For years, I’ve seen the following two points of interest routinely included on road maps of Illinois. At least, on Rand McNally and Michelin: the Norwegian Settlers State Memorial and the Wild Bill Hickok State Memorial.

When it comes to points of interest on commonly available road maps, there must be just a touch of the arbitrary in their selection. Just a touch, because certainly mapmakers have their editorial standards. Still, I see those (typically) red dots and wonder not only what it is, but also why is that on the map and not something else?

Guess being a state memorial or monument helps land a place on maps. (That link is part of a larger list.)

One goal of our recent trip was to avoid large highways, which we mostly did until we headed for home, when we wanted a more speedy return. When heading out, we kept to smaller roads. One of these was Illinois 71, which passes through the unincorporated community of Norway.

Not far from Norway is the the Norwegian Settlers State Memorial. It’s an example of the plaques-on-rocks school of memorial design, along with a wooden structure, and U.S. and Norwegian flags.

“This Memorial commemorates the 1834 settlement at Norway, Illinois — the first permanent Norwegian settlement in the Midwest,” says the State Historic Preservation Office. “A departure point for many Norwegians who settled other parts of the Midwest, Norway became known as the ‘mother settlement.’ The monument, dedicated in 1934, honors the community and its founder, Cleng Peerson (1783-1865).”

“This Memorial commemorates the 1834 settlement at Norway, Illinois — the first permanent Norwegian settlement in the Midwest,” says the State Historic Preservation Office. “A departure point for many Norwegians who settled other parts of the Midwest, Norway became known as the ‘mother settlement.’ The monument, dedicated in 1934, honors the community and its founder, Cleng Peerson (1783-1865).”

Peerson got around. Though he led immigrants to the New World, he didn’t seem to be interested in settling for more than a few years at a time himself. According to Wiki, he even spent time in Bishop Hill among its Swedish settlers. I guess he had no hard feelings against those oppressors of the Norwegian people. He ended up in Texas in the mid-19th century, as a lot of people did.

Why three stones? One from 1934 memorializes the 100th anniversary of the settlement of Norway, Illinois. Another from 1975 memorializes the 150th anniversary of Norwegians first coming to America en masse. The King of Norway came for that occasion. And yet another (also 1975) notes that part of Illinois 71 is the Cleng Peerson Memorial Highway.

That’s not all. The wooden structure — which I assume is an homage to Norwegian design — has text front and back. Three separate plaques on the front, dated 1980, tell the “Norsk Story,” that is, Norwegians coming to America.

Two more plaques on back (from 1982, bicentennial of Peerson’s birth) offer more detail about the memorial, including lines about Lester Severskie (1918-82) who was “dedicated to the preservation of the Norwegian heritage of Norway, Ill.”, a list of the Norwegian heritage organizations in the U.S. as of 1982 (I had no idea there were so many), and a few lines to thank Olav V, members of the Norwegian government, and so on and so forth.

This has to be the wordiest memorial I’ve ever encountered. It’s the memorial equivalent of a logorrheic movie star upon winning an Oscar. I usually enjoy reading obscure plaques, but these tried my patience, especially in the high heat of July. (The rest of my family was sitting in air-conditioned comfort in the car.)

Even so, I’m glad I stopped. Especially because I noticed that behind the memorial is a small cemetery. The Cleng Peerson Memorial Cemetery, according to one source (who spells cemetery wrong), though I didn’t see any signs or plaques at all about it, just the headstones. According to another source, it’s the Nelson Cemetery.

Whatever the name, it must be an active local cemetery. At least one burial was fairly recent.

Whatever the name, it must be an active local cemetery. At least one burial was fairly recent.

Peerson himself isn’t there. He’s buried near Clifton, Texas.

Peerson himself isn’t there. He’s buried near Clifton, Texas.

In a different context, you might call Peerson an empresario, along the lines of Stephen F. Austin in Texas, except that he was merely a leader of immigrants, not someone who was granted land by an existing government. Except that in the end, he was granted land by Texas, but for services rendered in populating the state with hardy Norwegians, not as an incentive to bring them.

Returning from the Illinois River Valley on Sunday, I made a point of stopping at the Wild Bill Hickok State Memorial in Troy Grove, Illinois. Wild Bill isn’t buried there either. He died in Deadwood, after all, and he rests there in Boot Hill.

