One of the things I wanted to do between Christmas and New Year was visit one of Chicago’s lesser-known museums, ideally one I hadn’t gotten around to. So I went to the Pritzker Military Museum & Library, which is on second and third floors of 104 S. Michigan Ave., overlooking Millennium Park.

Pritzker, as in the Chicago family of billionaires, the architecture prize, and the incoming governor of Illinois. In particular, the museum is a project of retired Col. Jennifer (formerly James) Pritzker of the Illinois Army National Guard, who was also in the U.S. Army for a good many years.

Pritzker, as in the Chicago family of billionaires, the architecture prize, and the incoming governor of Illinois. In particular, the museum is a project of retired Col. Jennifer (formerly James) Pritzker of the Illinois Army National Guard, who was also in the U.S. Army for a good many years.

All of the display space — a few rooms on the two floors — is currently given over to the Great War. Fittingly. On display are photos, posters and items carried by WWI soldiers.

There are also a few less conventional items to see.

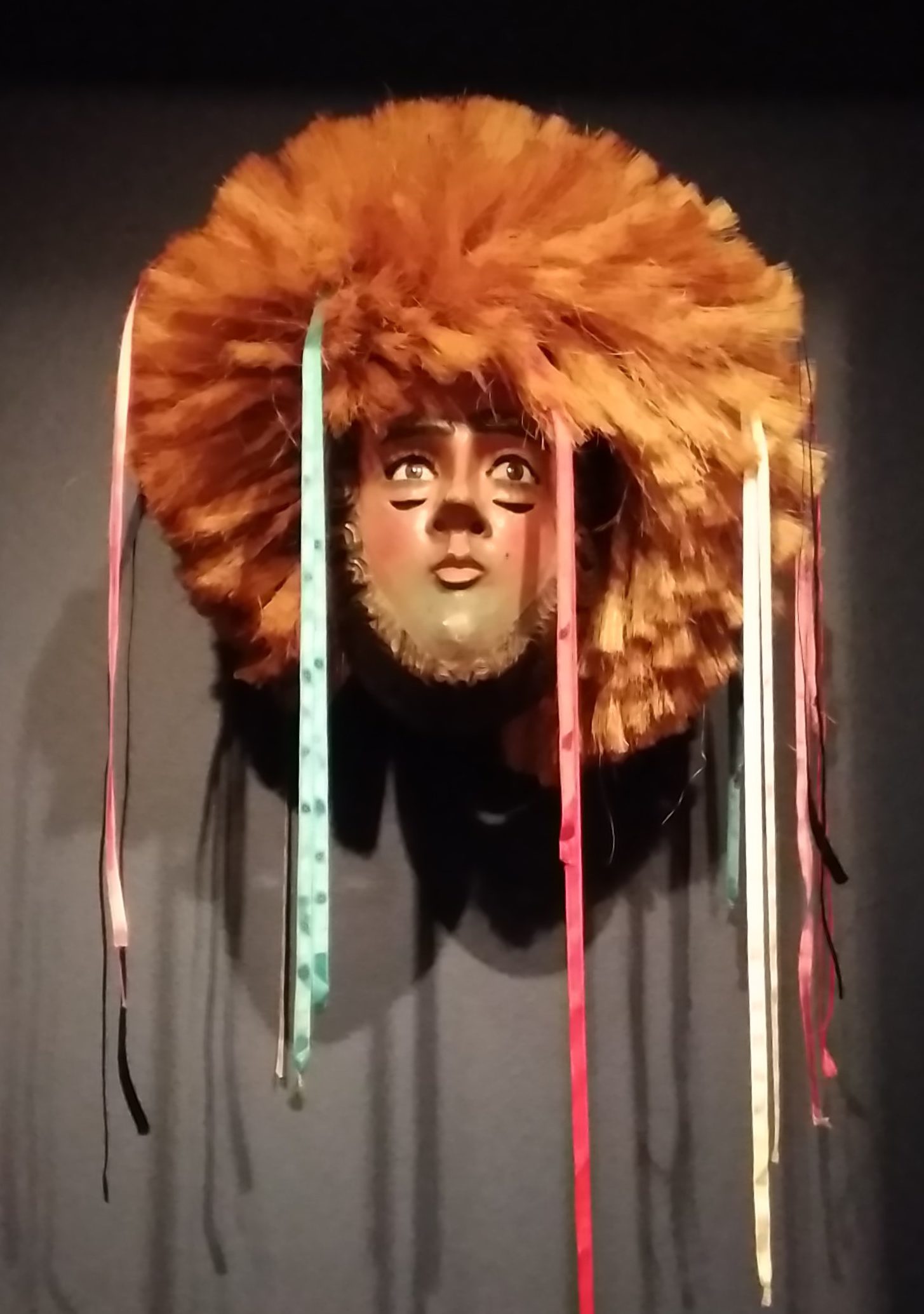

Nothing says Great War like a papier-mâché Kaiser head. According to the sign, “A mask like this one… might have been worn on a float or during a play as a way to mock the German monarch.”

Nothing says Great War like a papier-mâché Kaiser head. According to the sign, “A mask like this one… might have been worn on a float or during a play as a way to mock the German monarch.”

No doubt. What I wonder is how the thing survived 100 years. When the initial fun of Kaiser-mocking died down, did its creator tuck it away in some attic, only to be forgotten for decades? I can imagine some grandson or granddaughter cleaning out that attic in, say, the 1970s, and saying, “What is this? Let’s get rid of it.” But that didn’t happen. Somehow the Kaiser head made its way to the Pritzker, founded only in 2003.

