Things to bring to Colonial Williamsburg: money, walking shoes, water (especially in summer) and — I can’t stress this enough — some historical imagination. Not everyone has much. I understand that. Still, if you can’t bring much historical imagination to your visit, best to go somewhere else.

A look at a few of the recent “terrible” reviews of Colonial Williamsburg on TripAdvisor illustrates the point (all sic).

Mrpetsaver: This place is like that fort or museum with old buildings common in some communities, but on a larger scale.

My kids got bored very quickly and so did I. Most of the staff are great and professional dressed up in costumes, but aren’t acting. Instead, they discuss how the original inhabitants did their different jobs etc.

Dewpayne: It has some very interesting sites but there so far away you get bored it’s more about the shops and selling water I wouldn’t recommend it.

zebra051819: This historical site was a huge disappointment and I would not recommend spending your time here. There must be more informative sites where one could gain an appreciation of Civil War history.

Mrpetsaver is right, though. Colonial Williamsburg is a larger version of an open-air museum. It is an open-air museum. One on a grand scale, the likes of which we’d only experienced — sort of — at Greenfield Village.

Colonial Williamsburg shouldn’t be confused with Williamsburg, Virginia, which is a town of around 14,500 on the lower reaches of the James River. As a 21st-century American town, it has the usual amenities, such as honky-tonks (maybe), Dairy Queens and 7-11s, where you can buy cherry pies, candy bars and chocolate-chip cookies.

Colonial Williamsburg, on the other hand, occupies 173 acres and includes 88 original buildings and more than 50 major reconstructions. All of Colonial Williamsburg is within modern Williamsburg, but not all of modern Williamsburg involves Colonial Williamsburg. A fair bit of it doesn’t, according to maps.

A hundred years ago, Williamsburg was a small college town with a history, namely as the second capital of Virginia when it was a prosperous tobacco colony. No doubt the story of how Colonial Williamsburg came to be in the early 20th century is fairly complicated, with a number of major players, but I’m going to oversimplify by saying that Money wanted it to happen, as persuaded by Preservationism.

Money in the form of Rockefeller scion John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had the deep pockets necessary to start the purchase and restoration of the historic sites, and Preservationism in the form of W.A.R. Goodwin (1869–1939), rector of Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg, who felt alarmed that the 20th century was eating away at the area’s historic structures.

Colonial Williamsburg is a odd hybrid of past and present, but also of museum and neighborhood. The foundation that runs the museum doesn’t play it up — and some of the disappointed TripAdvisor reviews note it ruefully — but it turns out that you don’t need a ticket to wander along the streets of Colonial Williamsburg.

Cars aren’t allowed on the streets during museum hours, but visitors are perfectly free to park a few blocks away and walk around. That’s because the town of Williamsburg still owns the streets and sidewalks, making them public thoroughfares.

Also — another thing the foundation doesn’t dwell on — people live in Colonial Williamsburg. “There are dozens of people — families, couples, college students — who live in some of the historic homes of Colonial Williamsburg,” says Local Scoop. “Many of the homes are original colonial-era buildings; others were rebuilt based on historical accounts to look like the homes they once were.

“It’s not a perk available to everyone. To live in the Historic Area, one has to work at Colonial Williamsburg or be an employee at the College of William & Mary. In all, there are 75 houses rented through the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation…”

I found this out when I was there, and pretty soon I started noticing that a fair number of the houses had small signs denoting them as private residences. I also noticed a few people doing neighborhood sorts of things, like jogging or walking their dogs, as opposed to tourist sorts of things.

So why buy a ticket? That’s so you can see the interiors of the many buildings flying the Grand Union flag. They mark the open-air museum’s buildings.

Also, your ticket gets you into some Colonial Williamsburg events, many of which involve reenactors. So we got tickets. At $45 each, and no student discount (grumble), that’s more than Henry Ford/Greenfield, in the same league as some theater tickets and some theme parks, and less than other theme parks (whose mascot is a Mouse).

Also, your ticket gets you into some Colonial Williamsburg events, many of which involve reenactors. So we got tickets. At $45 each, and no student discount (grumble), that’s more than Henry Ford/Greenfield, in the same league as some theater tickets and some theme parks, and less than other theme parks (whose mascot is a Mouse).

At that price, I was determined to wear out my feet. So we did, spending October 14 from late morning to late afternoon at Colonial Williamsburg. At the end, I felt like I’d gotten my money’s worth. I’m a sucker for open-air museums, for one thing, but more than that, it is a special place with a lot to see and think about, if you add a dash of historical imagination.

