Near (or on) Eldorado St. — one of Decatur, Illinois’ main streets — are three small museums. Two are former mansions, one is attached to a factory. I figured we had time for two on Saturday afternoon, but in the end we visited all three.

This is the former mansion of three-time Illinois Governor, U.S. Senator and Civil War General Richard J. Oglesby (1824-99).

I’ve encountered Oglesby, in bronze anyway, in Chicago. He grew up in Decatur and had a successful run as an Illinois lawyer, Union Army officer, and politician. He panned for gold in California, traveled in Europe in the 1850s, married at least one wealthy woman (not sure about his first wife) and knew Lincoln well — was in fact at the Petersen House in Washington City when the Great Emancipator died.

Designed originally in the 1870s by William LeBaron Jenney, father of the skyscraper, in the 21st century the mansion is resplendent, the work of decades of restoration.

The museum’s web site says: “The Library is the most significant room in the house regarding authenticity. It remains as it was built. All the wood is of native black walnut, with the exception of the parquet floor. The original shutters have been reproduced, and glass doors were added to the shelves which were on the architect’s drawings. The books in the cases are Oglesby family books.

“The dining room is the other area that is known to be correct. During the restoration, the complete decoration of the room was found, even the color of the ceiling and all the faux finishes. This room has been reproduced as it was during the Oglesbys’ time in the house.

“The dining room wallpaper was reproduced by a company that was making authentic Victorian wallpapers. All the walls with the exception of the hall and the library are covered with Bradbury and Bradury Wallpaper copied from papers of the time period.

“Furnishings in the home have been chosen for the time period 1860-1885. Most came from old Decatur families. Many of the pieces and the artifacts have come from Oglesby descendants.”

My own favorite artifact is tucked away behind glass: a 19th-century prosthetic leg, that is, a primitive wooden item purported to belong to Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón, Napoleon of the West, and captured at the Battle of Cerro Gordo in 1847 after said Napoleon badly mismanaged things.

The authenticity of the leg hasn’t been confirmed, however. Unlike the other one in Illinois. Per Wiki: “Santa Anna, caught off guard by the Fourth Regiment of the Illinois Volunteer Infantry, was compelled to ride off without his artificial leg, which was captured by U.S. forces and is still on display at the Illinois State Military Museum in Springfield, Illinois.”

Not far from the Oglesby mansion is the Hieronymus Mueller Museum, a different sort of place.

Mueller, as in the Mueller Co. These days headquartered in Tennessee, but for a long time a Decatur company. Even now the company has a factory in Decatur, which is next to the museum. Mueller Co. made, and makes, metal parts and structures and machines. Half of the fire hydrants sold in the United States are Mueller made, for instance.

Mueller, as in the Mueller Co. These days headquartered in Tennessee, but for a long time a Decatur company. Even now the company has a factory in Decatur, which is next to the museum. Mueller Co. made, and makes, metal parts and structures and machines. Half of the fire hydrants sold in the United States are Mueller made, for instance.

But that’s just a part of the output. Many examples of the company’s products are on display at the museum, along with various exhibits about the German immigrant Hieronymus (1832-1900) and his many children and grandchildren.

But that’s just a part of the output. Many examples of the company’s products are on display at the museum, along with various exhibits about the German immigrant Hieronymus (1832-1900) and his many children and grandchildren.

The company dabbled in horseless carriages, but didn’t go whole hog into that.

The company dabbled in horseless carriages, but didn’t go whole hog into that.

It did its part in WWII.

It did its part in WWII.