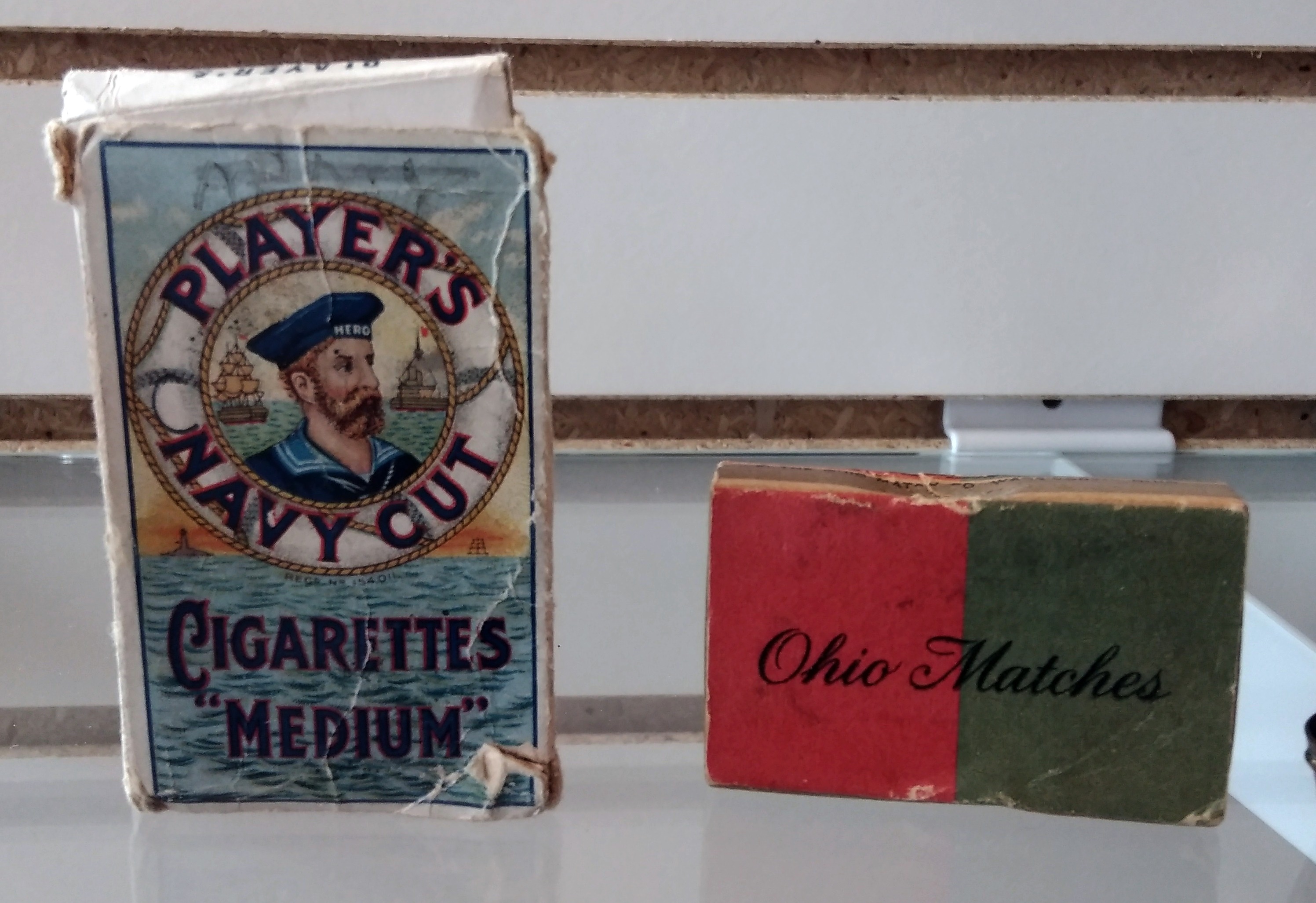

What could be more important to Great War soldiers and sailors than their cigs?

