There’s probably no way to measure this, but I believe that the George Rogers Clark Memorial, which looks very much like it belongs on the National Mall or somewhere equally prominent, is the most obscure large memorial in the country. Who’s ever heard of it, especially outside Indiana? But at more than 80 feet high and 90 feet across at the base, with walls two feet thick, it cries out to be acknowledged as Founding Father-class memorial. The structure is the centerpiece of the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, which is near the Wabash River in Vincennes, Indiana, just across from Illinois. In early 1779, when Indiana and Illinois were unrealized political entities contingent on a Patriot victory in the Revolution, Fort Sackville stood on the site — more or less. It was around the area somewhere, and occupied by a British garrison.

The structure is the centerpiece of the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, which is near the Wabash River in Vincennes, Indiana, just across from Illinois. In early 1779, when Indiana and Illinois were unrealized political entities contingent on a Patriot victory in the Revolution, Fort Sackville stood on the site — more or less. It was around the area somewhere, and occupied by a British garrison.

Above the memorial’s 16 Doric columns, the inscription says: The Conquest of the West – George Rogers Clark and The Frontiersmen of the American Revolution.

In a tour de force, days-long maneuver in the dead of a Midwestern winter, George Rogers Clark led the forces that assaulted Fort Sackville and took it from the British. But that was just the climax of his efforts.

In a tour de force, days-long maneuver in the dead of a Midwestern winter, George Rogers Clark led the forces that assaulted Fort Sackville and took it from the British. But that was just the climax of his efforts.

“Clark began his campaign of attempting to weaken the British position by influencing the French settlers in the area to support the American cause,” the NPS says. “Through these efforts, Clark was able to capture the Illinois Country posts of Kaskaskia, Prairie du Rocher, and Cahokia. Soon after, this French influence was extended over 150 miles to the settlers in Vincennes, and they also declared themselves allies to the Americans.

“… George Rogers Clark in the late summer of 1778 [was] in Cahokia, at a council he called with local Indian tribes in an effort to negotiate peace. By convincing [British Lt. Gov. Henry] Hamilton’s Indian allies to switch sides, Clark could further diminish the resources available to the British.

“Although Clark’s forces at this council were far outnumbered by the Indians in attendance, he impressed the warriors with his bold manner. Many of the leaders of these tribes were convinced to accept the white belt of peace rather than the red belt of war. While this council certainly strengthened Clark’s efforts, there were still many tribes who chose to continue their alliances with the British.”

In older histories, at least, Clark is thus credited with allowing the United States to acquire the Northwest Territory under the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Of course, more recent historians disagree about how important Clark’s campaign was in influencing that outcome, as historians do.

Probably the Crown considered that part of North America lost anyway, since newly independent Americans would surely pour into the territory. On the other hand, who knows? Had there been a British garrison in Indiana, and more British-aligned Indians, they might have tried to hang on to the area, as they did Canada.

Also, just in passing, Clark established a settlement in Kentucky that would become Louisville. Finally, he’s William Clark’s elder brother; he of Lewis & Clark fame, whom everyone has heard of. So why is George Rogers Clark so obscure? (Well, not completely to Hoosiers.)

Such is the ebb and flow of historic reputation. Still, Clark got himself a spiffy monument eventually, at the insistence of the people of Vincennes and probably a fair number of Indiana politicians in Washington, around the time of the 150th anniversary of the battle.

New York architect Frederic Charles Hirons designed the memorial, and it was considered important enough for President Roosevelt himself to come dedicate it in 1936 (though the Coolidge administration got the process started).

