I’ve read that the first floor of the Newberry Library on the Near North Side of Chicago is newly renovated, and it did have a newly polished look when Ann and I were there on Saturday. But it’s been a while since I’ve been inside the library, so I don’t really remember what it used to look like.

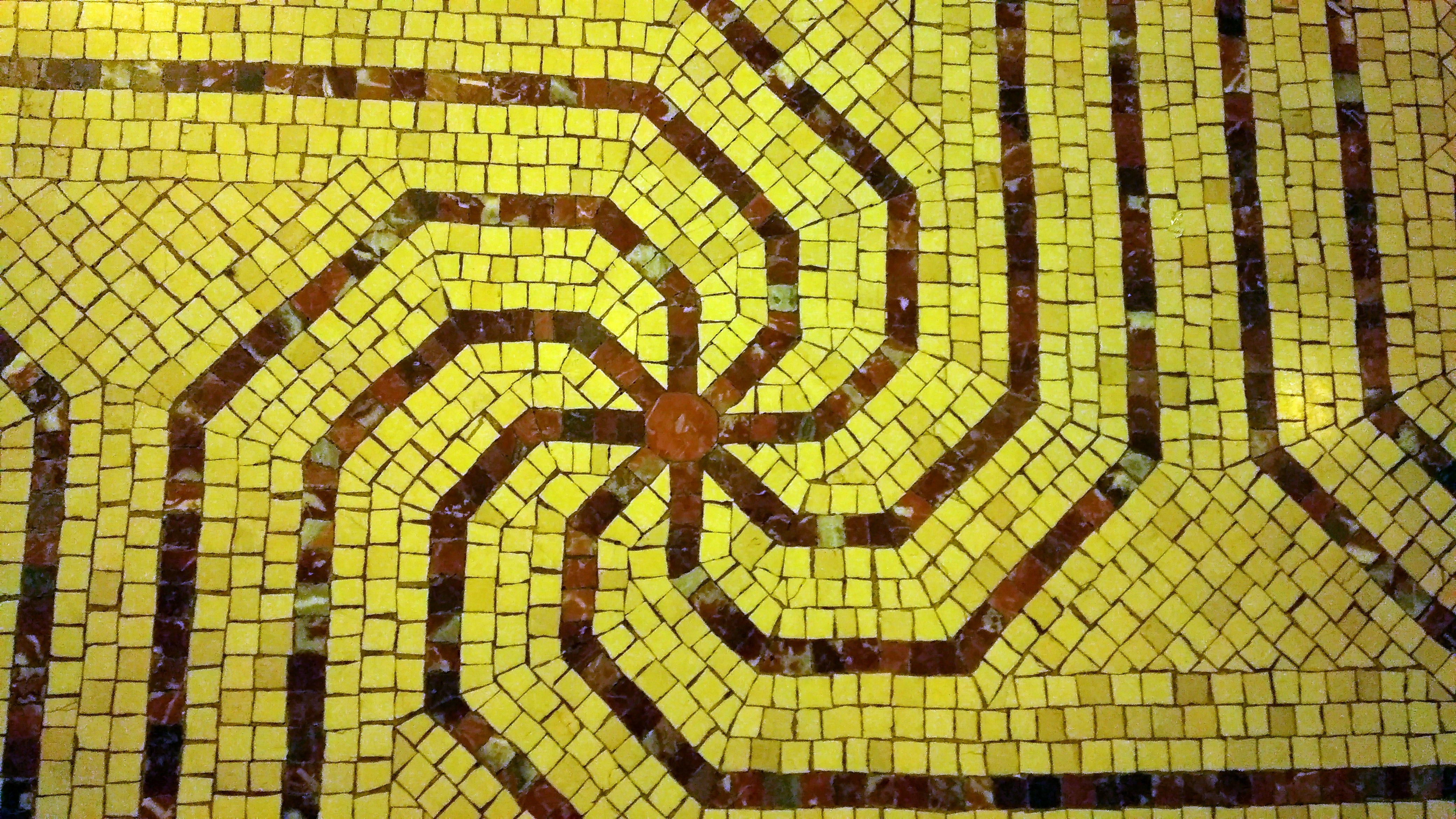

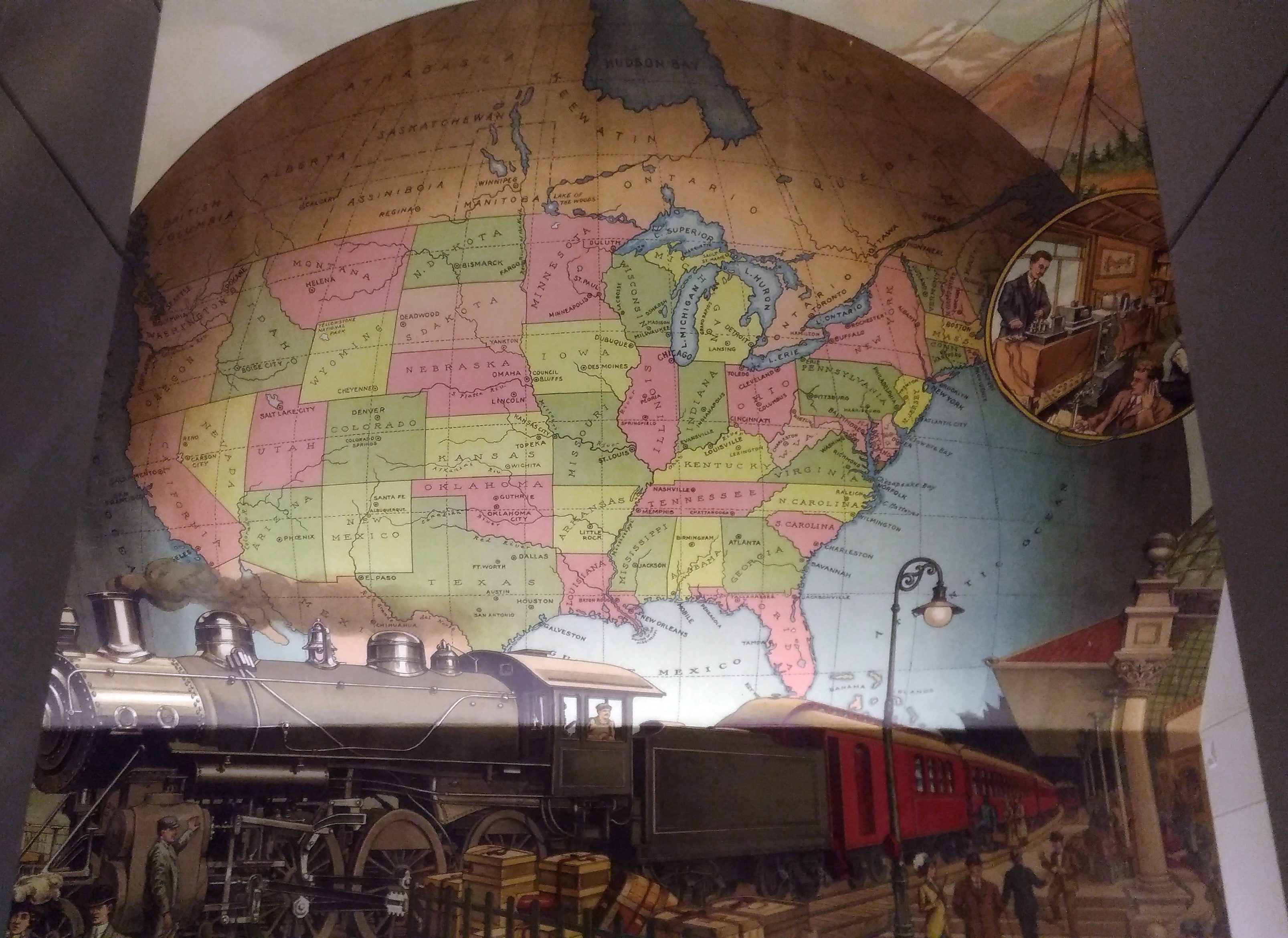

I’m sure that I’d never seen this intriguing mural before, which is above the landing between the first and second floors near a back entrance to the building.

A map mural. Even better, an historic map mural, along with a train at a station under the map and what looks like a telephone and telegraph office in a balloon off to the side.

A map mural. Even better, an historic map mural, along with a train at a station under the map and what looks like a telephone and telegraph office in a balloon off to the side.

The mural looks new, so either it is, or maybe an older image was expertly refurbished. I didn’t see any signs or plaques nearby to tell me which, or who the artist is, and the library web site doesn’t seem to say, so for now I’ll let the matter rest. It’s always good to find a map mural.

My guess is that the map depicts the nation ca. 1900 — united by rail, telegraph and the still fairly new telephone, with a new century of progress to look forward to. Or possibly 1887, when the Newberry was founded, or 1893, when the current building opened.

