About three and a half years ago, I took a brisk walk through Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, a hilly, wooded place featuring a vast array of headstones and funerary art. The very model of a Victorian rural cemetery, you might say, except that the city has grown around it. Also, it’s still an active cemetery in the 21st century.

I wanted to go back, especially since I spent the latter part of my recent trip to New York staying with my nephew Robert and his girlfriend Meredith at their apartment in Brooklyn, which happens to be two subway stops away from the main entrance of Green-Wood. Even better, I discovered that a tour — the Twilight Tour — ran from 6 to 8 p.m. on Friday, March 30, after my work obligations were over.

So I bought a ticket online, and showed up at the main gate not long before 6. The gate itself is a striking bit of Victorian Gothic Revival. Outside the entrance:

None other than Richard Upjohn, the same architect who did Trinity Church Wall Street, designed the gate. Looks like it, too. Inside the entrance:

None other than Richard Upjohn, the same architect who did Trinity Church Wall Street, designed the gate. Looks like it, too. Inside the entrance:

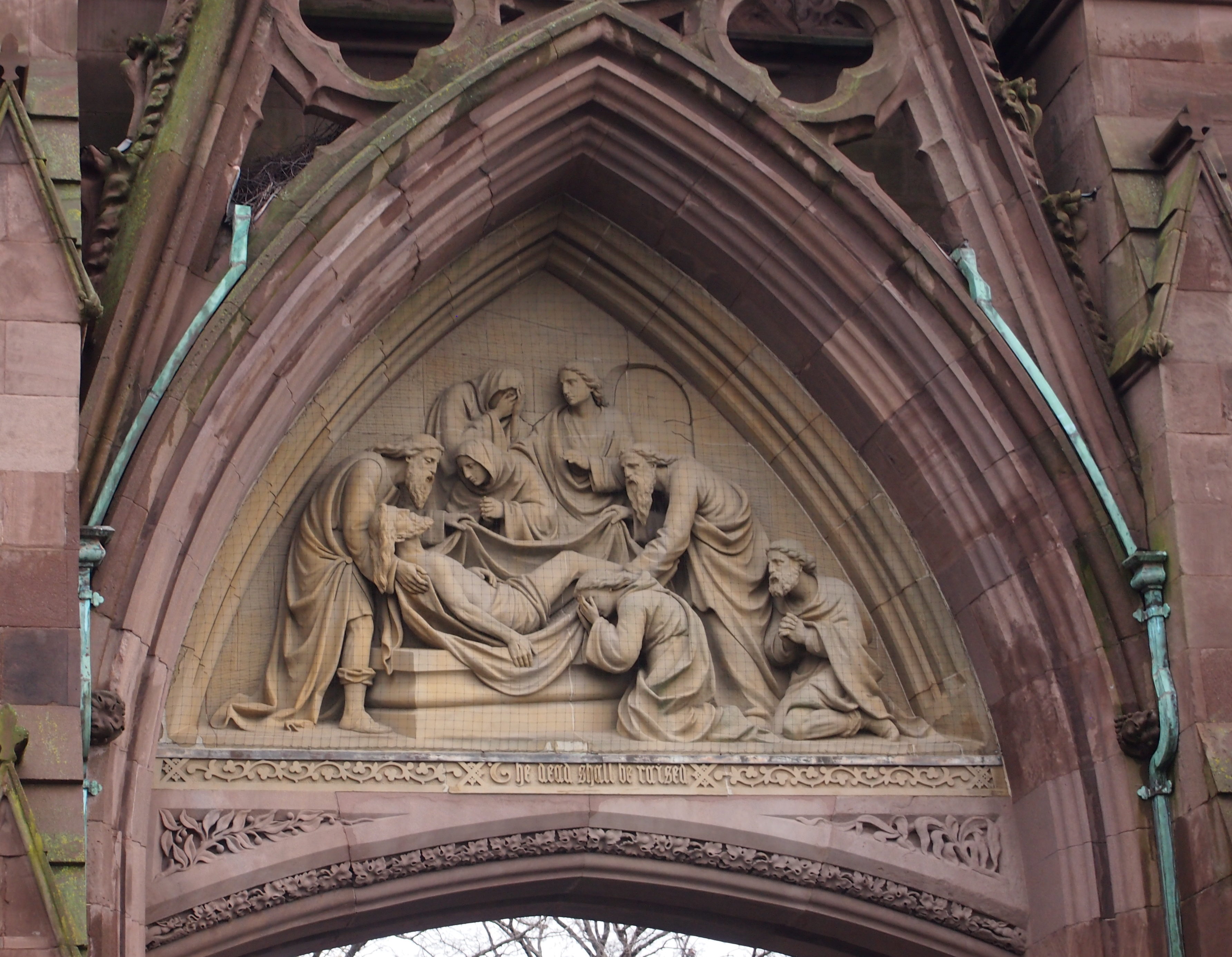

A resurrection-themed detail on the gate, one of four by John M. Moffitt.

A resurrection-themed detail on the gate, one of four by John M. Moffitt.

Gray clouds hung over the cemetery and there was occasional drizzle. But I was dressed for it, so that didn’t interfere with the pleasure of walking through Green-Wood again, into parts I didn’t go to last time, so vast is the cemetery.