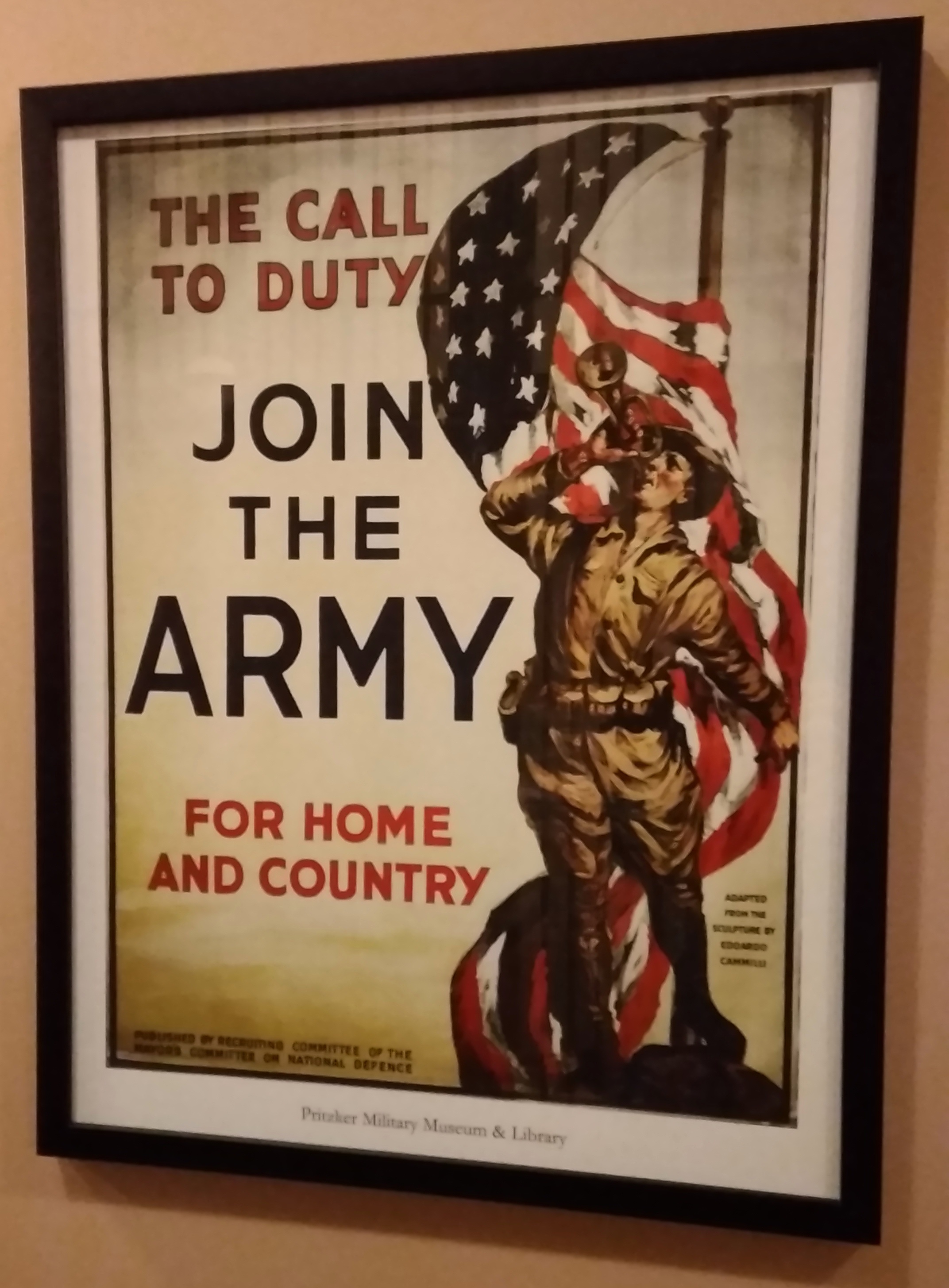

I was especially taken with the collection of posters. Some as conventional as can be.

I was especially taken with the collection of posters. Some as conventional as can be.