Though not cartographically precise (West Virginia looks especially mashed), the map’s close enough to evoke the United States of the period. One detail I noticed was that South Dakota’s towns were Deadwood and Yankton, even though the territorial capital moved to Bismarck in 1883 (presumably Al Swearengen would then refer to those “c—suckers from Bismarck” rather than Yankton).

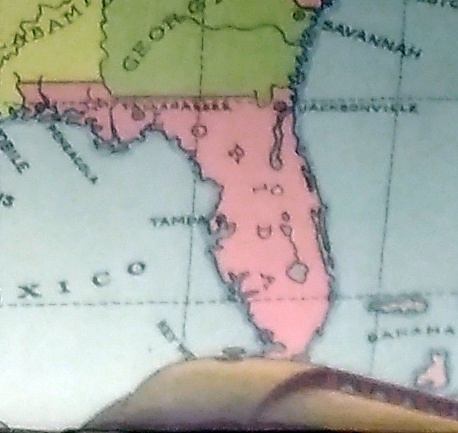

Also, note the pre-land boom, pre-drain the Everglades, pre-Disney, pre-Florida Man Florida.

A little fuzzy, but it’s clear that there’s no Miami and no Orlando.

A little fuzzy, but it’s clear that there’s no Miami and no Orlando.

Also, the states depicted were not quite all states at the beginning of the 20th century. Arizona, New Mexico and what became Oklahoma were still territories.

That would be my only quibble: before it became a state, Oklahoma was actually two territories, the Oklahoma Territory and the Indian Territory. The Indians of the Indian Territory wanted to be admitted as the state of Sequoyah, but Congress wasn’t having it, and so the two territories were joined to form the modern state in 1907.

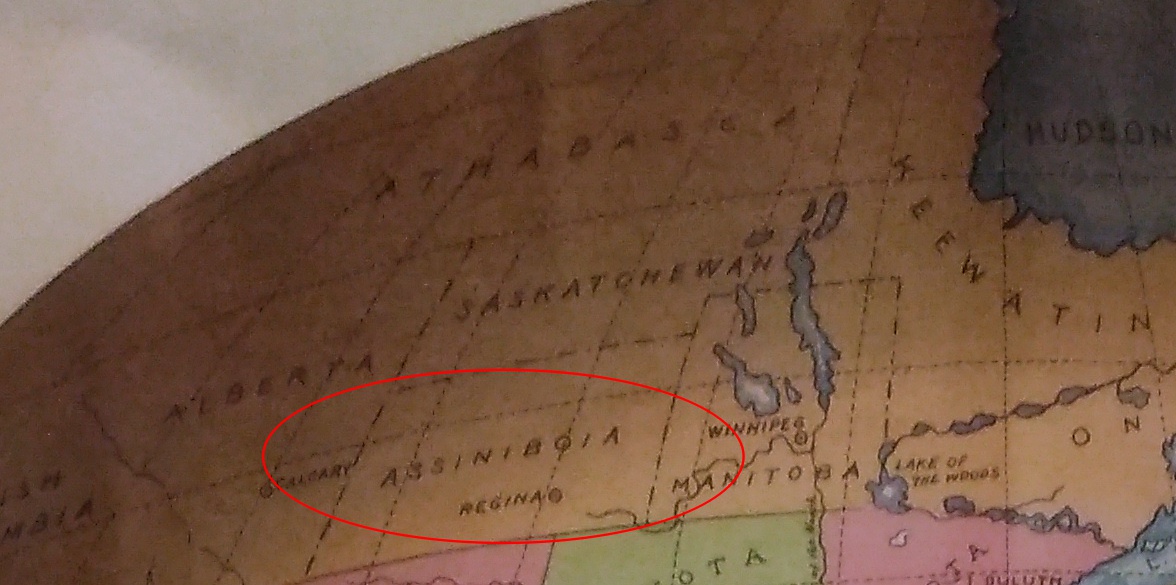

How do I know that the map doesn’t depict borders sometime after 1907? Because of the depiction of Canada.

The wonderfully named Assiniboia was a district of the NW Territories, as were Saskatchewan and Athabasca, all before 1905 (Keewatin was a separate territory before 1905, then became a district of the NWT). A major reorg of prairie Canada was done in ’05, making it look mostly like it does now.

The wonderfully named Assiniboia was a district of the NW Territories, as were Saskatchewan and Athabasca, all before 1905 (Keewatin was a separate territory before 1905, then became a district of the NWT). A major reorg of prairie Canada was done in ’05, making it look mostly like it does now.

So the map depicts pre-1905 Canada, but post-1907 Oklahoma. Ah, well. It’s small quibble about such a fine example of a mural.