As historic sites go, Fort Smith National Historic Site is definitely worth a look, with its main building (former barracks-courthouse-jail), reconstructed gallows, site of a first fort, outline of the second fort’s former walls, parkland and walking paths, and a nice view of the Arkansas River.

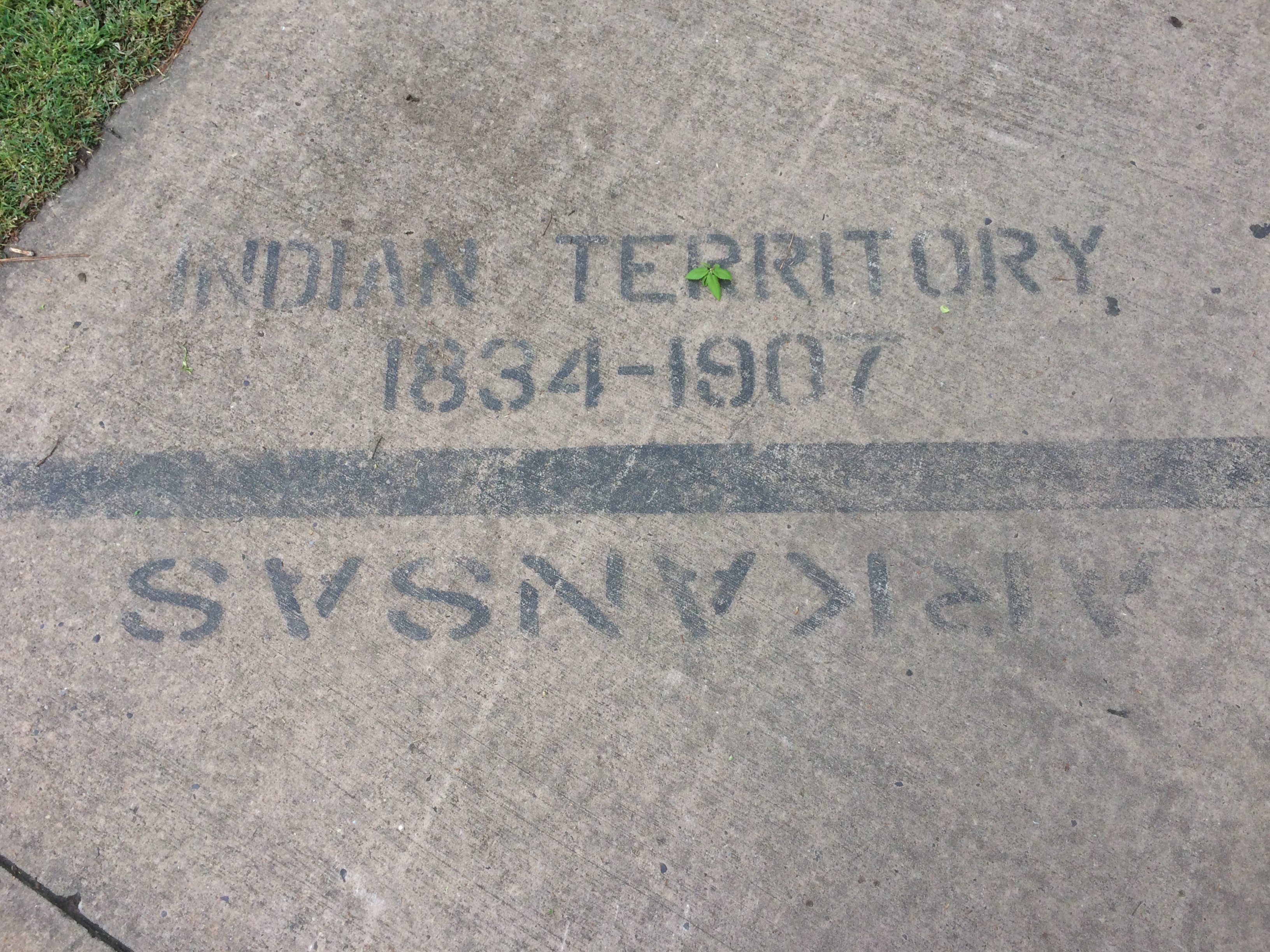

But what really caught my attention during my visit on April 17 was painted on one of the sidewalks.

