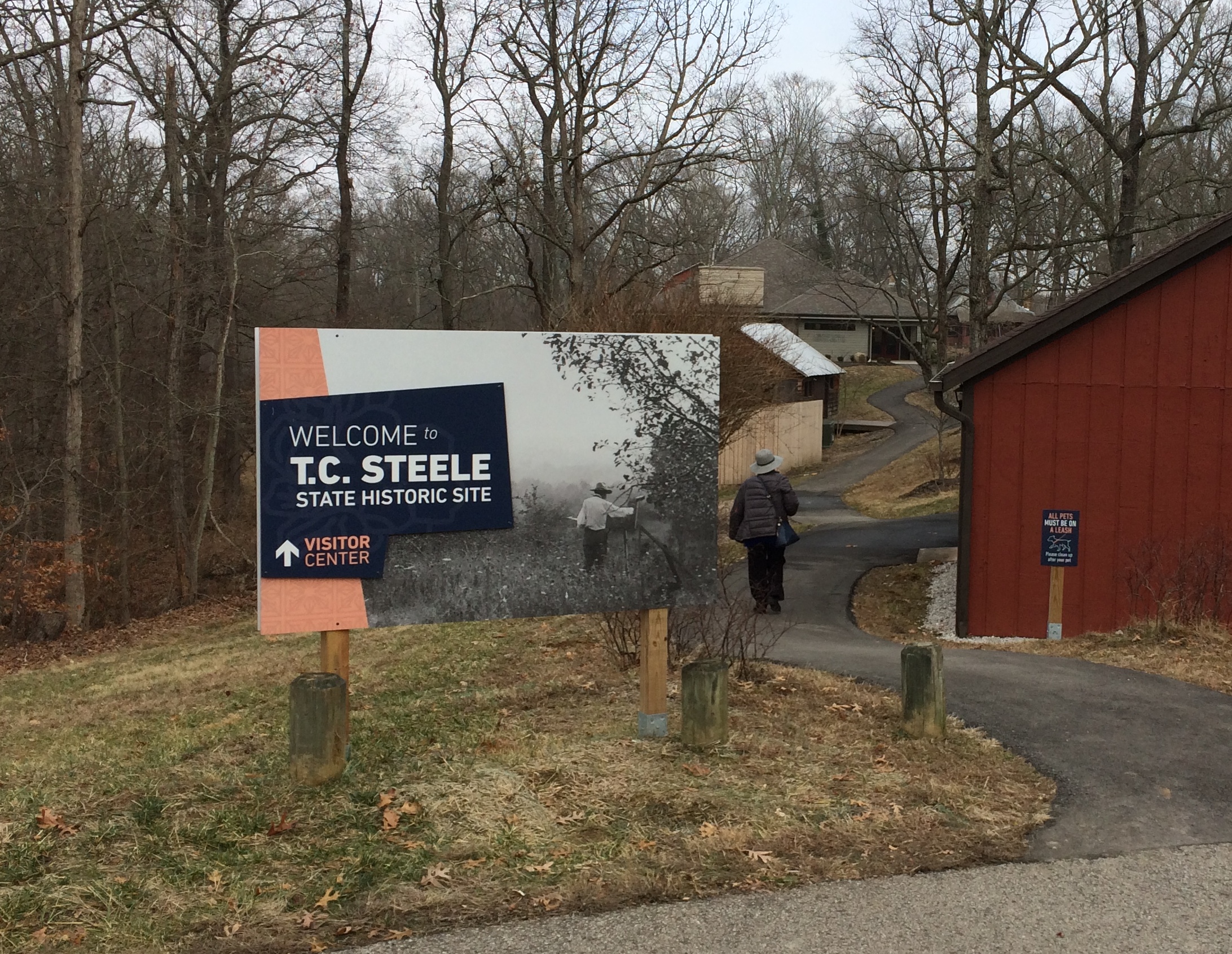

Tibetan-style structures and T.C. Steele’s property and all the other places we saw in southern Indiana near the end of December were worth seeing, but none were the main reason we went down that way.

That would be the West Baden Springs Hotel, one of the grand old hotels of the nation, revived in our time to an astonishing degree. Magnificent as the Hotel del Coronado or the Waldorf-Astoria, historic as the Fordyce at Hot Springs National Park or the Boca Raton Resort & Club.