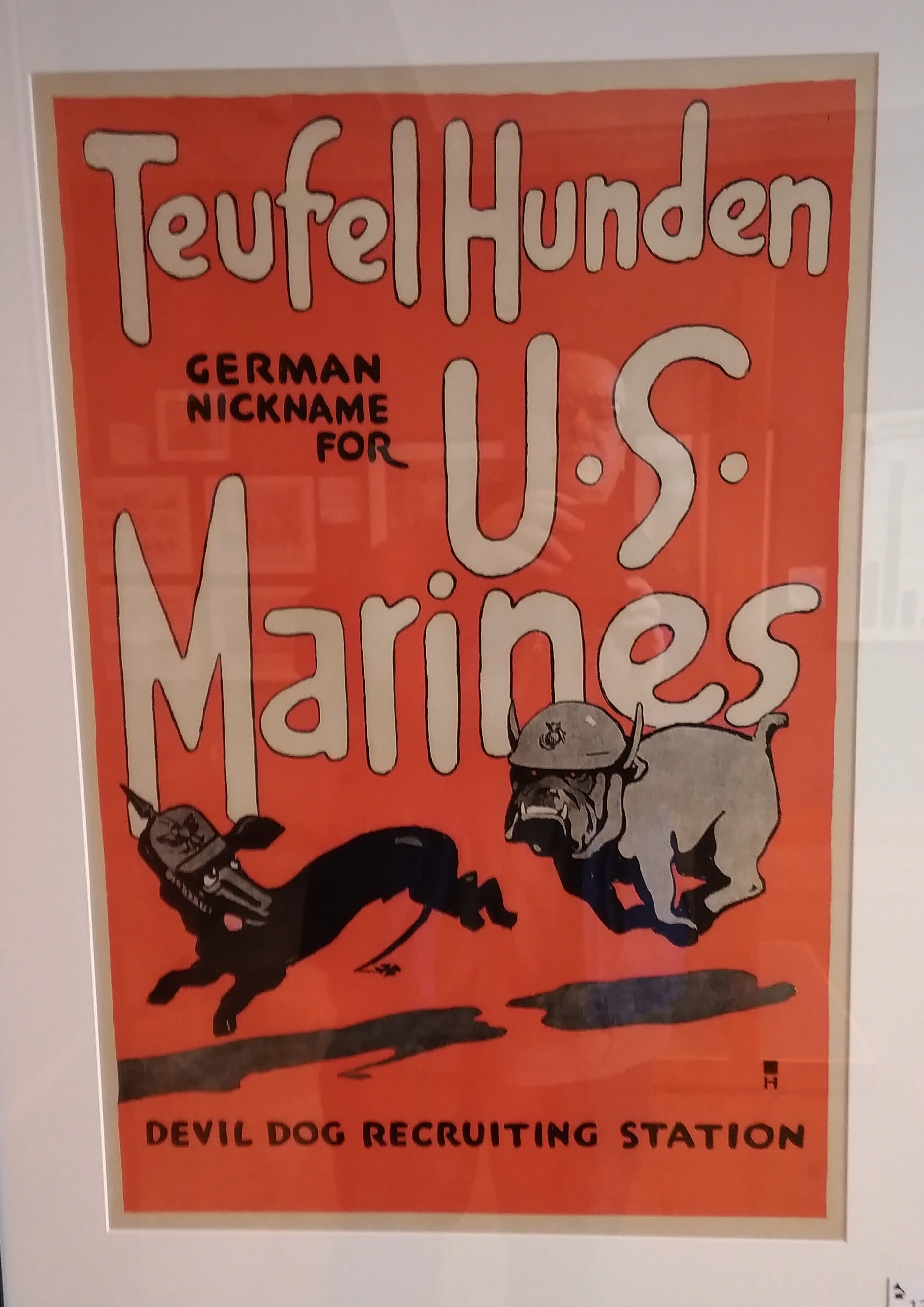

Some more whimsical.

Some more whimsical.