You walk from the visitor center along a wooded path until you come to the historic buildings. The first one of any heft is the Governor’s Palace.

Maybe no grand thing back in England, but for colonial Virginia, a worthy residence for the gov. What you see now is a reconstruction from plans and, according to the guide on the interior tour that we joined, archaeological investigation of the materials left when the building collapsed in a fire in 1781, not long after Gov. Jefferson had decamped to Richmond.

Maybe no grand thing back in England, but for colonial Virginia, a worthy residence for the gov. What you see now is a reconstruction from plans and, according to the guide on the interior tour that we joined, archaeological investigation of the materials left when the building collapsed in a fire in 1781, not long after Gov. Jefferson had decamped to Richmond.

When it burned, the structure was being used as a hospital for men wounded at the Battle of Yorktown. All of them but one escaped the fire, the guide said. I told Ann we should listen for that unfortunate fellow’s ghost. She told me to shush.

From there we wandered down the Palace Green to Duke of Gloucester St., pretty much the main street of the historic area. The view from the other end of the Palace Green.

Nearby is the Bruton Parish Church. It isn’t one of the Colonial Williamsburg buildings, but people go in as if it were. We did. A couple of parishioners were on hand to tell visitors about the church.

Nearby is the Bruton Parish Church. It isn’t one of the Colonial Williamsburg buildings, but people go in as if it were. We did. A couple of parishioners were on hand to tell visitors about the church.

The building dates from the 1710s, but according to this history, it didn’t look much like the original by the mid-1800s, after various alterations and modernizations. Like Colonial Williamsburg, the church was restored to its 18th-century appearance only in the early 20th century.

The building dates from the 1710s, but according to this history, it didn’t look much like the original by the mid-1800s, after various alterations and modernizations. Like Colonial Williamsburg, the church was restored to its 18th-century appearance only in the early 20th century.

The church’s graveyard was fenced in, but you could get a pretty good look at it anyway.

Some of the stones were close to the church itself.

Some of the stones were close to the church itself.