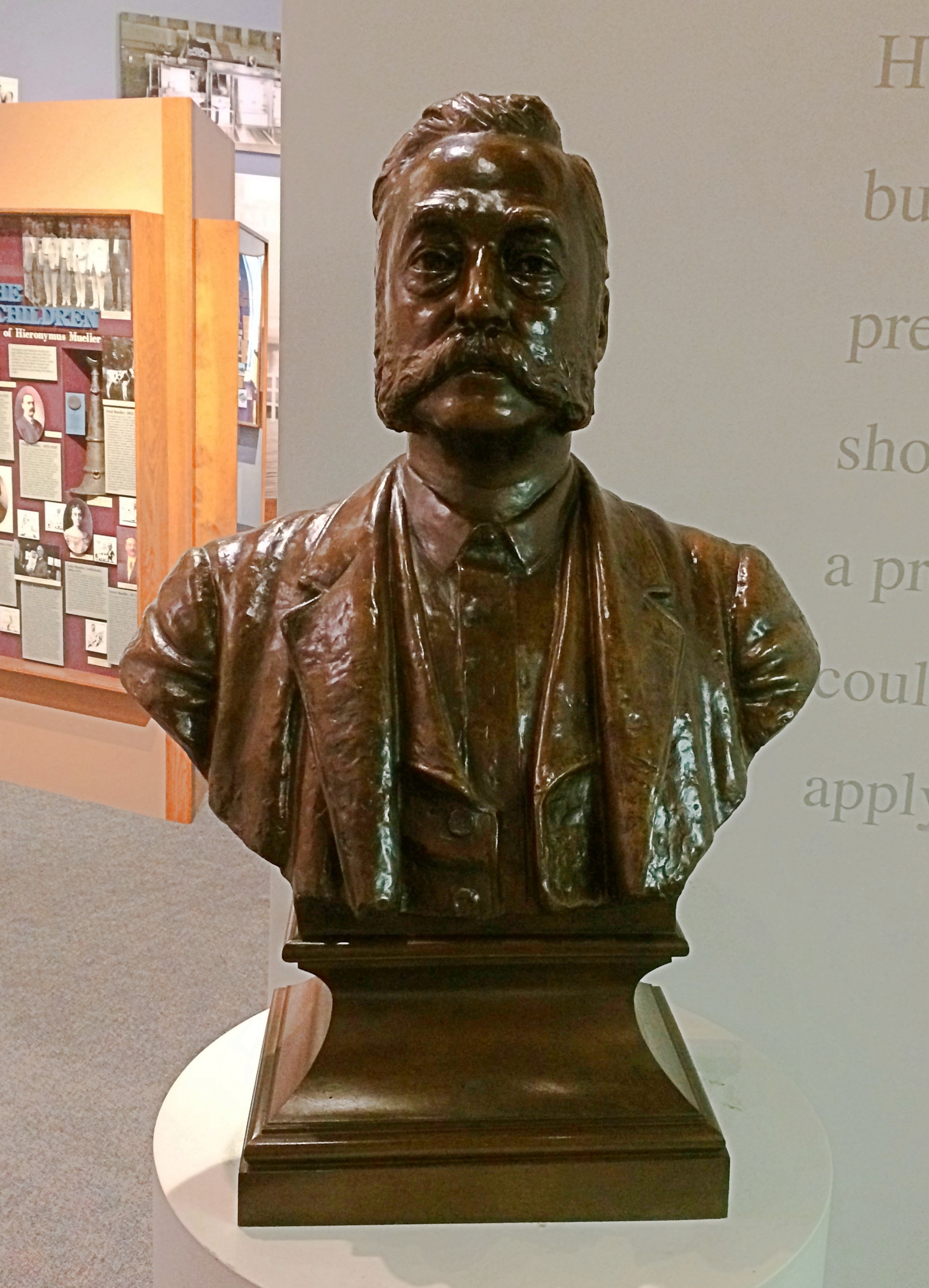

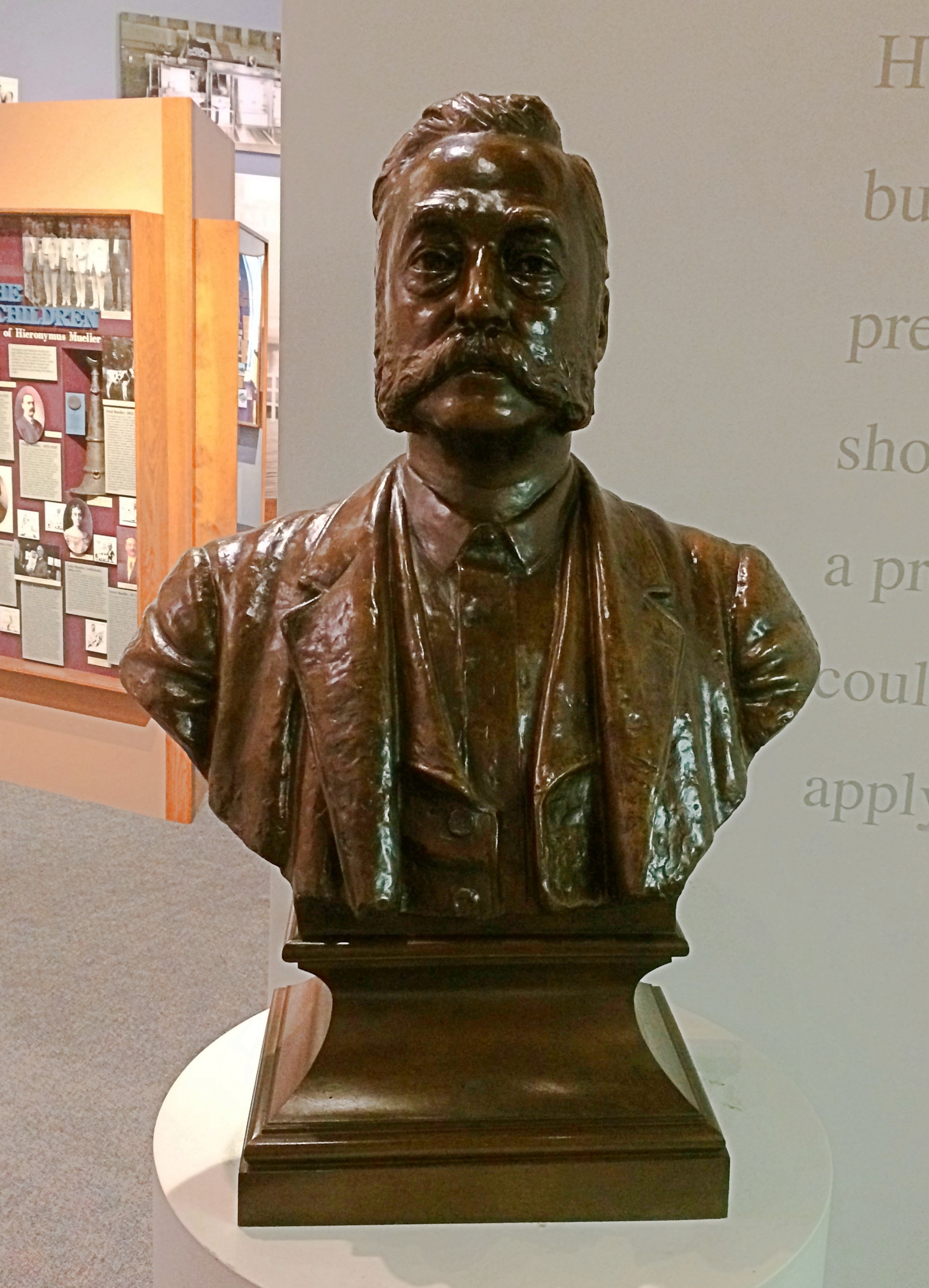

Here’s Hieronymus in bronze. He was a whiz during the golden age of American invention.

Here’s Hieronymus in bronze. He was a whiz during the golden age of American invention.

The museum says: “He started his business with a small gunsmithing shop but soon added locksmithing and sewing machine repairs. He had a knack for understanding mechanical devices. This led to his appointment as Decatur’s first ‘city plumber’ in 1871 to oversee the installation of a water distribution system.