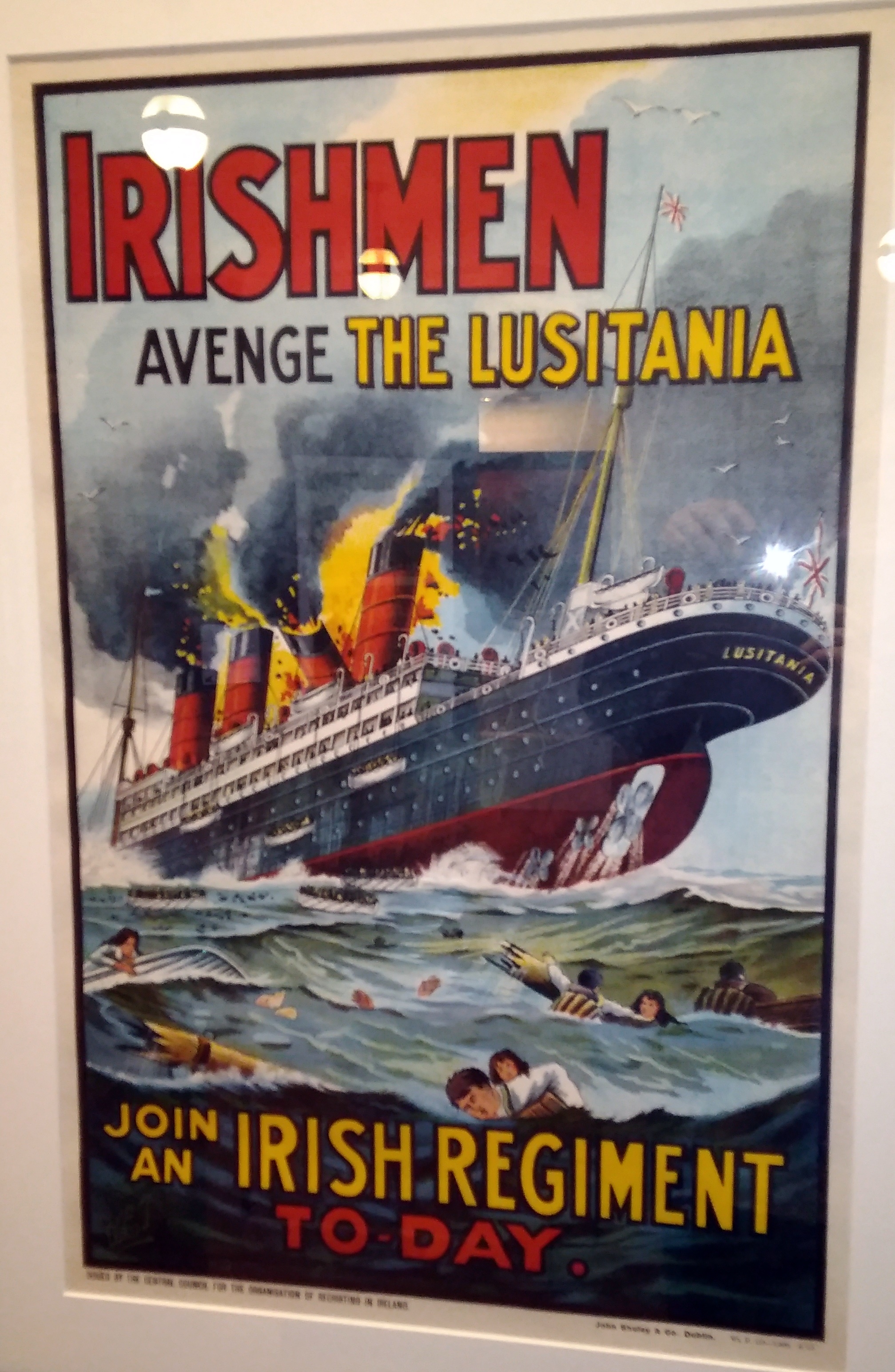

One appealing to ethnic pride and righteous outrage at the same time.

One appealing to ethnic pride and righteous outrage at the same time.