Gray clouds hung over the cemetery and there was occasional drizzle. But I was dressed for it, so that didn’t interfere with the pleasure of walking through Green-Wood again, into parts I didn’t go to last time, so vast is the cemetery.

Even the bare trees and brown-green grass had their charms.

The tour wound up hills and down and around. I didn’t even bother trying to keep track of where we were. I just followed and listened to the guide, who knew a lot and pointed out things you might otherwise miss.

The tour wound up hills and down and around. I didn’t even bother trying to keep track of where we were. I just followed and listened to the guide, who knew a lot and pointed out things you might otherwise miss.

For instance, there aren’t that many Confederates in the cemetery, but there are a few. Such as Col. George Henry Sweet.

We soon came to the highest point in the cemetery, and in fact in Brooklyn, called Battle Hill for its part in a bloody episode in the Battle of Long Island (a.k.a. the Battle of Brooklyn) in the Revolution.

We soon came to the highest point in the cemetery, and in fact in Brooklyn, called Battle Hill for its part in a bloody episode in the Battle of Long Island (a.k.a. the Battle of Brooklyn) in the Revolution.

About 100 years ago, that event was memorialized on the hill by a sculpture called “Altar to Liberty: Minerva” by Frederick Ruckstull, which faces toward New York Harbor.

On a clear day, you can see the Statue of Liberty from Minerva’s perch, but we didn’t have a clear day. I understand that that particular the sightline is protected by law, like views of the capitol in Austin.

On a clear day, you can see the Statue of Liberty from Minerva’s perch, but we didn’t have a clear day. I understand that that particular the sightline is protected by law, like views of the capitol in Austin.

Also on Battle Hill is a sizable monument to New Yorkers who fought for the Union.

Not far away is the Van Ness-Parsons Egyptian Revival tomb. Pianist, teacher, organist and composer Albert Ross Parsons is interred there, among others.

Not far away is the Van Ness-Parsons Egyptian Revival tomb. Pianist, teacher, organist and composer Albert Ross Parsons is interred there, among others.

Clearly they wanted everyone to know that the tomb doesn’t evoke pagan Egypt, but rather Christian Egypt.

Clearly they wanted everyone to know that the tomb doesn’t evoke pagan Egypt, but rather Christian Egypt.

Soon we came to the grave of Leonard Bernstein.

Then the more elaborate memorial to Elias Howe, improver of the sewing machine and archenemy of Issac Singer.

Then the more elaborate memorial to Elias Howe, improver of the sewing machine and archenemy of Issac Singer.

As promised, the tour started to become a twilight tour after sunset. The last large tomb I had light enough to shoot was a doozy, though: Charlotte Canda.

As promised, the tour started to become a twilight tour after sunset. The last large tomb I had light enough to shoot was a doozy, though: Charlotte Canda.

I didn’t know the story of Charlotte Canda. The guide informed us. Charlotte, daughter of a wealthy New Yorker, died on her 17th birthday in a carriage accident in 1845. Her tomb is based on unused sketches she made herself a few months earlier, for an aunt of hers who had predeceased Miss Canda.

I didn’t know the story of Charlotte Canda. The guide informed us. Charlotte, daughter of a wealthy New Yorker, died on her 17th birthday in a carriage accident in 1845. Her tomb is based on unused sketches she made herself a few months earlier, for an aunt of hers who had predeceased Miss Canda.

Restoration efforts have been underway in recent years. According to the guide, back when Green-Wood was treated as a city park, Miss Canda’s tomb was an especially popular place to visit and picnic. The pathos of her story appealed to Victorians, I guess.

Restoration efforts have been underway in recent years. According to the guide, back when Green-Wood was treated as a city park, Miss Canda’s tomb was an especially popular place to visit and picnic. The pathos of her story appealed to Victorians, I guess.

We carried on in the near-dark, often using smartphone flashlights, and saw the remarkable gravestone of Cortland Hempstead, chief engineer of the steamship Lexington, which burned and sank in Long Island Sound in January 1840. Of the 143 souls aboard, only four are known to have survived. Hempstead wasn’t one of them.

As seen here, the stone includes a relief based on a Nathaniel Currier lithograph originally published in the New York Sun: “Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat ‘Lexington’ in Long Island Sound on Monday Eveg Jany 13th 1840, by Which Melancholy Occurrence Over 100 Persons Perished.”

We also saw Green-Wood’s catacombs, which are usually closed to the public. They aren’t remotely as extensive as the catacombs of Rome or Paris, but they were interesting: a long concrete tunnel dug into a hill with some dozens of chambers off to the sides, and people interred in the walls of the chambers. The place was dank and smelled like a cave. According to the guide, the catacombs were a more economic alternative than burial in a plot for a while in the 19th century, but they never really caught on, probably because water always made its way in.

After leaving the catacombs, we passed by the single grave at Green-Wood that I wanted to see more than any other: Boss Tweed. Not for the aesthetics of the marker — it’s large but fairly ordinary — but for making the passing acquaintance of such an infamous scoundrel, when he’s no longer in a position to pick one’s pocket.