The museum says: “He started his business with a small gunsmithing shop but soon added locksmithing and sewing machine repairs. He had a knack for understanding mechanical devices. This led to his appointment as Decatur’s first ‘city plumber’ in 1871 to oversee the installation of a water distribution system.

“The following year he patented his first major invention, the Mueller Water Tapper who [sic] is, with minor modifications, still the standard for the industry.

“He and his sons went on to obtain 501 patents including water pressure regulators, faucet designs, the first sanitary drinking fountain, a roller skate design, and a bicycle kick-stand. In 1892 Hieronymus imported a Benz automobile from Germany and, together with his sons, began refining it with such features as a reverse gear, water-cooled radiator, newly designed spark plugs, and a make-and-break distributor – all leading to patents.”

Our third and final small Decatur museum for the day: the Staley Museum, one-time house of Decatur businessman A.E. Staley.

Staley was neither politician nor inventor, but had considerable talents as a salesman and ultimately boss man of A.E. Staley Mfg. Co., which started out as a starch specialist and expanded into many other products, mostly made from corn and soybeans. As a child, I ate Staley syrup.

Staley was neither politician nor inventor, but had considerable talents as a salesman and ultimately boss man of A.E. Staley Mfg. Co., which started out as a starch specialist and expanded into many other products, mostly made from corn and soybeans. As a child, I ate Staley syrup.