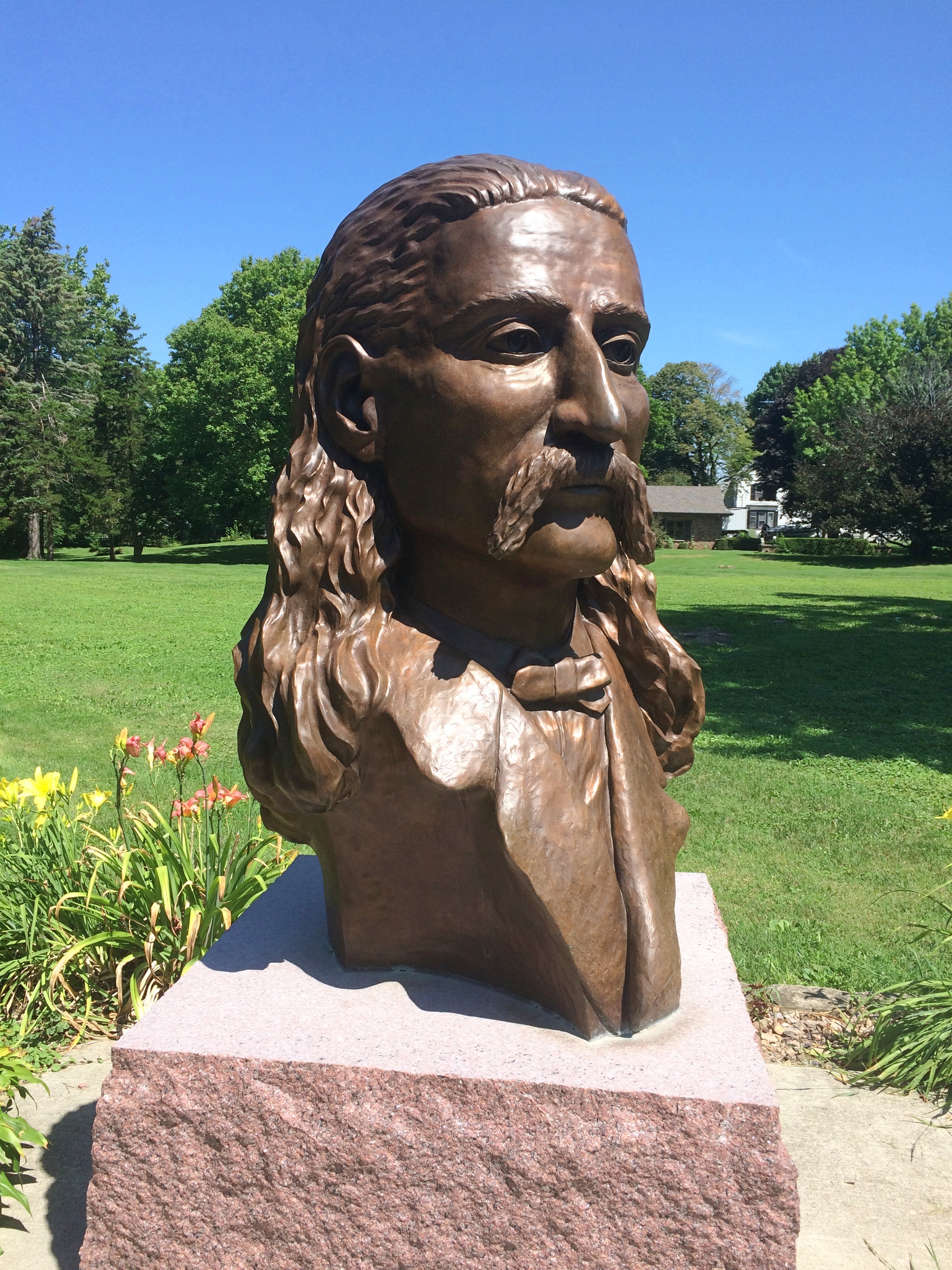

Rather, the memorial marks the birthplace of James Butler Hickok, scout, spy, lawman, soldier, marksman, gambler, showman, folk hero, and dime novel and movie and TV character. It’s at the center of an open patch of land where the Hickok family home once stood, and includes one plaque and one bust.

The state of Illinois erected the plaque in 1929, and it wasn’t shy about lionizing Wild Bill. It needed a proofreader, too.

The state of Illinois erected the plaque in 1929, and it wasn’t shy about lionizing Wild Bill. It needed a proofreader, too.

“He contributed largely in making the West a safe place for woman [sic] and children,” the plaque says in part. “His sterling courage was aways [sic] at the service of right and justice.”

“He contributed largely in making the West a safe place for woman [sic] and children,” the plaque says in part. “His sterling courage was aways [sic] at the service of right and justice.”

The bust is more recent. I had to look it up, because I couldn’t find anything on site — not a word — to say who created it or when.

The state of Illinois says a “log-carved bust” of Hickok was added in 1999, but that’s no wooden bust. It took a little looking, but I found out that “in 2009, an attractive bronze bust of Hickok by artist William Piller was placed in the park. It replaced a carved wooden bust that had been in place 10 years but had severe weather damage,” according to the Danville, Illinois, Commercial-News.

The state of Illinois says a “log-carved bust” of Hickok was added in 1999, but that’s no wooden bust. It took a little looking, but I found out that “in 2009, an attractive bronze bust of Hickok by artist William Piller was placed in the park. It replaced a carved wooden bust that had been in place 10 years but had severe weather damage,” according to the Danville, Illinois, Commercial-News.

Though it was a hot day, I wasn’t quite done with Troy Grove, pop. 230. A building near the memorial caught my eye. (The rest of my family was sitting in air-conditioned comfort in the car.)

Bank, eh? Well, not any more. Still, it’s a handsome little building. A detail toward the top further got my attention.

Bank, eh? Well, not any more. Still, it’s a handsome little building. A detail toward the top further got my attention.

A logo marker apparently left by the Bankers Electrical Protection Co. of Minneapolis: a guard dog close to a money bag. The company seems to have specialized in bank vaults and other security features for banks of yore. You know, the sort of banks at risk from unauthorized withdrawals by the likes of the Cream Can Gang.

Besides a few images, I haven’t found out much else about BEPCo. (as it surely would be called now), mostly since I don’t feel like it. Enough to assume that it went out of business or was acquired by another security company long ago. Yet traces remain, in stone no less.