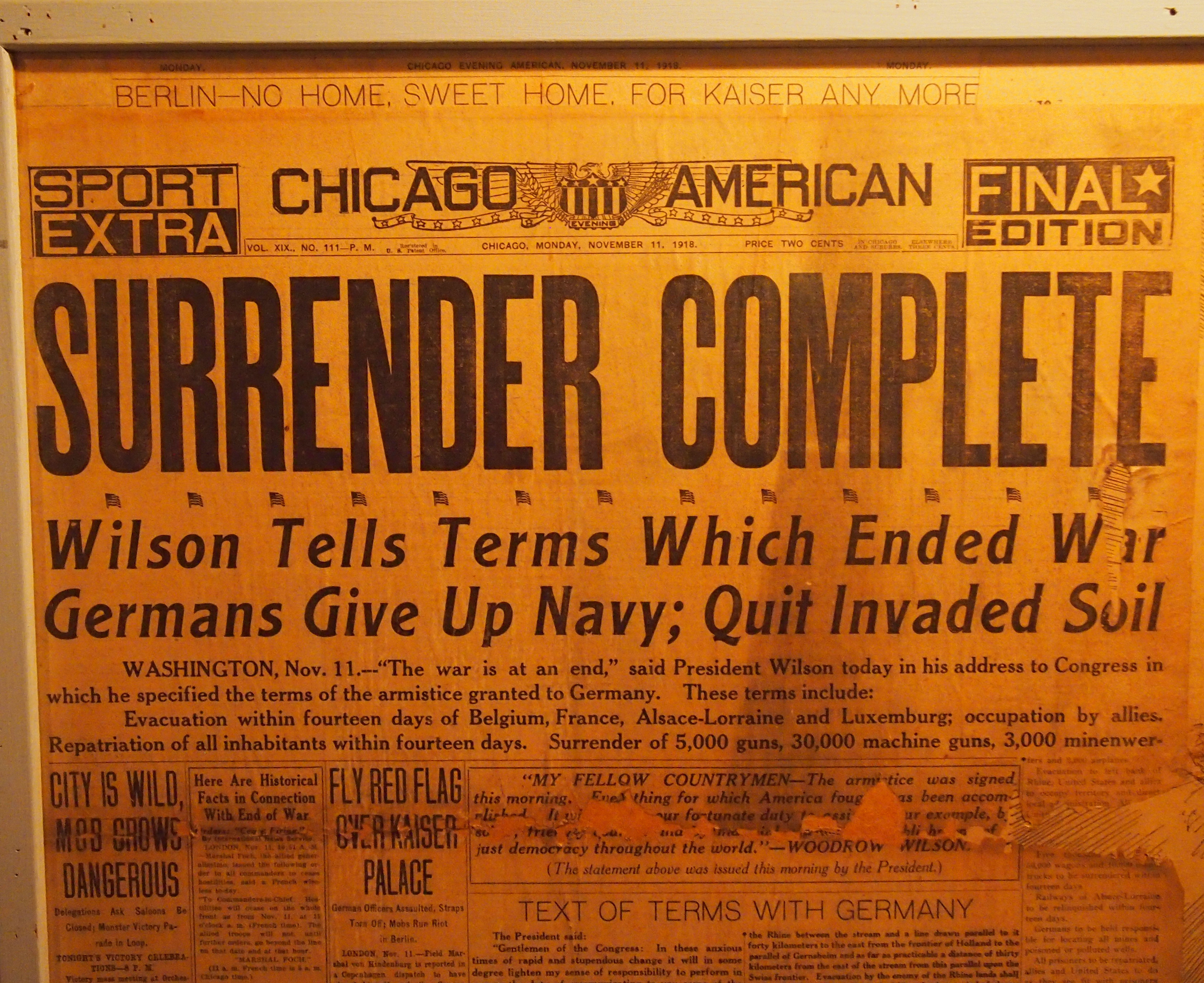

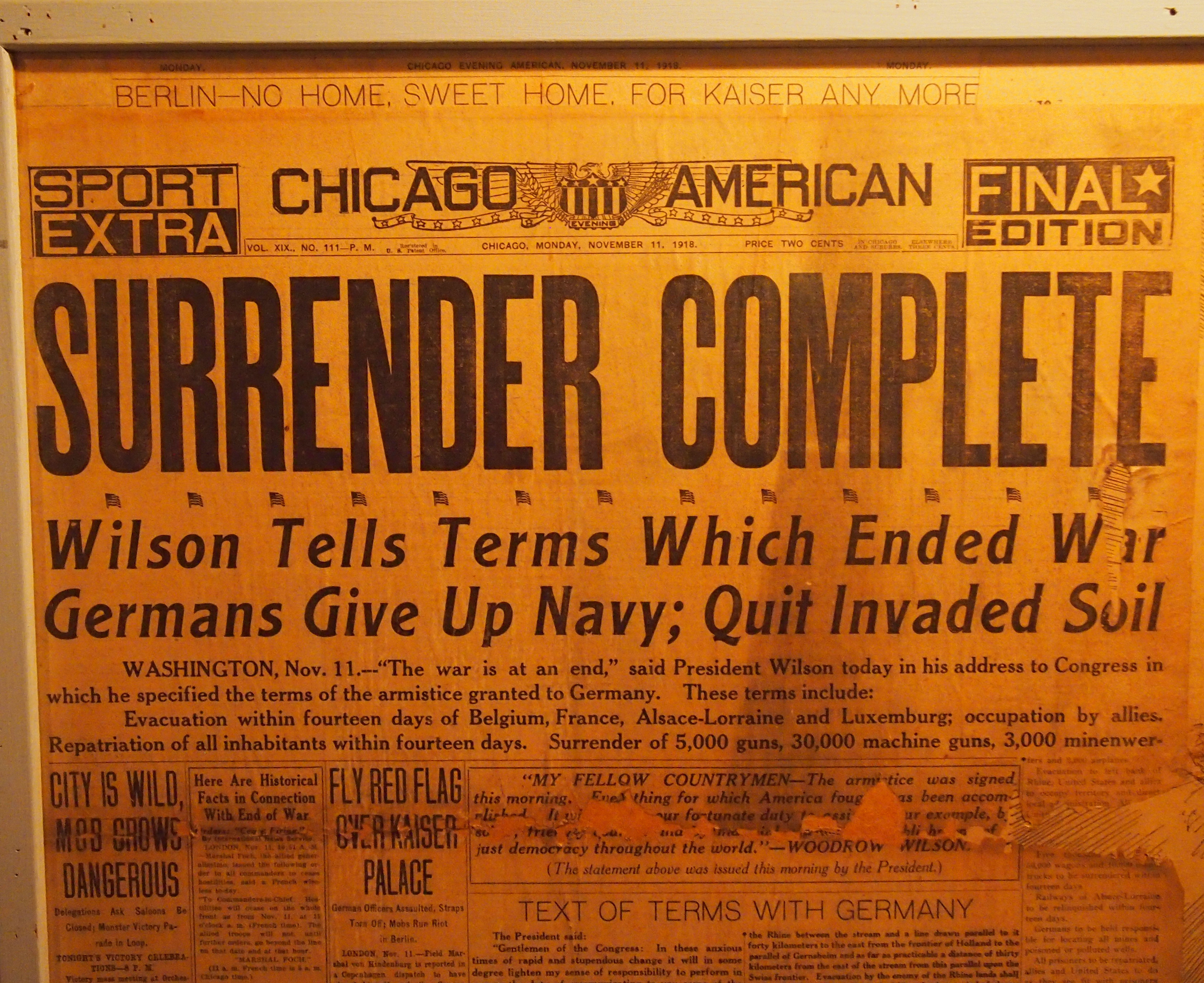

Front page of the Chicago American, November 11, 1918, now on display at the House on the Rock, Wisconsin.

A fine collection of Armistice Day photos — the first Armistice Day, that is — can be found here.

A fine collection of Armistice Day photos — the first Armistice Day, that is — can be found here.

Front page of the Chicago American, November 11, 1918, now on display at the House on the Rock, Wisconsin.

A fine collection of Armistice Day photos — the first Armistice Day, that is — can be found here.

A fine collection of Armistice Day photos — the first Armistice Day, that is — can be found here.

Time for another fall break. Just because. Back to posting around Sunday, November 16, the day that I briefly believed, 17 years ago, was going to be the birthday of my eldest child. But no, that was just Braxton Hicks contractions or something.

Actually, I’m going to set something to post automatically on at 11 a.m. on November 11, because I can’t miss that. I’m not sure why I’m sentimental about Armistice Day, a day that my generation never knew, but I am.

Firstworldwar.com, “a multimedia history of World War I,” has a searchable day-by-day history of the war, and the entry for November 11, 1914, tells me the following.

Western Front

Ypres: Some British trenches penetrated by the Prussian Guard, but recovered.

Southern Front

Serbia: The Serbians in retreat; their headquarters moved from Valyevo to Kraguyevats.

Asiatic and Egyptian Theatres

Mesopotamia: British outposts attacked at Saniya.