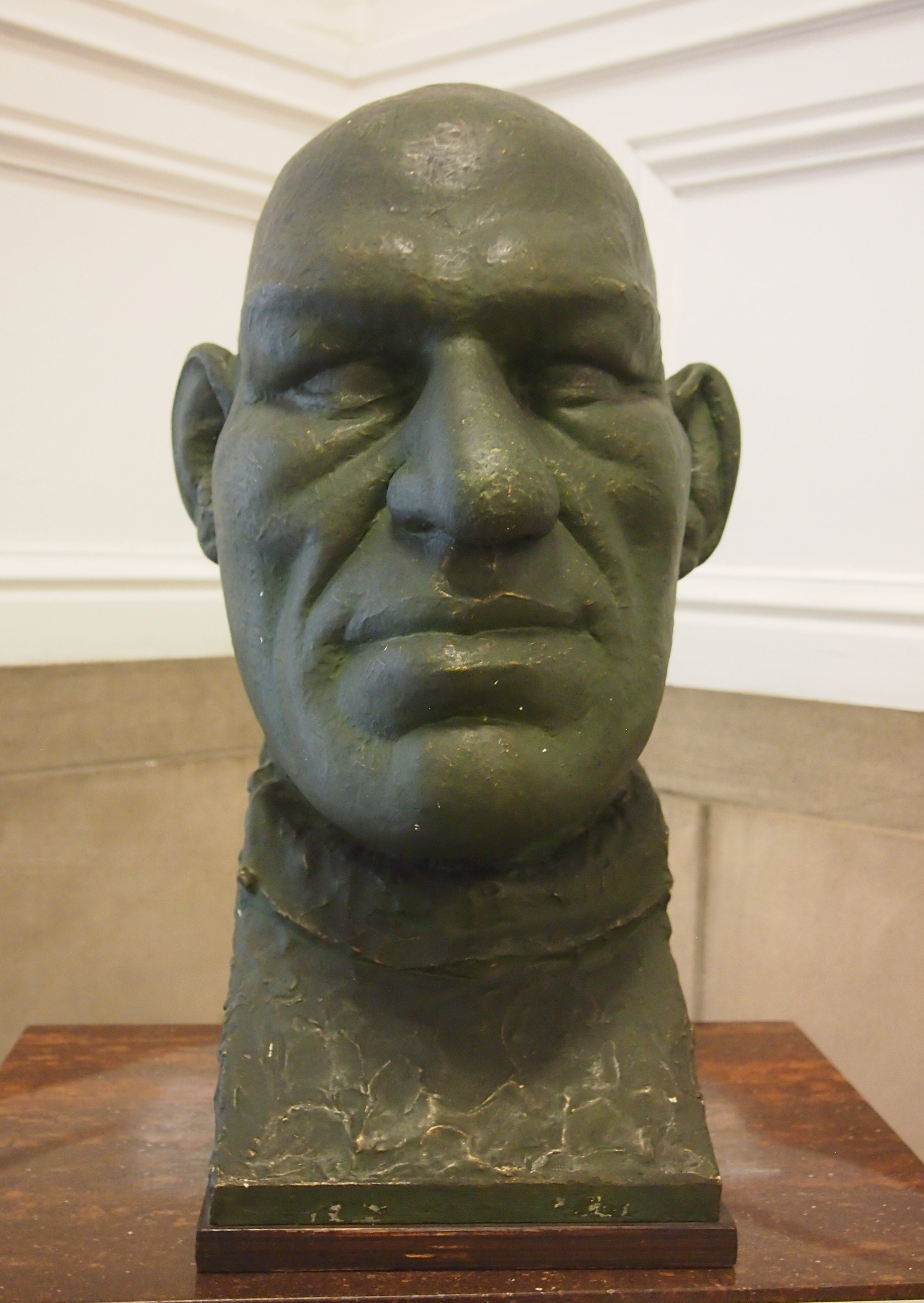

Inside — air conditioned in our time, a good thing — is a bronze of Clark. On the floor is Clark’s statement to the Virginia Council in 1775, requesting aid for Kentucky: If a country is not worth protecting, it is not worth claiming.

Hermon Atkins MacNeil did the sculpture. I’d heard of him already — he also designed the aesthetic Standing Liberty Quarter, which I’d argue we should go back to, once Washington’s been on the quarter 100 years (coming up in 2032).

The murals depicting the campaign are by Ezra Winter. Some details:

After I wrote about Geo. Rogers Clark and his NHP, I mulled over how many National Historical Parks there are, and how many I’ve been to. Fifty-one all together — not the same as National Historical Sites, of which there are 78. I remember visiting 13 such NHPs, two of which were only this year, though I might have forgotten a few. As for sites, only 11. I need to get out more.

After I wrote about Geo. Rogers Clark and his NHP, I mulled over how many National Historical Parks there are, and how many I’ve been to. Fifty-one all together — not the same as National Historical Sites, of which there are 78. I remember visiting 13 such NHPs, two of which were only this year, though I might have forgotten a few. As for sites, only 11. I need to get out more.

No event was going on when we were there, but it was a pleasant place to hang out. I did that while everyone else went shopping at the adjacent retail. If I remember right, they found some spring clothes.

No event was going on when we were there, but it was a pleasant place to hang out. I did that while everyone else went shopping at the adjacent retail. If I remember right, they found some spring clothes.