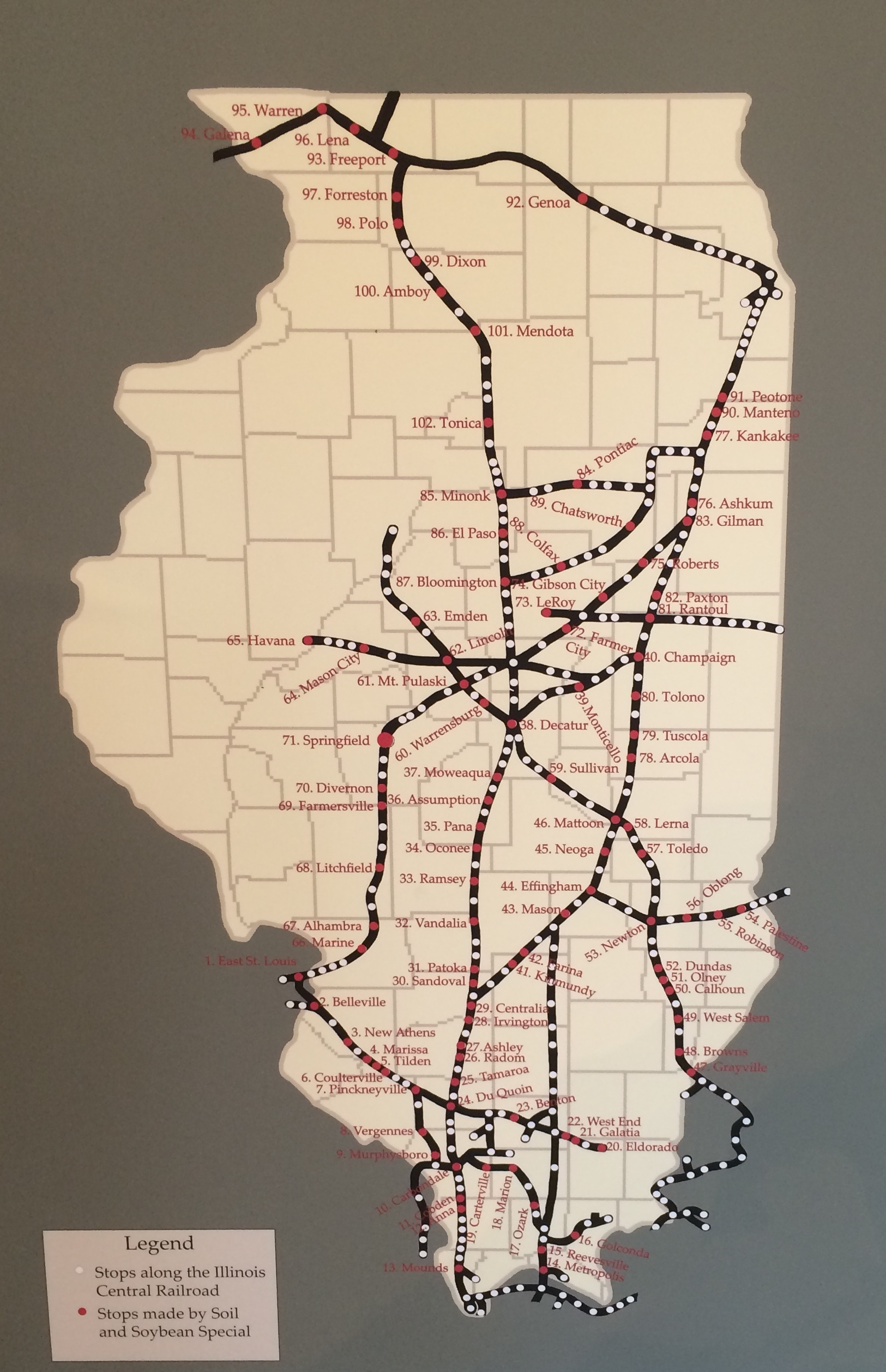

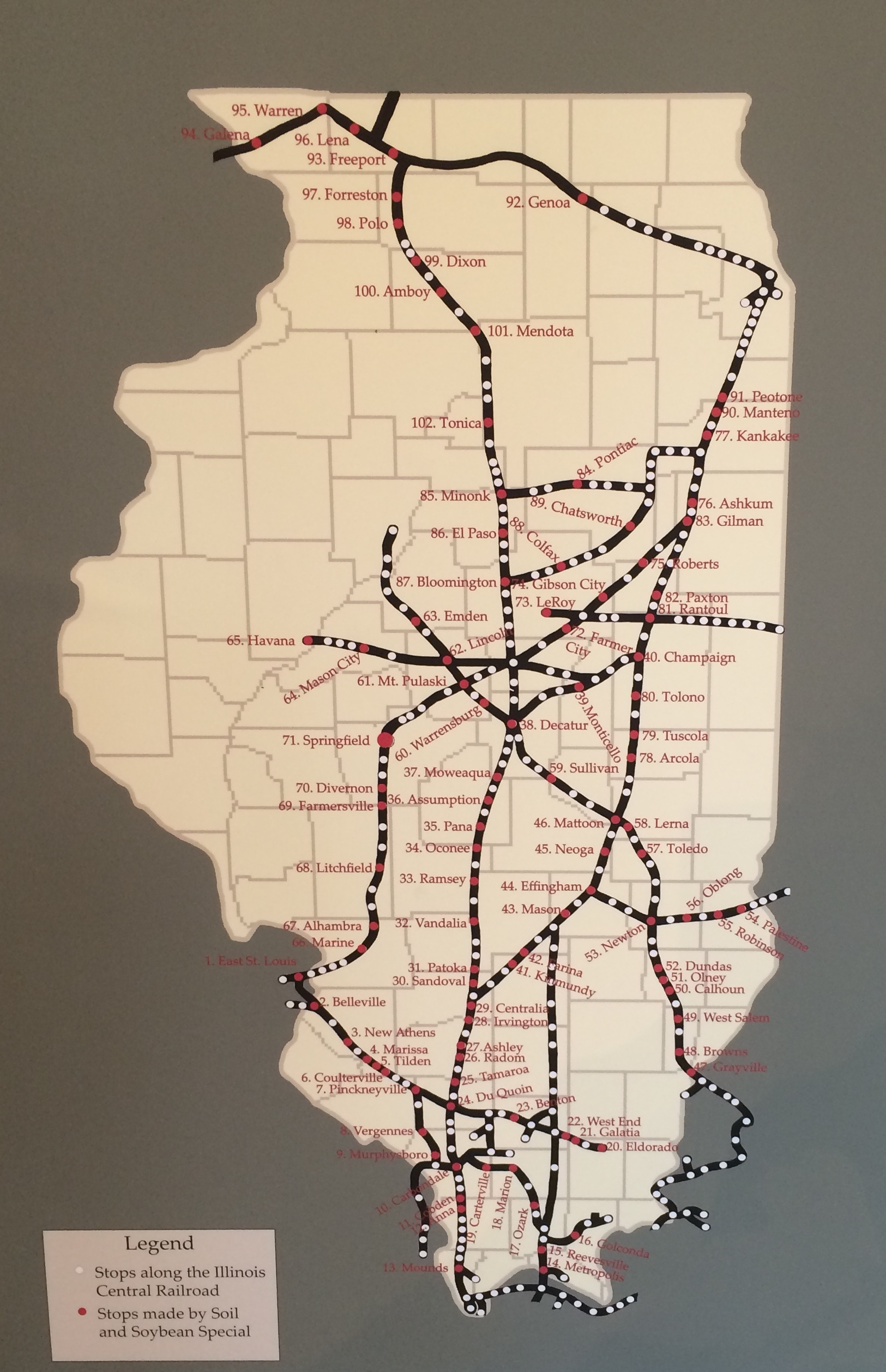

Among other causes, Staley (1867-1940) was a soybean booster. In the spring of 1927, he organized a train to publicize and facilitate soybean cultivation in Illinois, the Soil and Soybean Special.

Among other causes, Staley (1867-1940) was a soybean booster. In the spring of 1927, he organized a train to publicize and facilitate soybean cultivation in Illinois, the Soil and Soybean Special.

As the promotional material with the map says, “This is a farmers’ institute on wheels. If the farmer can’t go to college, this college will come to him.”

As the promotional material with the map says, “This is a farmers’ institute on wheels. If the farmer can’t go to college, this college will come to him.”

