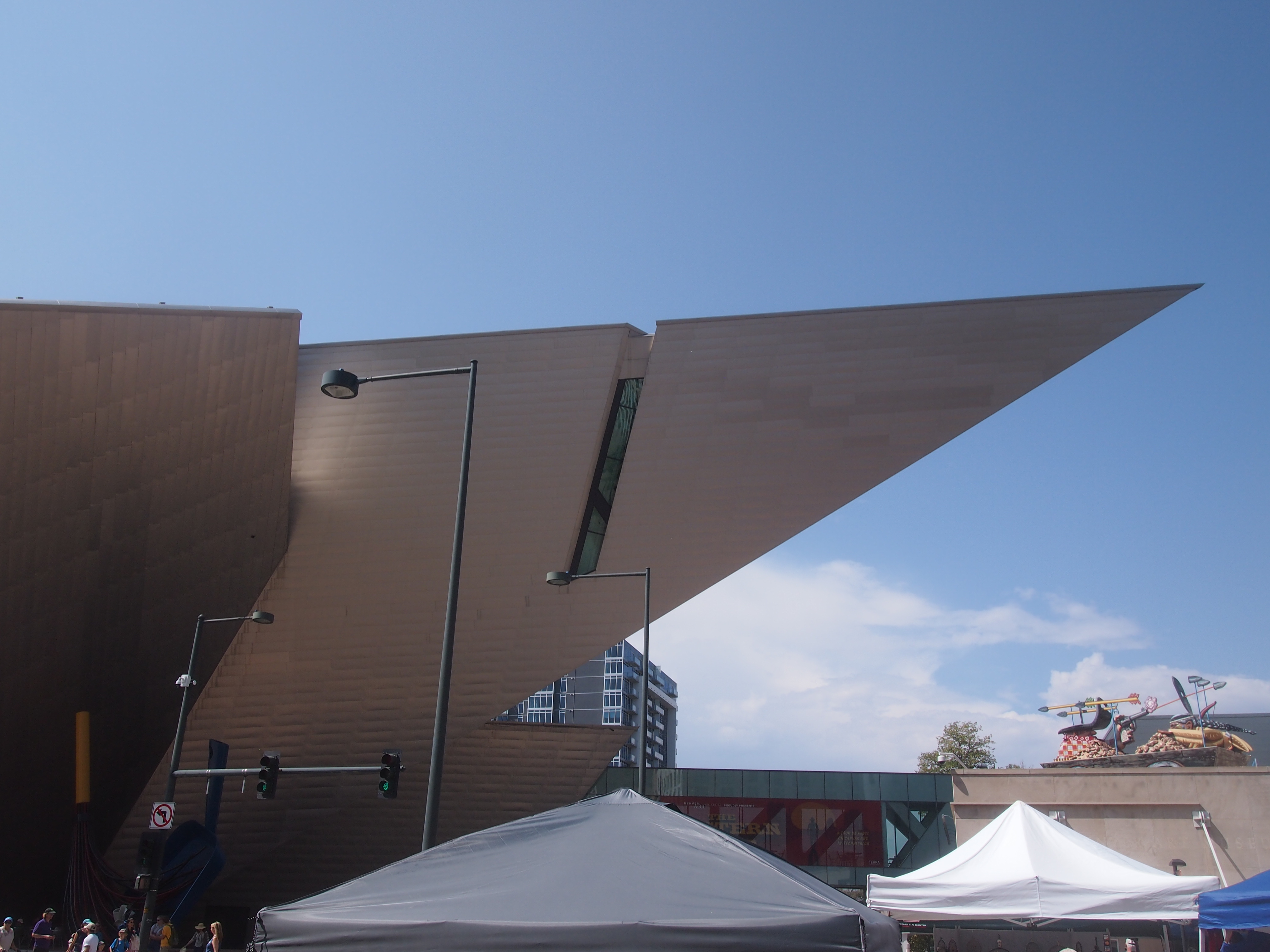

At first, approaching from some blocks away, I didn’t realize this was one of the main buildings of the Denver Art Museum, which I visited on the afternoon of September 9.

I spent some time looking at it, though, because it isn’t like anything else in the area. I had a thought that shows my age: crumpled punch card.

I spent some time looking at it, though, because it isn’t like anything else in the area. I had a thought that shows my age: crumpled punch card.

If I ever asked my daughters, or one of their contemporaries, what’s a punch card? the answer I would surely get is, I don’t know. But I remember seeing them as late as the early ’80s. Do not fold, spindle or mutilate.