“The line on the sidewalk behind you represents the 1834 boundary between Indian Territory and Arkansas,” the sign nearby simply says. “Indian Territory was defined as the unsettled land west of the Mississippi River not including states or previously organized territories.”

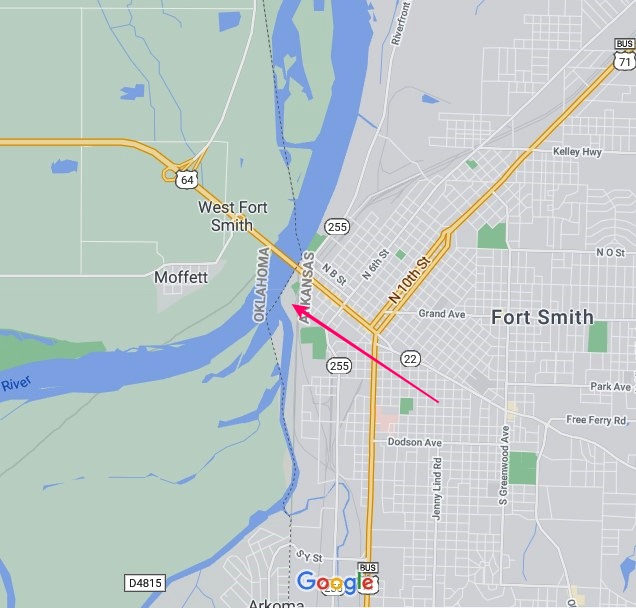

I should note that the line on the sidewalk isn’t the current border between Arkansas and Oklahoma. But it’s pretty close — at that point the line is on the eastern bank of the Arkansas River, at least according to Google Maps (not quite an infallible source).

The pink arrow points to about where the painted line is. As you can see, the modern border zags a bit to the west at that point, so that all of the land of the historic site — and the city of Fort Smith, for that matter — is in Arkansas.

At some point, that line must have been straight and a slice of land east of Arkansas-Poteau confluence was Indian Territory, if the sidewalk line is correct. This Encyclopedia of Arkansas article seems to deal with a border adjustment in the area, in the context of the Choctaw Nation-Arkansas border, which was the subject of decades of dispute.

But the article says the strip was “two miles wide and twelve miles long,” and the Fort Smith slice looks nowhere near that large, so I don’t know how the above border adjustment was made. Some Arkansas or Choctaw historian might, but I’m going to leave it at that.

The fort was originally established in 1817 to patrol the neighboring Indian Territory and named for the otherwise little-remembered Gen. Thomas Smith. The U.S. Army abandoned the first fort in 1824, but by that time a town had grown up near the fort. The Army built a second fort in 1838 that it occupied, except for a short Confederate period, until 1871.

The site of the first fort, entirely forgotten and not re-discovered until 1958.

During the Army period, the handsome main building of the second fort served as a barracks. Late in the 19th century, it was a federal courthouse and jail. Now it’s a museum. Closed when I visited, unfortunately.

Also handsome: the Historic Commissary Building. It too was closed.

Flat stones that mark where the second fort wall used to be. A sign pointed out that most later U.S. Army forts didn’t bother with walls.

Another prime attraction — maybe the prime attraction — is the rebuilt gallows.

“With the largest criminal jurisdiction of any federal court at the time, the Western District of Arkansas handled an extraordinary number of murder and rape cases,” a sign in front of the gallows says. “When a jury found defendants guilty in these capital cases, federal law mandated the death penalty. In Fort Smith, that meant an execution by hanging on a ‘crude and unsightly’ gallows.”

A separate sign lists everyone hanged at Fort Smith during the years (1873-96) that federal executions took place on the site, 87 men all together. The famed Judge Isaac C. Parker sentenced 160 people (156 men, four women) to death in that court, 79 of whom were eventually hanged. “George Maledon, known as the Prince of Hangmen, served as executioner at over half of the Fort Smith hangings,” the sign also noted.