We drove south from Bloomington in intermittent rain on the morning of December 29 to the town of West Baden, in Orange County, Indiana, an otherwise rural place with a county population of a shade less than 20,000. The hotel was impossible to miss driving into town. Even at some distance, it cuts an impressive figure.

More so closer in.

There’s been a hotel on the site since 1855, at first called the Mile Lick Inn. Why in this obscure part of Indiana? The waters, of course. Indians knew about the springs and so did Frenchmen, who lent their national name to the nearby French Lick Springs Hotel, about a mile from the West Baden Springs Hotel.

There’s been a hotel on the site since 1855, at first called the Mile Lick Inn. Why in this obscure part of Indiana? The waters, of course. Indians knew about the springs and so did Frenchmen, who lent their national name to the nearby French Lick Springs Hotel, about a mile from the West Baden Springs Hotel.

Eventually a branding impulse kicked in, and Mile Lick became West Baden Springs, to capture some of the Victorian cachet of Baden-Baden in Germany, where the Euro-elite took the waters. I learned pretty quickly, by the way, that the Hoosier way to say the name is West BAY-den, not BAA-den.

The original West Baden Springs burned down just after the turn of the 20th century. The owner, Lee W. Sinclair, wanted something even grander replace it — something to best the rival French Lick Springs Hotel — and so he built the current hotel.

“Sinclair… envisioned a circular building topped with the world’s largest dome, decorated like the grandest spas of Europe,” notes the hotel web site. “Architect Harrison Albright of West Virginia [who designed the U.S. Grant Hotel in San Diego, too] accepted Sinclair’s commission and agreed to complete the project within a year. The new hotel, complete with a 200-foot diameter atrium and fireplace that burned 14-foot logs, opened for business in June of 1902.”

Later, Sinclair’s daughter and son-in-law redesigned the hotel a new level of opulence in the ’20s that characterized West Baden Springs Hotel until the Depression crushed its business model. The rest of the 20th century was unkind to the property, especially the last years of the century.

“In January 1991, a buildup of ice and water on the roof and in drainpipes caused the collapse of a portion of the exterior wall,” the web site says. “In 1992, Indiana Landmarks spent $140,000 to stabilize the hotel, matching a $70,000 contribution from an anonymous donor. In May 1994 the hotel was sold to Minnesota Investment Partners (MIP) for $500,000. Grand Casinos Inc., an investor in the purchase, optioned the hotel from MIP. The Cook Group Inc., a global medical device manufacturing company headquartered nearby in Bloomington, stepped in to preserve both the French Lick and West Baden Springs Hotels.”

That is to say, the Cook family — medical-device billionaires — took an interest in the place. Eventually they oversaw the renovation of West Baden Springs, as well as French Lick Springs, at great expense. But not without what I imagine must be a healthy return, now that a major new Cook-owned casino (next to French Lick Springs) is open for business. All of the properties (West Baden Springs, French Lick Springs and the new casino) are part of the French Lick Resort Casino, an operation licensed by the state of Indiana in 2006.

I’ve read variously that the West Baden Springs Hotel dome was the nation’s largest freestanding structure of its kind until the completion of the Charlotte Coliseum in 1955 or the Astrodome in 1965. Whatever the case, the thing to do in our time is wander into the hotel atrium, stand under the dome, and be amazed. Ordinary photos can’t convey the sweep of the place or the its grand scope, but never mind.

Other parts of the hotel have their own flourishes, such as the stained-glass windows near the front entrance, added by Jesuits when they owned the property in the mid-century. Quite a story.

Other parts of the hotel have their own flourishes, such as the stained-glass windows near the front entrance, added by Jesuits when they owned the property in the mid-century. Quite a story.

We rode a trolley over to French Lick Springs for a look. Posh, certainly, and also a historic hotel — that’s where Pluto Water used to come from, and walls are covered with glossy pics of famous guests — but it’s only worth seeing, not worth going to see, like West Baden Springs is.