The building, known as the museum’s North Building, is from the age of punch cards, completed in 1971 and one of the last works of architect Gio Ponti. Modernist Ponti’s work is otherwise unrepresented in North America and, having never been to Milan (or made any systematic study of the built environment), I had only a meager notion of his work.

There’s a helpful exhibit in the museum about the early history of the organization and the construction of the North Building, and then the development of the much newer Hamilton Building, completed only in 2006. That building is so horizontal that an image was hard to capture in one go, unless you step back further than I cared to.

If the North Building is Modernist, the Hamilton is Postmodernist? I suppose. Odd geometry for the sake of odd geometry by starchitect Daniel Libeskind. Interesting to look at, certainly. Like the Ascent at Roebling’s Bridge in greater Cincinnati, unfinished the last time I was in that town.

If the North Building is Modernist, the Hamilton is Postmodernist? I suppose. Odd geometry for the sake of odd geometry by starchitect Daniel Libeskind. Interesting to look at, certainly. Like the Ascent at Roebling’s Bridge in greater Cincinnati, unfinished the last time I was in that town.

As any art museum of any size should — and it’s credited with being the largest art museum between Chicago and the West Coast — DAM has a wealth of works on display, and no doubt a sizable inventory in storage. Too much for any one visit: European and American art of earlier centuries, Asian works, Pre-Columbian items and a Spanish Colonial collection, modern African and Oceanic pieces, photography, textiles and more.

I’d read that one of DAM’s specialties was American Indian art, and so it is. Like the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, the collection includes Indian art and artifacts of historic interest, but also artwork by 20th- and 21st-century Native Americans.

I spent a fairly long time in these galleries, beginning with earlier items, such as this room, which naturally reminded me of the the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology.

Except for this work, “Blanket Story: Confluence, Heirloom, and Tenth Mountain Division” by Marie Watt, 2013.

Which is composed of a very tall stack of blankets, “donated mostly by members of the local community,” said the plaque, which I take to mean the Seneca, since Watt belongs to that tribe. I asked a docent how the stack was held up; she said the artist and the curator probably knew, but she didn’t. There was no visible means of support.

Another room sports various vessels, in this case the works of Zia artists in New Mexico.

Moving forward in time, “Sacro-Wi” by Oscar Howe, 1967.

Moving forward in time, “Sacro-Wi” by Oscar Howe, 1967.

He sounded familiar. Turns out he’s the same artist who did the interior murals at the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota.

He sounded familiar. Turns out he’s the same artist who did the interior murals at the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota.

