Not far from downtown Birmingham is Sloss Furnaces, site of pig iron production from 1882 to 1971.

In our time, Sloss is an enormous forest of iron and steel, besides being a National Historic Landmark, sometime music venue, and site of a metal arts program. The long shed was, in fact, active with metal working while we visited. To see the main part of the site, you walk past the shed through a kind of tunnel.

In our time, Sloss is an enormous forest of iron and steel, besides being a National Historic Landmark, sometime music venue, and site of a metal arts program. The long shed was, in fact, active with metal working while we visited. To see the main part of the site, you walk past the shed through a kind of tunnel.

“In 1871 Southern entrepreneurs founded a new city called Birmingham and began the systematic exploitation of its minerals,” the Sloss Furances web site says. It’s an excellent short history — you don’t always get that at web sites — so I will quote at at length, to go with some pictures.

“In 1871 Southern entrepreneurs founded a new city called Birmingham and began the systematic exploitation of its minerals,” the Sloss Furances web site says. It’s an excellent short history — you don’t always get that at web sites — so I will quote at at length, to go with some pictures.

“One of these men was Colonel James Withers Sloss, a north Alabama merchant and railroad man. Colonel Sloss played an important role in the founding of the city by convincing the L&N Railroad to capitalize completion of the South and North rail line through Jones Valley, the site of the new town.

“In 1880, having helped form the Pratt Coke and Coal Co., which mined and sold Birmingham’s first high-grade coking coal, he founded the Sloss Furnace Co., and two years later ‘blew-in’ the second blast furnace in Birmingham.”