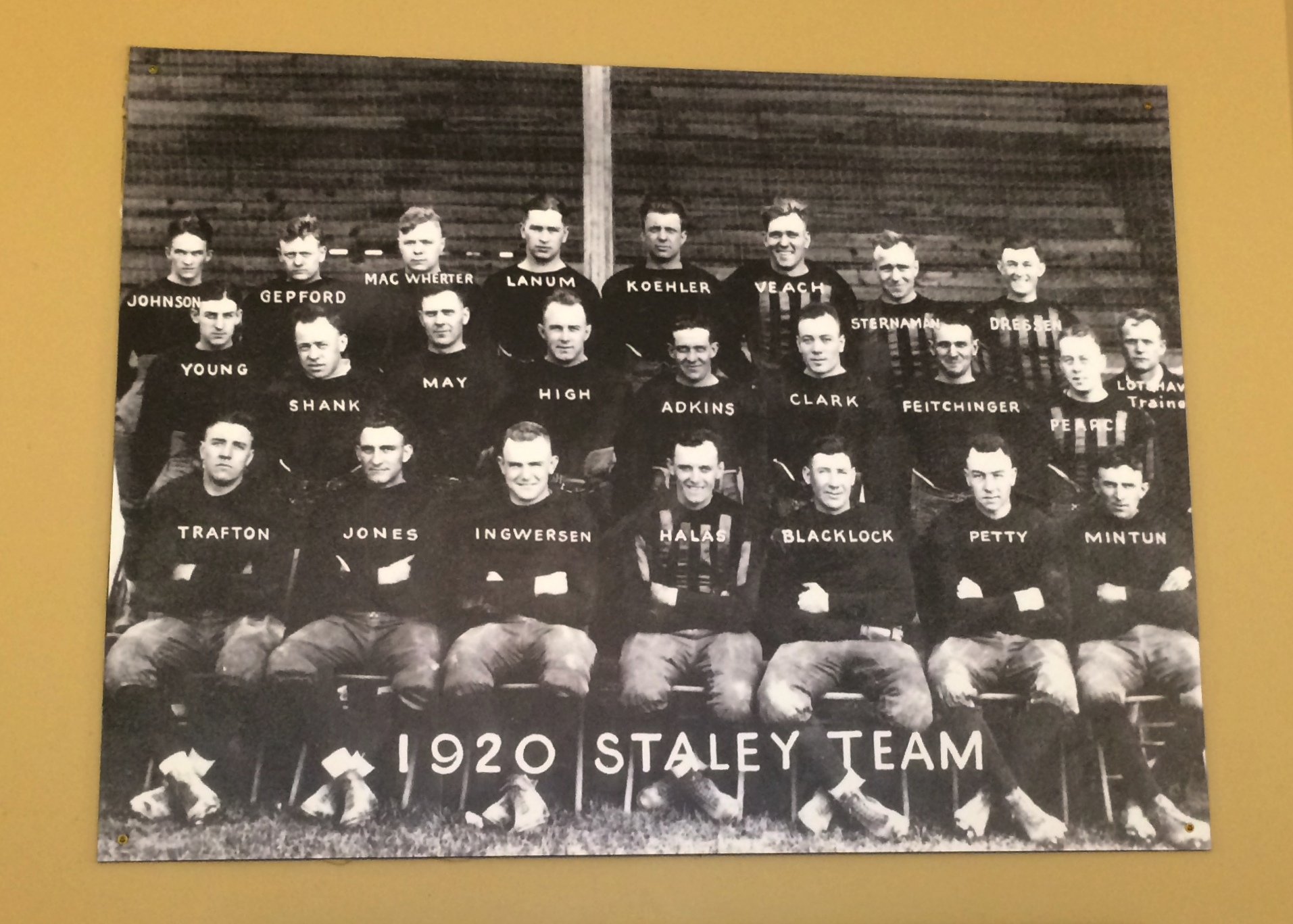

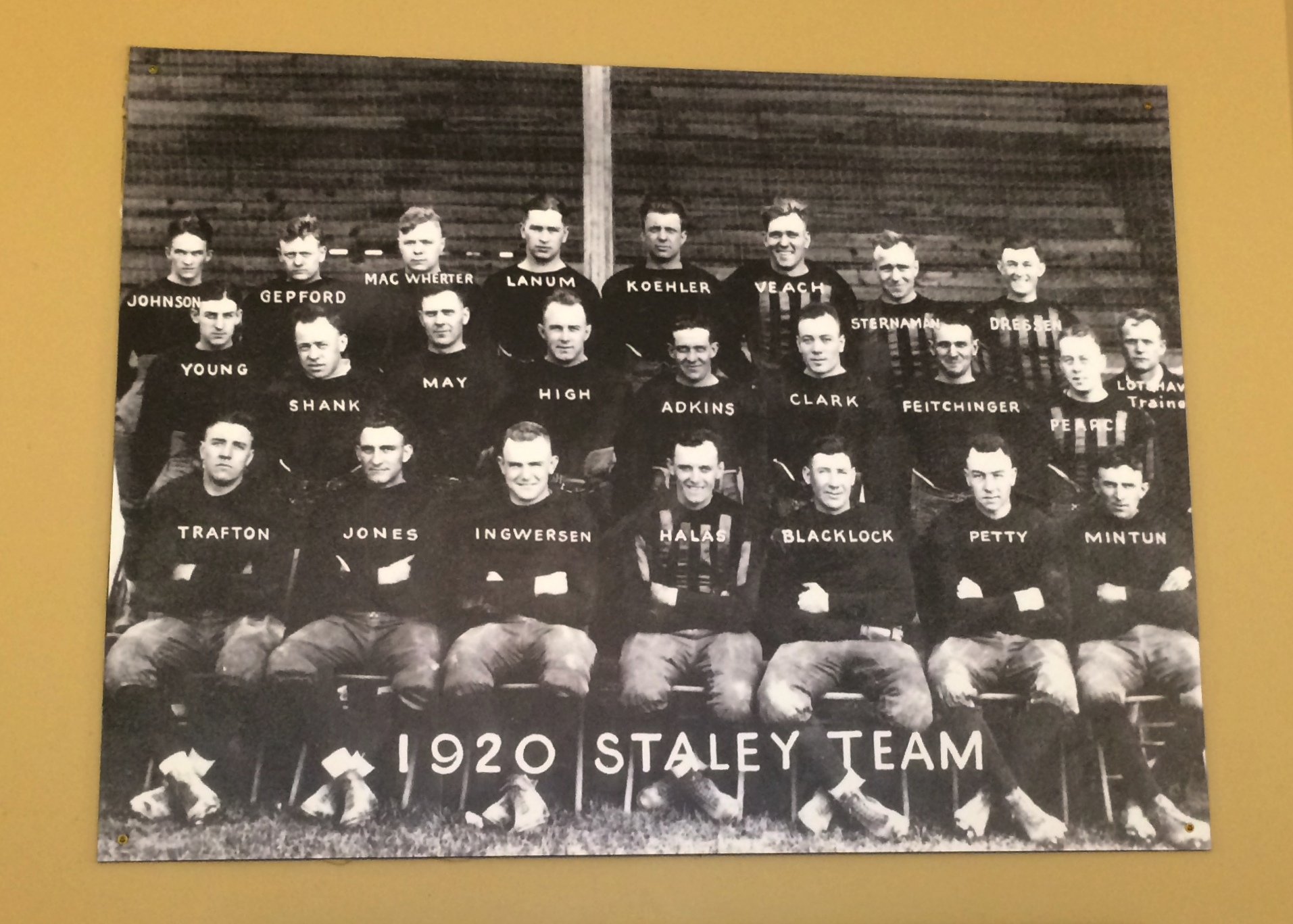

Staley is also known for founding the football team that evolved into the Chicago Bears: the Decatur Staleys, a leather-helmet company team. Here they are in 1920.