Naval and Overseas Operations

H.M.S. Niger sunk by German submarine.

Political, etc.

Great Britain: Parliament opened; the King’s Speech

It’s probably just as well that the participants couldn’t know that they still had four more years to go.

I’m the only one that’s going to call yesterday’s snow the Armistice Day Snow of 2013, but I’m peculiar that way. The name echoes the Armistice Day Blizzard of 1940, but of course yesterday’s event wasn’t nearly as severe, or unexpected. The Minnesota Historical Society remembers 1940. So does Ludington, Mich.

Or call it the Veterans Day Snow of 2013. It was strange to watch snowflakes blow by and the ground whiten up this early.

Thought so. She’s an Illinois hound, after all, and her coat has been noticeably thickening in recent weeks.

Thought so. She’s an Illinois hound, after all, and her coat has been noticeably thickening in recent weeks.

“The Armistice” by Eugene Savage, on display at the Elks National Veterans Memorial, Chicago.

Posted nearby is the following:

The principal figure near the center is the Madonna, the Mother of Christ, the Prince of Peace. She portrays the bereaved mother with raised hands in a gesture of stopping contending forces from opposite sides. She looks down sorrowfully upon the figure of Hope, now chained to a gun carriage, symbolizing ruthless force. Those who have come to grief and defeat in the trenches are crawling out. An old clock, stopped at the Hour of Eleven, indicates the significant hour of the signing of the Armistice – the 11th Hour of the 11th Day of November, 1918. The idols and gold cloth flung about represent the ruthless destruction of churches and things made by Man. The hands pointing accusing fingers and the expression of horror on the faces of the soldiers on the top right effectively recall the unspeakable Horror of War. Balancing this are the American Soldiers, on the left, with Smiles of Joy, who are beginning the Celebration of the End of the War. They have just heard the news of the Armistice, and are ringing a bell salvaged from the ruins, upon which they carry a French peasant girl. The Dove, Olive Branch and Rainbow fill out the scene, indicating Promise of a New Peace.

“The elks live up in the hills and in the spring they come down for their annual convention. It is very interesting to watch them come down to the water hole. And you should see them run when they find that it’s only a water hole. What they’re looking for is elk-ohole.”

– Capt. Jeffery T. Spaulding

I was winding down by around 4 p.m. on October 19, but I wanted to see one more place. It wasn’t far north of Mother Cabrini’s shrine, and also at one of the edges of Lincoln Park: the Elks National Veterans Memorial. I could see its Roman-style dome from quite a distance in the park.

After the Great War, the Elks wanted to build a memorial to their members who had died in the conflict, which numbered more than 1,000, as well as space for the org’s national headquarters. The main rotunda of the Elks National Veterans Memorial was the most ornate space I saw during Openhousechicago, though Mother Cabrini’s shrine was a close second.

After the Great War, the Elks wanted to build a memorial to their members who had died in the conflict, which numbered more than 1,000, as well as space for the org’s national headquarters. The main rotunda of the Elks National Veterans Memorial was the most ornate space I saw during Openhousechicago, though Mother Cabrini’s shrine was a close second.

This was no accident. The Elks War Relief Commission, which was tasked with supervising the building’s construction, wrote in its recommendation to the Grand Lodge in 1921 that: “The suggested building be made definitely monumental and memorial in character; that the architectural design be so stately and beautiful, the material of its construction so enduring, its site and setting so appropriate… that the attention of all beholders will be arrested, and the heart of every Elk who contemplates it will be thrilled with pride, and that it will for generations to come prove an inspiration to that loyalty and patriotism which the Order so earnestly teaches and has so worthily exemplified.”

The order picked New York architect Egerton Swarthout to design the memorial. He had a predilection for Beaux-Arts, which shows in the Elks memorial. More than shows, it overflows. I wouldn’t want everything to be done in that style, but it has its place – such as in massive, ornate memorials completed in the 1920s.

My camera, and my skills, aren’t remotely up to capturing the marbles or the soaring murals or even the gilded allegorical statues of the rotunda, which depicted Elk-approved virtues (Brotherly Love, Charity, Fidelity, and Justice). Better to see them with the eye, or failing that, at the memorial’s web site.

By contrast, I gave picture-taking a go at the Grand Reception Room at the Elks National Veterans Memorial. It too is ornate to beat the band.

I was especially taken with the allegorical painting called “The Armistice,” which of course references November 11, 1918. Eugene Savage did that work and others in the room, and I thought that style looked familiar. Like a WPA work, but before that agency existed. Sure enough, Savage was an important player in the WPA Federal Arts program, so I guess that was no accident either.