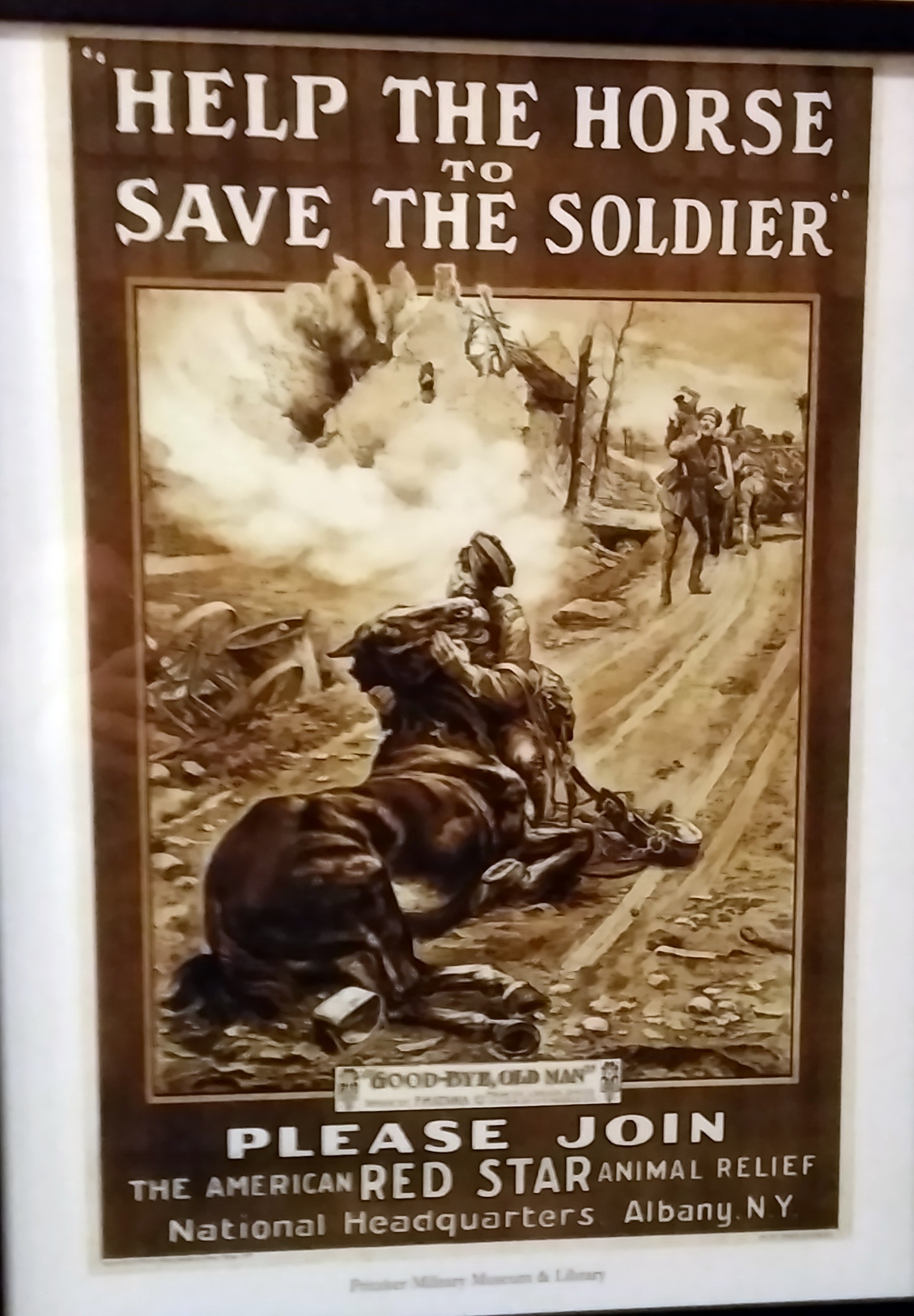

This was for an organization essentially lost to time, though in fact the American Red Star Animal Relief Program is still around, now called Animal Emergency Services.

This was for an organization essentially lost to time, though in fact the American Red Star Animal Relief Program is still around, now called Animal Emergency Services.

“[In WWI] the U.S. armed services used 243,135 horses and mules during the war to transport supply wagons, ambulances, traveling kitchens, water carts, food, engineer equipment, light artillery, and tons of shells. Horses were used in direct combat as well,” American Humane says.

“[In WWI] the U.S. armed services used 243,135 horses and mules during the war to transport supply wagons, ambulances, traveling kitchens, water carts, food, engineer equipment, light artillery, and tons of shells. Horses were used in direct combat as well,” American Humane says.

“American Humane sent medical supplies, bandages, and ambulances to the front lines to care for the injured horses — an estimated 68,000 per month.

“Since that time, American Humane has helped the animal victims of natural and manmade disasters, such as floods, chemical spills, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, and victims of animal cruelty throughout the country.”

The John C. Smith House, 1907 American Four Square. That’s a nice porch.

The John C. Smith House, 1907 American Four Square. That’s a nice porch.

Not the best view of the house. That would be

Not the best view of the house. That would be

This aircraft isn’t the one Bong flew. While he was stateside, it crashed while another pilot was flying it. The Army took delivery of the one on display in July 1945, after Bong had been ordered to quit flying combat missions. The Richard I. Bong American Legion Post of Poplar, Wis., acquired the plane from the Air Force in 1949, and it was on display in that town for some decades.

This aircraft isn’t the one Bong flew. While he was stateside, it crashed while another pilot was flying it. The Army took delivery of the one on display in July 1945, after Bong had been ordered to quit flying combat missions. The Richard I. Bong American Legion Post of Poplar, Wis., acquired the plane from the Air Force in 1949, and it was on display in that town for some decades.