The origin of the team isn’t forgotten. Even now, the team mascot is Staley Da Bear.

The origin of the team isn’t forgotten. Even now, the team mascot is Staley Da Bear.

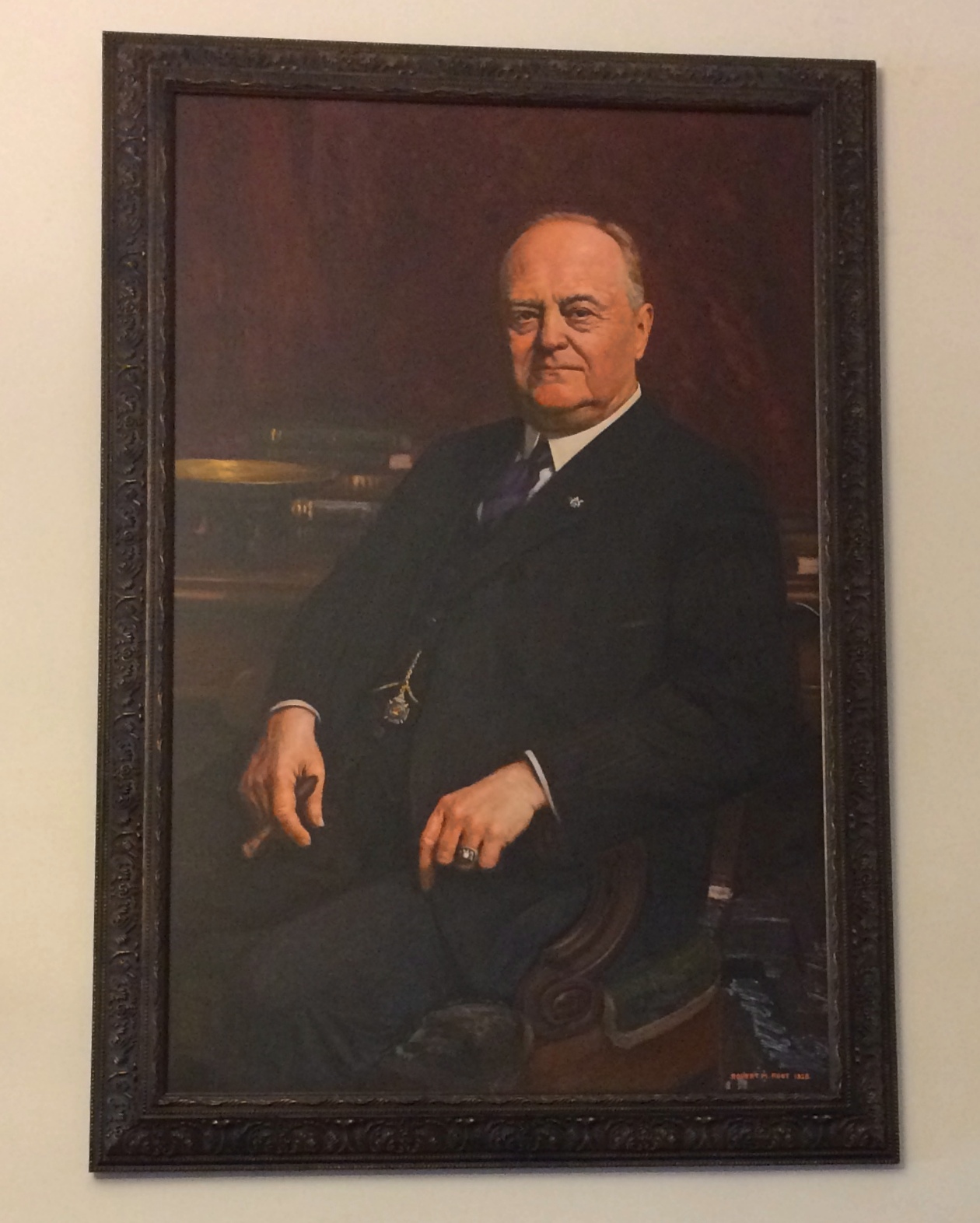

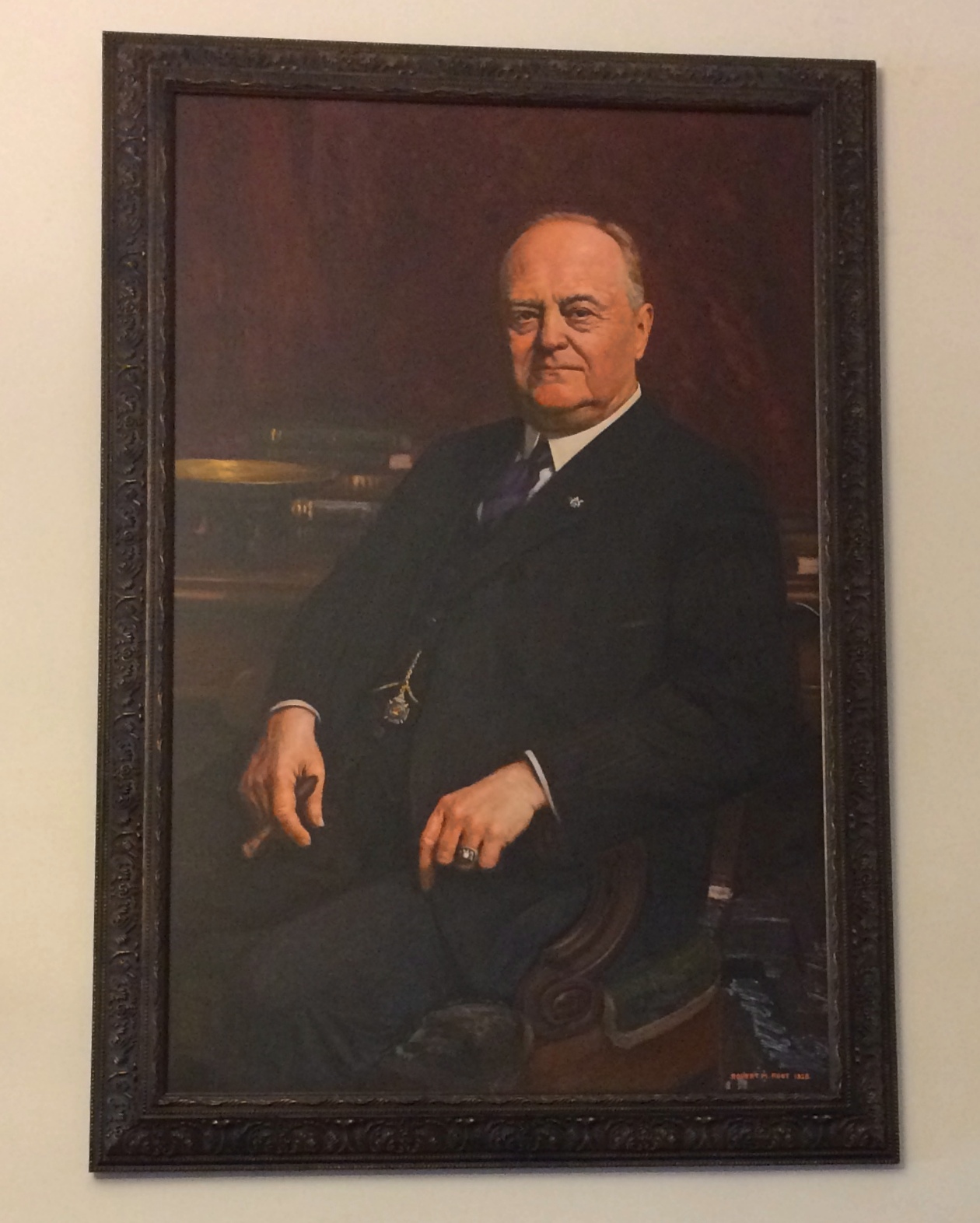

Here’s the boss man himself.

Looking every bit the ’20s tycoon. He also developed an office building for his company a few miles from the home. The structure was one of the largest things in Decatur at the time, and a stylish ’20s design it is (see page 5).

Looking every bit the ’20s tycoon. He also developed an office building for his company a few miles from the home. The structure was one of the largest things in Decatur at the time, and a stylish ’20s design it is (see page 5).

Later in the day, we drove by for a look at the office building from the street. It’s still a commanding presence in its part of Decatur, though like the A.E. Staley Mfg. Co., it’s part of Tate & Lyle, a British supplier of food and beverage ingredients to industrial markets.

In 2014, I took note of Plensa’s monumental head, temporarily placed in Millennium Park in Chicago, “Looking Into My Dreams, Awilda.” I also knew at the time that the Catalan artist had also done Crown Fountain in the park as well.

In 2014, I took note of Plensa’s monumental head, temporarily placed in Millennium Park in Chicago, “Looking Into My Dreams, Awilda.” I also knew at the time that the Catalan artist had also done Crown Fountain in the park as well.

“Self Portrait With Tree,” by none other than Plensa. I’d forgotten about it, and when I took the picture, probably didn’t associate it with the other works of his I’d seen. “Self Portrait” was next to the Hancock Tower on E. Chestnut St. I checked the Street View of that block, dated July 2018, and the work is gone. It was put up by the nearby Richard Gray Gallery, so perhaps it found a buyer.

“Self Portrait With Tree,” by none other than Plensa. I’d forgotten about it, and when I took the picture, probably didn’t associate it with the other works of his I’d seen. “Self Portrait” was next to the Hancock Tower on E. Chestnut St. I checked the Street View of that block, dated July 2018, and the work is gone. It was put up by the nearby Richard Gray Gallery, so perhaps it found a buyer.

