Besides trees and a little public art and some brutalist buildings, here’s something else I saw at the University of Illinois at Chicago on Sunday, the likes of which I’d never seen before.

It’s a knife-sharpening cart, complete with cobble stones, on display on the second floor of Hull-House, with a sign that says: “Julio Fabrizio, an immigrant from Castelvino, Italy, to Chicago in 1919, built this knife-sharpening cart in the 1930s for his peddling services. Pushing it through the streets of his Near West Side neighborhood, Fabrizio used it to repair umbrellas and sharpen scissors, saws, and knives.”

It’s a knife-sharpening cart, complete with cobble stones, on display on the second floor of Hull-House, with a sign that says: “Julio Fabrizio, an immigrant from Castelvino, Italy, to Chicago in 1919, built this knife-sharpening cart in the 1930s for his peddling services. Pushing it through the streets of his Near West Side neighborhood, Fabrizio used it to repair umbrellas and sharpen scissors, saws, and knives.”

Since I was already at UIC on Sunday afternoon, I decided to drop by for a look at Hull-House, which is more formally called the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. All the years I’ve been in Chicago area, I’d never gotten around to it.

The current structure is a fragment of the 13-building complex in its heyday 100 years ago, but at least it’s a restored version of the original building, which dates back to 1856. By the time it became a settlement house in 1889, the house was fully part of the surrounding immigrant slum and so exactly where Addams and Hull-House cofounder Ellen Gates Starr wanted to be. The organization’s physical structure grew from there. The later buildings, just like much of the neighborhood, were destroyed in the 1960s to make way for the UIC campus.

“In the 1890s, Hull-House was located in the midst of a densely populated urban neighborhood peopled by Italian, Irish, German, Greek, Bohemian, and Russian and Polish Jewish immigrants,” the museum says.

“Jane Addams and the Hull-House residents provided kindergarten and day care facilities for the children of working mothers; an employment bureau; an art gallery; libraries; English and citizenship classes; and theater, music and art classes. As the complex expanded to include thirteen buildings, Hull-House supported more clubs and activities such as a Labor Museum, the Jane Club for single working girls, meeting places for trade union groups, and a wide array of cultural events.”

The museum is small but well designed to convey how the organization furthered the goals of the Progressive movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, besides providing numerous social services in the immediate neighborhood.

“Among the projects that they helped launch were the Immigrants’ Protective League, the Juvenile Protective Association, the first juvenile court in the nation, and a Juvenile Psychopathic Clinic (later called the Institute for Juvenile Research),” the museum notes.

“Through their efforts, the Illinois Legislature enacted protective legislation for women and children in 1893. With the creation of the Federal Children’s Bureau in 1912 and the passage of a federal child labor law in 1916, the Hull-House reformers saw their efforts expanded to the national level.”

Addams’ bedroom is part of the exhibit.

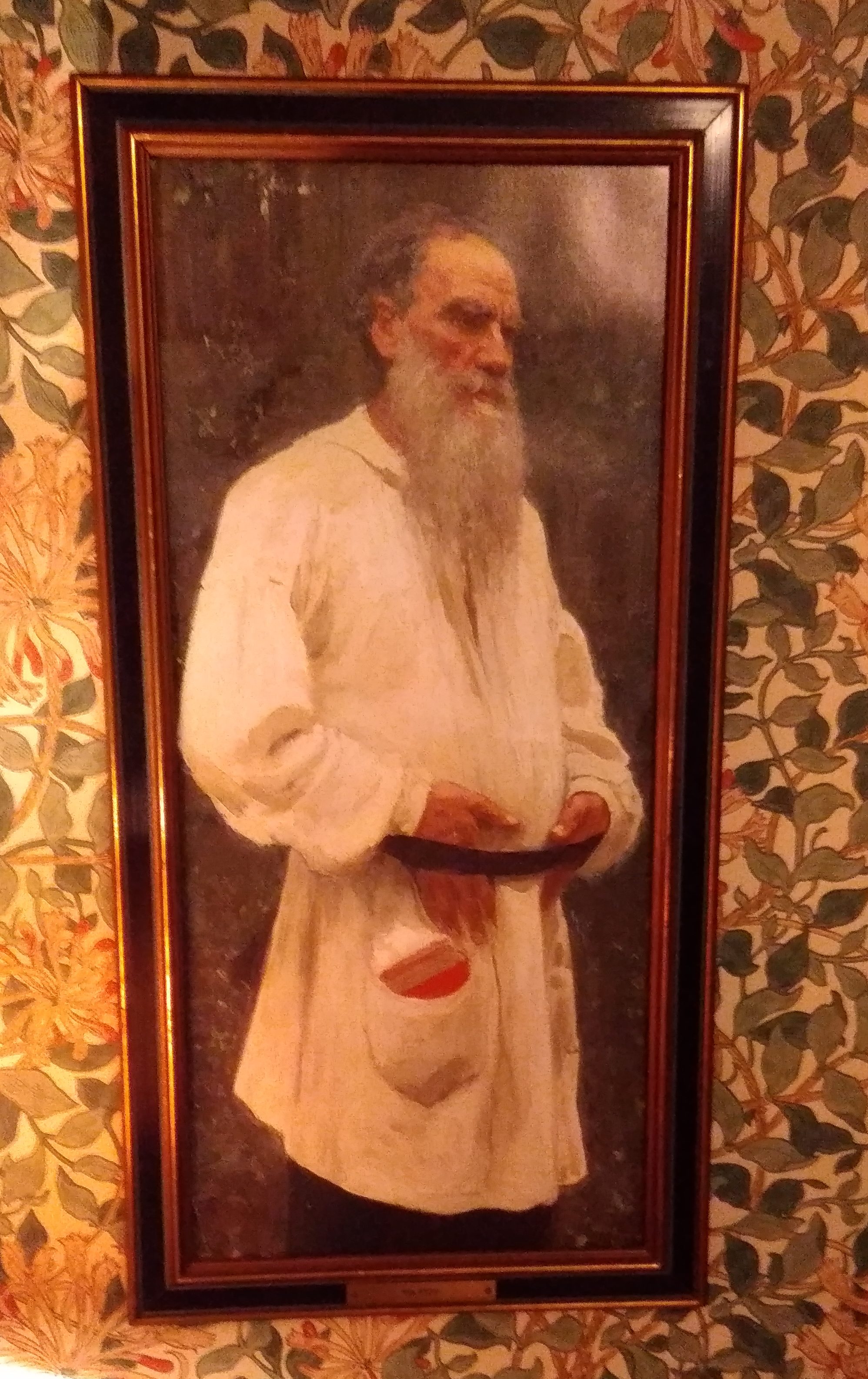

Fairly spare, though there’s a portrait of Tolstoy on the wall (no artist named that I could see, but it looks like a part copy of a 1901 portrait by Ilya Repin).

Fairly spare, though there’s a portrait of Tolstoy on the wall (no artist named that I could see, but it looks like a part copy of a 1901 portrait by Ilya Repin).

Apparently the Russian was an inspiration to Addams, though when they met in 1896 the event was less than comfortable for the American reformer.

Apparently the Russian was an inspiration to Addams, though when they met in 1896 the event was less than comfortable for the American reformer.

The museum isn’t all about Addams or even the other settlement workers. Other people associated with the organization are given their due. One in particular caught my eye: Morris Topchevsky (1899-1947), immigrant from Poland when it was still part of the Russian Empire, painter, etcher, lecturer, writer and red.

Some of his works are on display.

Topchevsky took classes at Hull-House and later taught there. Seems that he also spent time in Mexico in the 1920s, becoming friends with Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco, though too early to have hung out with Trotsky.