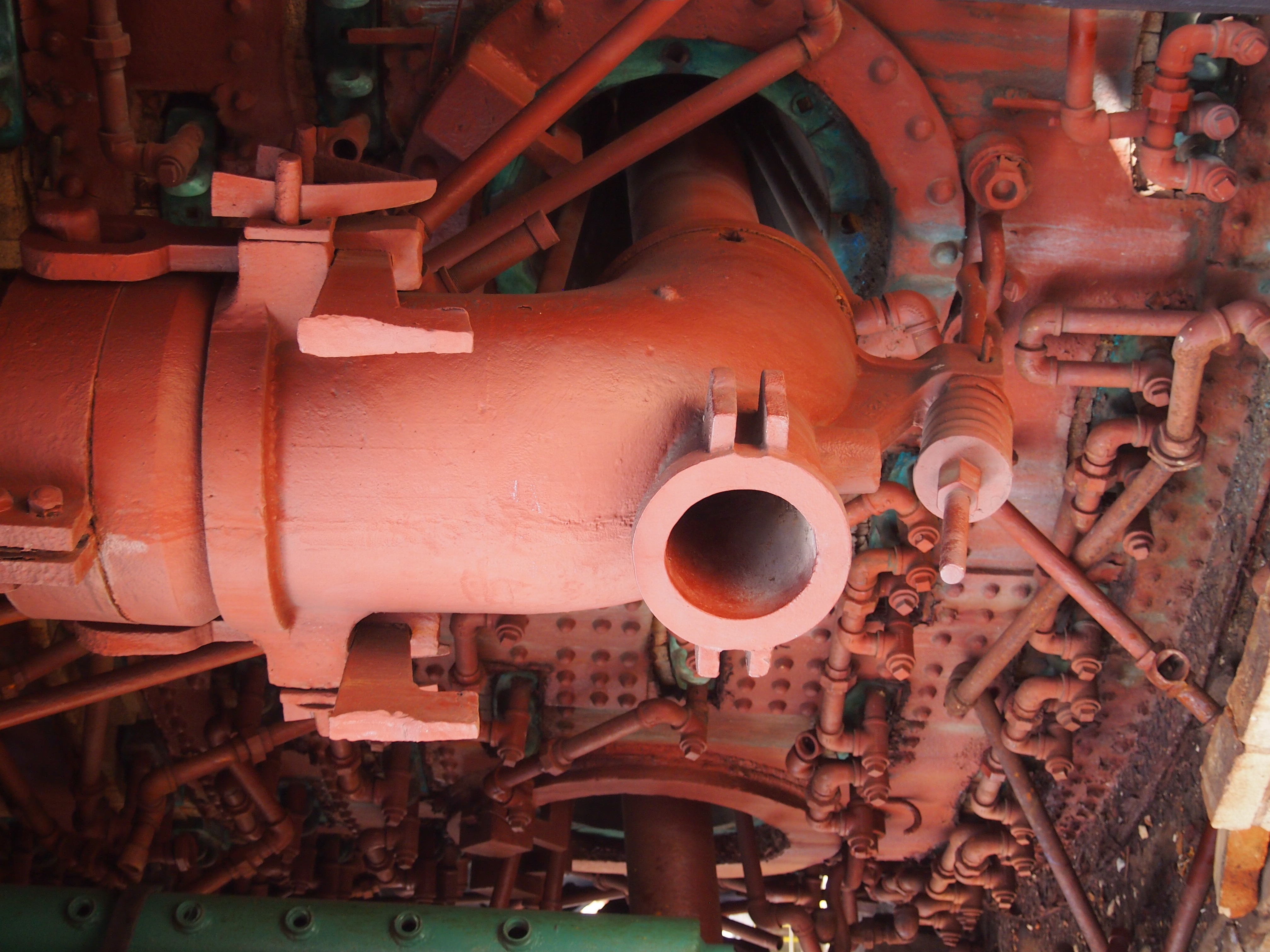

The site these days includes relics towering into the sky.

And entrances into dark cavities.

And entrances into dark cavities.

“Construction of Sloss’s new furnace (City Furnaces) began in June 1881, when ground was broken on a fifty-acre site that had been donated by the Elyton Land Co. Sixty feet high and eighteen feet in diameter, Sloss’s new Whitwell stoves were the first of their type ever built in Birmingham and were comparable to similar equipment used in the North.

“Construction of Sloss’s new furnace (City Furnaces) began in June 1881, when ground was broken on a fifty-acre site that had been donated by the Elyton Land Co. Sixty feet high and eighteen feet in diameter, Sloss’s new Whitwell stoves were the first of their type ever built in Birmingham and were comparable to similar equipment used in the North.

“Local observers were proud that much of the machinery used by Sloss’s new furnaces would be of Southern manufacture. It included two blowing engines and ten boilers, thirty feet long and forty-six inches in diameter. In April 1882, the furnaces went into blast. After its first year of operations, the furnace had sold 24,000 tons of iron. At the 1883 Louisville Exposition, the company won a bronze medal for ‘best pig iron.’ ”

“Nothing remains of the original furnace complex. The oldest building on the site dates from 1902 and houses the eight steam-driven ‘blowing-engines’ used to provide air for combustion in the furnaces. The engines themselves date from the period 1900-1902 and are a unique and important collection — engines such as these powered America’s Industrial Revolution. The boilers, installed in 1906 and 1914, produced steam for the site until it closed in 1971.

“Between 1927 and 1931 the plant underwent a concentrated program of mechanization. Most of its major operation equipment — the blast furnaces and the charging and casting machinery — was replaced at this time. In 1927-28, the two furnaces were rebuilt, enlarged, and refitted with mechanical charging equipment, doubling the plant’s production capacity. While the site strongly reflects the changes made from 1927-1931, some of the technology is more current.”

“Despite being dominated by black labor, the industrial workplace was rigidly segregated until the 1960s. Workers at Sloss bathed in separate bath houses, punched separate time clocks, attended separate company picnics. More important was the segregation of jobs.

“Despite being dominated by black labor, the industrial workplace was rigidly segregated until the 1960s. Workers at Sloss bathed in separate bath houses, punched separate time clocks, attended separate company picnics. More important was the segregation of jobs.

“The company operated as a hierarchy. At the top there was an all white group of managers, chemists, accountants, and engineers; at the bottom an all black ‘labor gang’ assisted (until its demise in 1928) by the use of convict labor. Sloss utilized the convict leasing system only in its coal mines. As Lewis noted in Sloss Furnaces, ‘….convict labor, mostly black, was an important weapon in the district’s economic warfare with northern manufacturing.’ Slavery had not died but merely been transformed.”