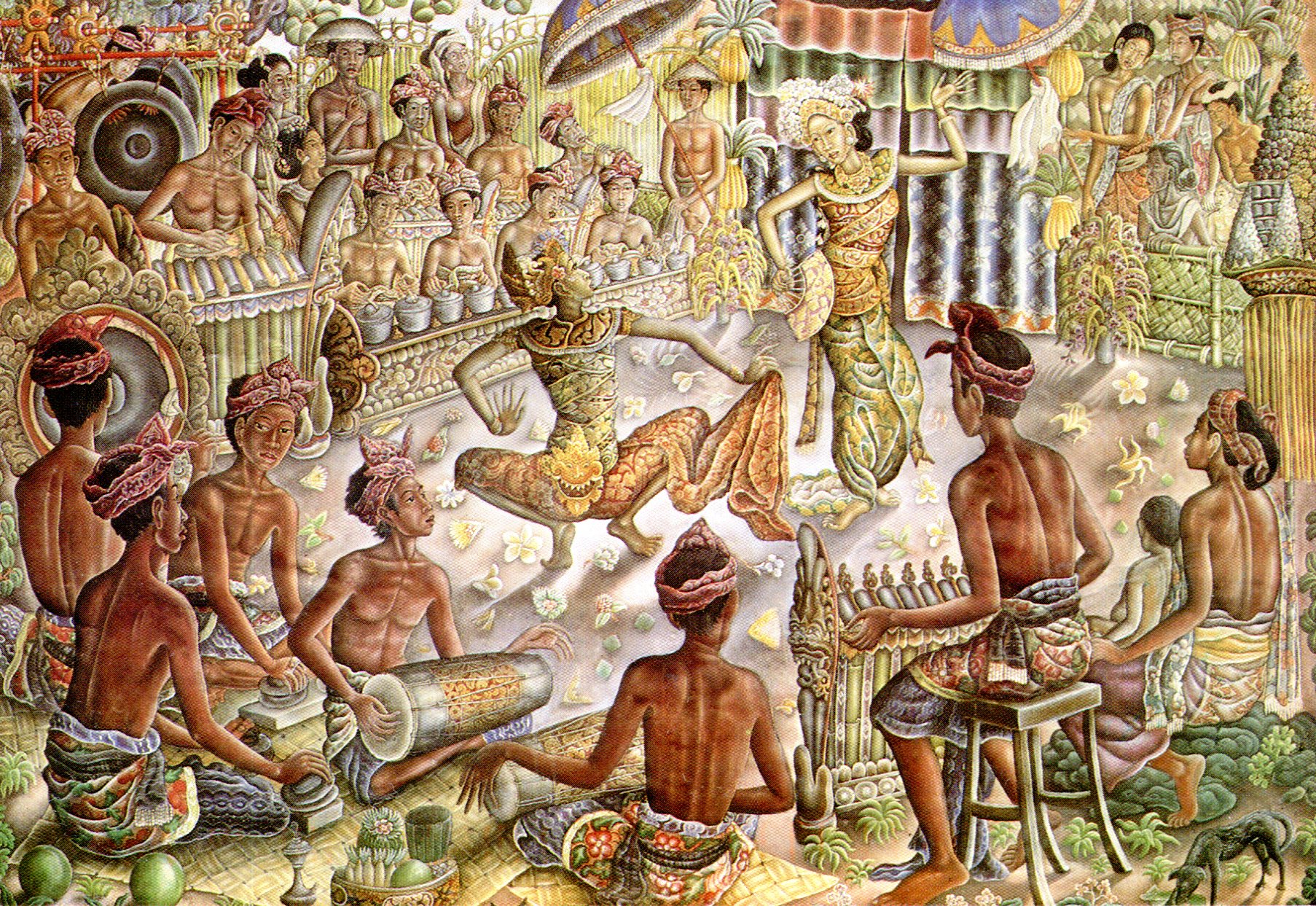

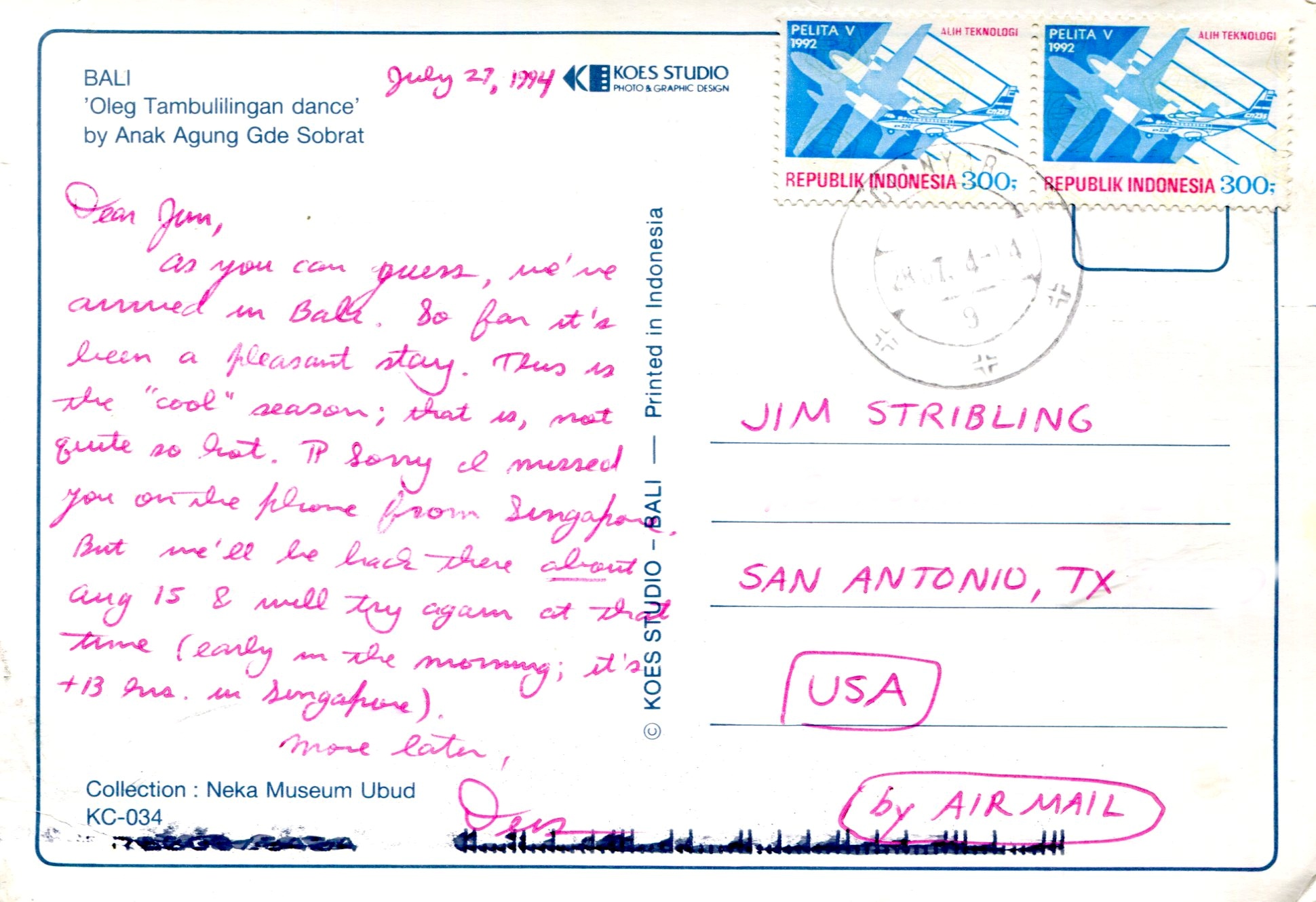

A lively, colorful work by

A lively, colorful work by  The Neka Museum in Ubud, now known as the

The Neka Museum in Ubud, now known as the