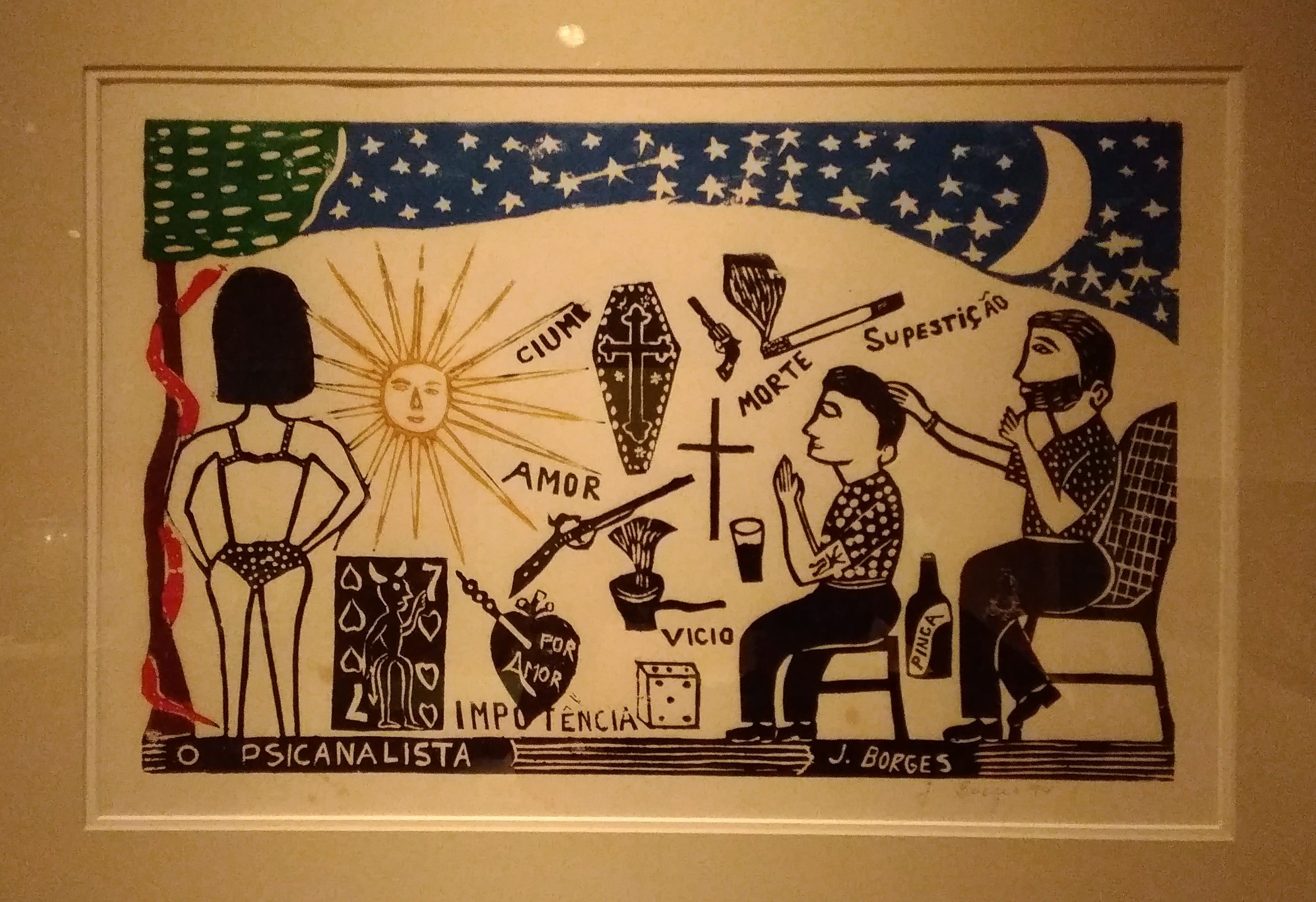

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.

“Bird Woman” (2001) by

“Bird Woman” (2001) by