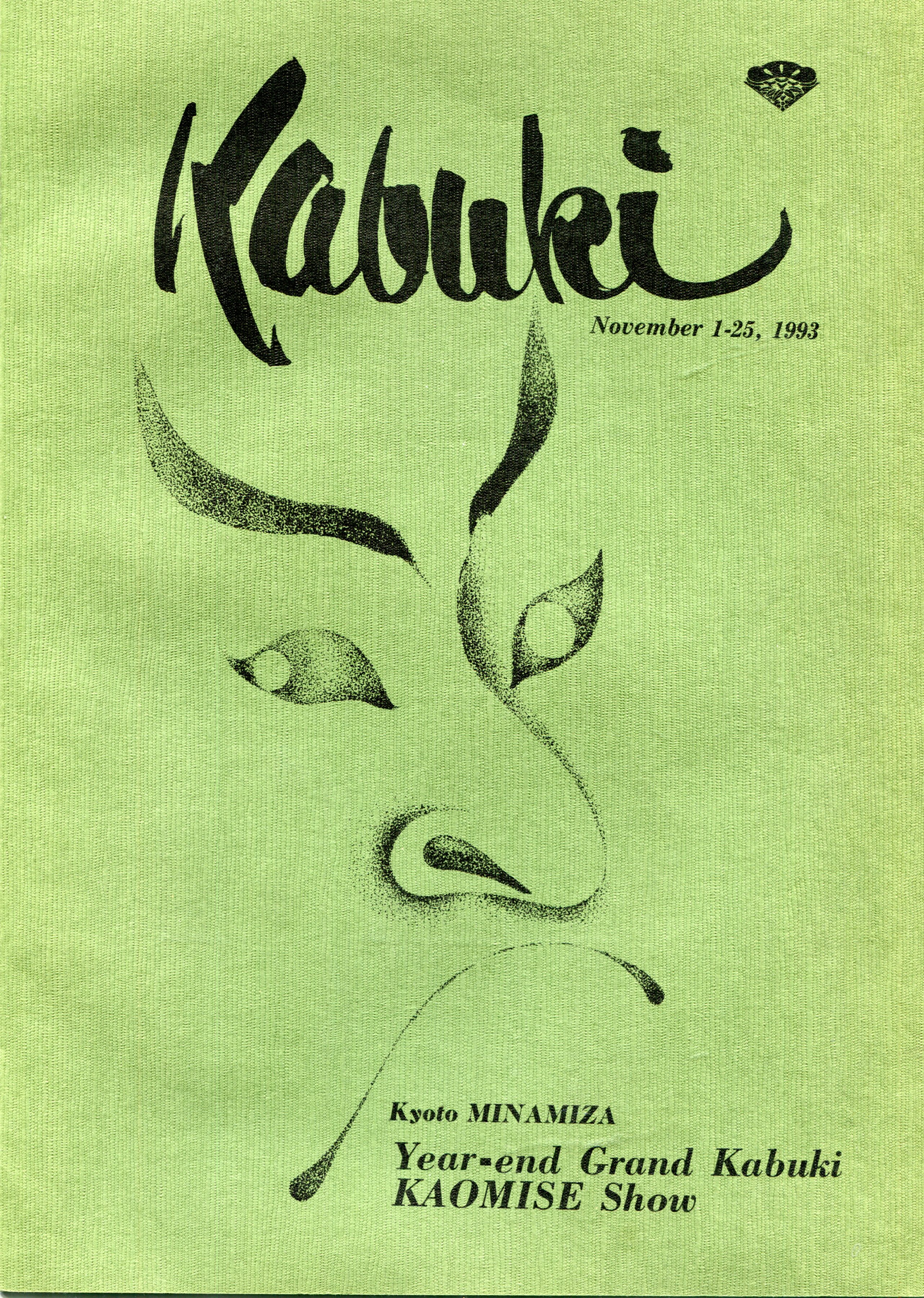

The cover of a 12-page program, from among the debris of previous years. Such items accumulate if you let them, and we do, to remind ourselves of previous years.

Except I can’t say I have anything more than a vague memory of attending the Year-End Grand Kabuki Kaomise show in November 1993. There were actors in wildly colorful costumes and makeup, pursuing their exaggerated movements, as you’d expect. The dialect, Yuriko said, was sometimes hard for her to understand. I only picked up a word here and there sometimes.

“Kabuki theatre has been the most popular indigenous theatre form in Japan since the late 17th century,” explains the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (of all places). “Accompanied by music, the all-male group of actors perform a rich combination of dialogue, song and dance that even encompasses acrobatics, action-packed heroic tales, tragic love stories and burlesque comedies.

“By the 19th century, the best-loved actors and scenes from the most successful plays had quickly become part of an elaborate marketing system that was in part fueled by the proliferation of affordable woodcut prints which drew on the cult status of the stars they depicted.

“One of the high points in the theatre calendar was the wave of premières marking the season’s opening, held annually in the eleventh month of the moon [sic] calendar, during which it was customary for a theatre’s entire ensemble to present a play to the fans. This event is known as ‘kaomise,’ which literally means ‘the showing of faces’ and took its name from the fact that all stars employed for the coming season presented themselves to the public.”

I’d say the Japanese have seen a vast expansion of entertainment forms since the 19th century, just like everyone else, rendering kabuki a niche interest. I’m glad I went, but never felt the urge to go again.