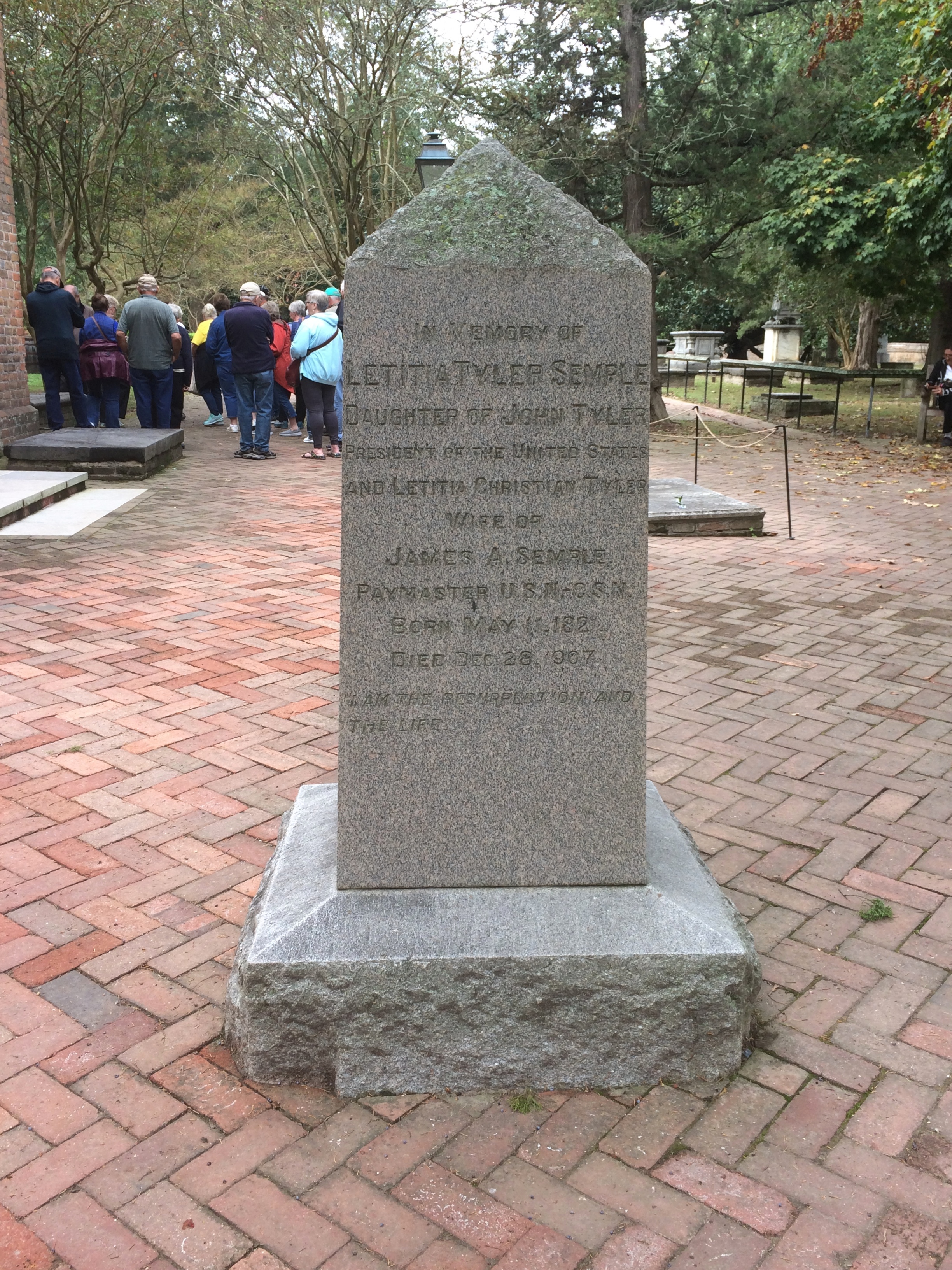

The stone of Letitia Tyler Semple, one of President Tyler’s many children. A handful of stones were inside, flush with the floor of the church, as you see in old English churches. W.A.R. Goodwin has one of those.

The stone of Letitia Tyler Semple, one of President Tyler’s many children. A handful of stones were inside, flush with the floor of the church, as you see in old English churches. W.A.R. Goodwin has one of those.

We spent the rest of the day looking at and entering various structures on or near Duke of Glouchester St., such as the Geddy Foundry, the Courthouse, the Market Square, the Magazine, the Printing Office, the Silversmith, Bakery, Apothecary, and Raleigh Tavern, where we saw two reenactors: one playing Marquis de Lafayette and other James Armistead Lafayette, who spied for the Patriots at the Marquis’ request, and, after some inexcusable delays by the state of Virginia, finally won his freedom for his service.

Duke of Glouchester St.

The Magazine and its arms.

The Magazine and its arms.

The Courthouse and nearby stocks. No rotten tomatoes on hand for tossing.

The Courthouse and nearby stocks. No rotten tomatoes on hand for tossing.

Botetourt St.

The reconstructed Capitol was the second-to-last place we visited, taking a late-afternoon tour. Nicely done, I thought, though the authenticity of the redesign has been questioned.

The reconstructed Capitol was the second-to-last place we visited, taking a late-afternoon tour. Nicely done, I thought, though the authenticity of the redesign has been questioned.

The last place was Charlton’s Coffeehouse, where a foundation employee (“costumed interpreter”) in 18th-century garb showed us around and served visitors either coffee, tea or hot chocolate. Most of us tried the chocolate, as Ann and I did. Colonial hot chocolate included a variety of flavors not usually associated with modern hot chocolate. If I remember right, almonds, cinnamon and nutmeg in our case, but no rum. Our time is decidedly more abstemious than Colonial days when it comes to alcohol. Tasty anyway.

The last place was Charlton’s Coffeehouse, where a foundation employee (“costumed interpreter”) in 18th-century garb showed us around and served visitors either coffee, tea or hot chocolate. Most of us tried the chocolate, as Ann and I did. Colonial hot chocolate included a variety of flavors not usually associated with modern hot chocolate. If I remember right, almonds, cinnamon and nutmeg in our case, but no rum. Our time is decidedly more abstemious than Colonial days when it comes to alcohol. Tasty anyway.

Some people expect the costumed interpreters to be actors (see above). To varying degrees they were in character, but mostly their job was to explain what went on in a particular building, and in the places like the foundry and silversmith and printing office, demonstrate some of the 18th-century work techniques. I had no complaints.

The fellow in the foundry turned out pewterware before our eyes and the young woman who showed us around the coffeeshop was informative and entertaining, telling us for instance the story of the tax collector (under the Stamp Act, I believe) who was greeted at the coffeehouse by a committee (mob) of citizens who suggested he find other work for himself. Wisely, he did.

There are restaurants at Colonial Williamsburg in some of the “taverns,” but I didn’t want to spend time at a sit-down restaurant when there were other things to see. So we subsisted on snacks during the visit, which are available in Colonial-themed small stores here and there on the grounds.

The 21st-century snacks were good.