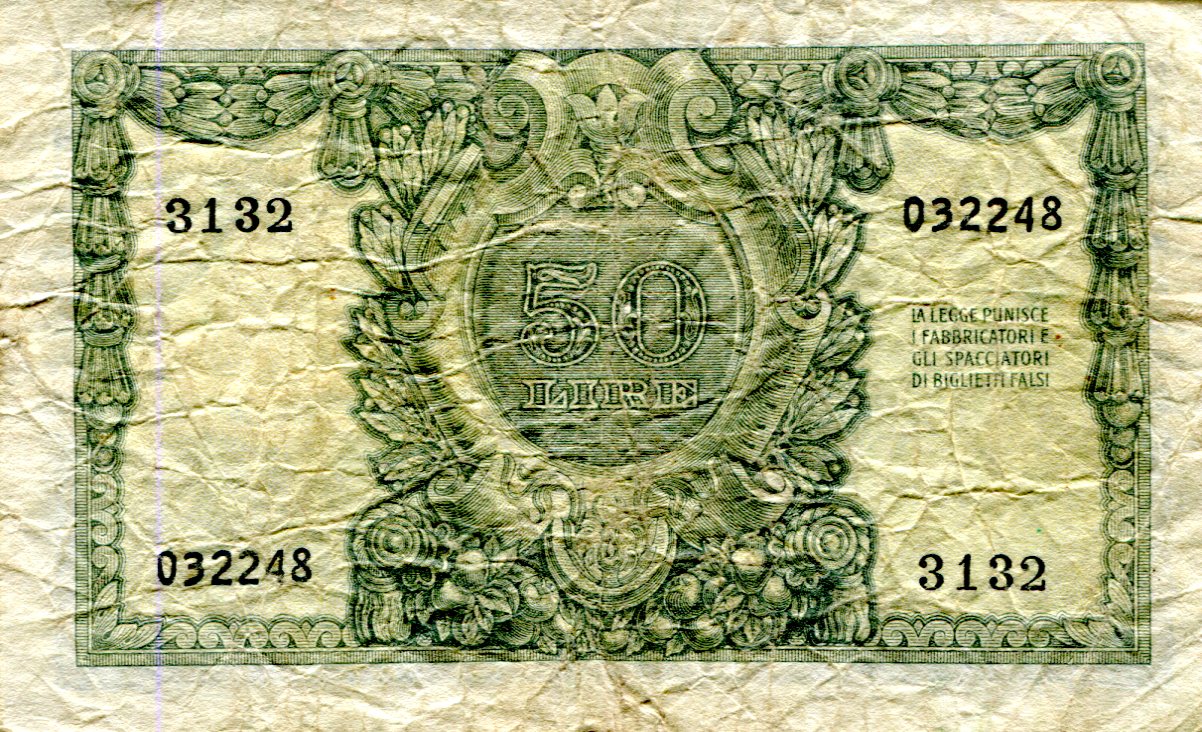

Italy, 1951. Small in value — 50 lira, or the equivalent of about 8 U.S. cents, at least as of the mid-50s, which is when my parents picked it up in change. Must adjust for inflation, however, so theoretically in today’s money that many lira is the equivalent of a whopping 75 U.S. cents, or about 0.68 euros. Apparently this note and the 100-lira were replaced by coins not much later in the 1950s.

Italy, 1951. Small in value — 50 lira, or the equivalent of about 8 U.S. cents, at least as of the mid-50s, which is when my parents picked it up in change. Must adjust for inflation, however, so theoretically in today’s money that many lira is the equivalent of a whopping 75 U.S. cents, or about 0.68 euros. Apparently this note and the 100-lira were replaced by coins not much later in the 1950s. The note is also small in size. Interestingly, exactly four inches long and two-and-a-half inches tall. Odd, I would have thought that the sides measure evenly in centimeters rather than inches.

The note is also small in size. Interestingly, exactly four inches long and two-and-a-half inches tall. Odd, I would have thought that the sides measure evenly in centimeters rather than inches. Who are these gentlemen who look so much alike, except the eyes of one are closer together than the other?

Who are these gentlemen who look so much alike, except the eyes of one are closer together than the other?

In a poetic touch, the Steeles named their place The House of the Singing Winds. Our visit wasn’t on a windy day, so that isn’t what we heard out on the hillside. Rather, the crunching of leaves underfoot. Without the sound of traffic coming from all directions, and with birds and insects quiet or gone for the season, that was about all we heard. That by itself was a good reason to get out of town.

In a poetic touch, the Steeles named their place The House of the Singing Winds. Our visit wasn’t on a windy day, so that isn’t what we heard out on the hillside. Rather, the crunching of leaves underfoot. Without the sound of traffic coming from all directions, and with birds and insects quiet or gone for the season, that was about all we heard. That by itself was a good reason to get out of town.