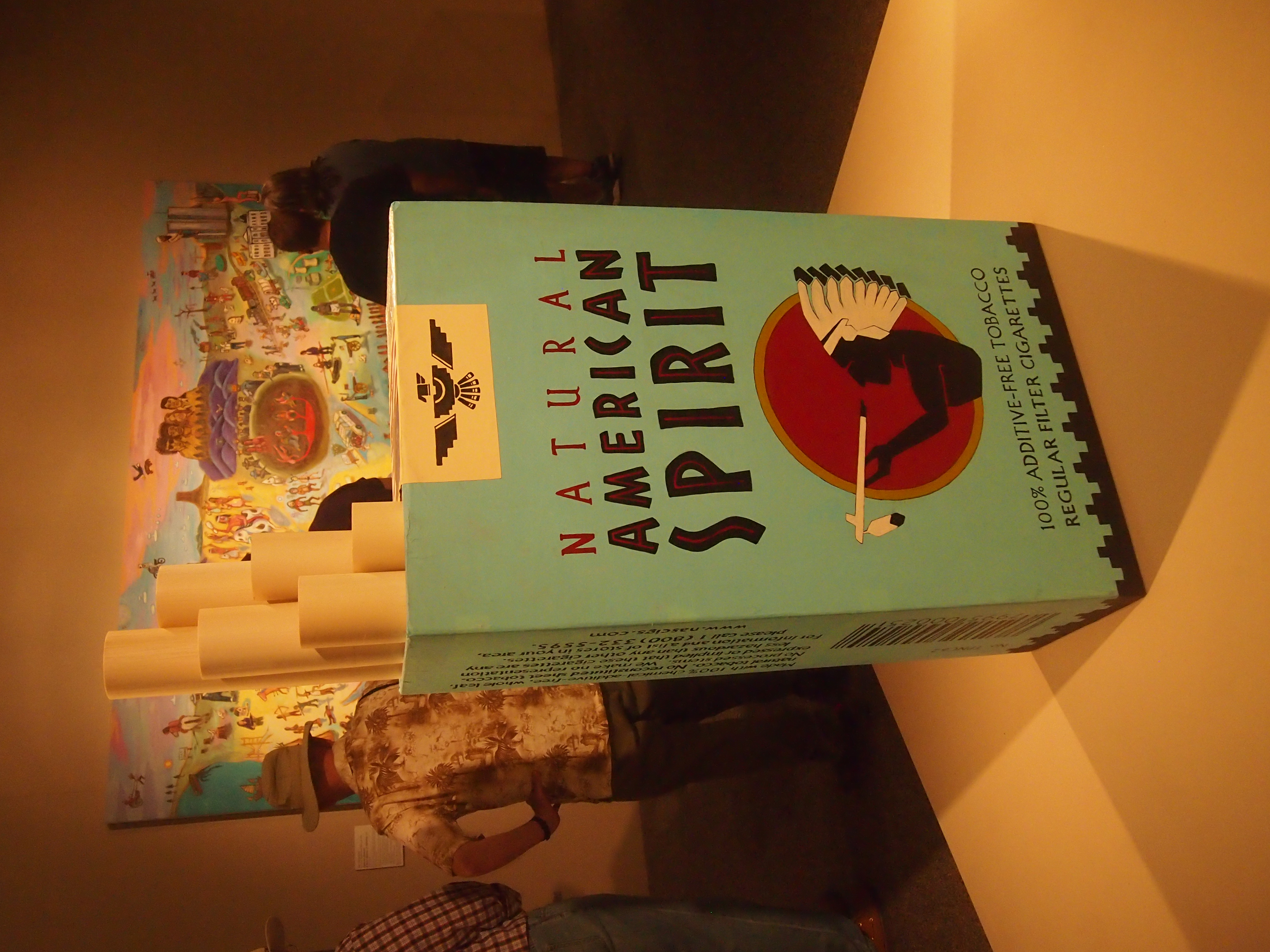

Closer to our time, some parody: “American Spirit,” by David P. Bradley, 2004-05.

And “Land O Bucks, Land O Fakes, Land O Lakes,” by the same artist, 2006. Reminded me very much of Wacky Packages, which were all the rage when I was in junior high.

And “Land O Bucks, Land O Fakes, Land O Lakes,” by the same artist, 2006. Reminded me very much of Wacky Packages, which were all the rage when I was in junior high.

As interesting as the works were, American Indian art was hardly the full extent of DAM. I also spent a while looking at European art from earlier centuries.

As interesting as the works were, American Indian art was hardly the full extent of DAM. I also spent a while looking at European art from earlier centuries.

Note the chairs. The older I get, the more I appreciate museums with seating with backs.

Note the chairs. The older I get, the more I appreciate museums with seating with backs.

A detail from a striking painting in that room, “La Famille du Saltimbanque: L’Enfant Blessé (The Family of Street Acrobats: The Injured Child),” by Gustave Doré, ca. 1873.

One of the other things he did was wood-engraved illustrations for “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

And now for something completely different: a detail from “Thomas Sheppard,” by Andrea Soldi, 1773.

Something even more different: a Chinese bamboo carving.

Something even more different: a Chinese bamboo carving.

By that time I saw that I’d wandered off into a gallery dedicated to a collection of East Asian bamboo carvings of considerable variety and virtuosity. I must have seen such things while in East Asia, but time passes, and you forget.

By that time I saw that I’d wandered off into a gallery dedicated to a collection of East Asian bamboo carvings of considerable variety and virtuosity. I must have seen such things while in East Asia, but time passes, and you forget.

Among other things, writings about bamboo were also posted in the room. Such as a poem attributed to Su Shi, a Chinese poet, calligrapher and gastronome (1037-1101) of the Song dynasty, translated by Jan Walls. (How come I don’t remember this statue of Su Shi near the West Lake? I must have seen it.)

At a Reclusive Monk’s Green Bamboo Studio

I would rather eat a meal without meat

than live in a place without bamboo.

Eating without meat makes you lose weight,

but living without bamboo makes you lose refinement.

When a person loses weight, it may be regained,

but when scholars lose refinement they are untreatable.

Others will find these words funny,

seeming lofty and at the same time, crazy.

Ruminate on this carefully if you are wise,

or you will never ride a crane to Paradise.