On Tuesdays, the Briscoe Western Art Museum in downtown San Antonio — in full, the Dolph and Janey Briscoe Western Art Museum — offers free admission from 4 to 9 p.m., so after wrapping up my work that day last week, I decided to visit within that window of discount opportunity. It’s still a fairly new museum, open only since 2013, so I’d never been.

The building, which is on W. Market St., is not new. It was the main city library from 1930 to 1968, so I don’t remember it as that, though my mother and grandparents would have known it.

The lobby is striking. This image was taken before the installation of a reception desk toward the back, and a large bronze, John Coleman’s “Visions of Change.” A lot of restoration apparently went into bringing the interior roughly back to its library-era look.

The lobby is striking. This image was taken before the installation of a reception desk toward the back, and a large bronze, John Coleman’s “Visions of Change.” A lot of restoration apparently went into bringing the interior roughly back to its library-era look.

For some decades after the library moved, the building housed the Hertzberg Circus Collection, an enormous array of circus artifacts that the library used to own. That I remember. Vaguely. I know I went once as a kid. Around the beginning of the 21st century, the Witte Museum acquired the collection and plans were laid for the current museum.

Something like the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, the Briscoe focuses on art from both the Indian and non-Indian populations of the West, but it also has a lot of artifacts. In nine galleries on three levels, that includes paintings, sculptures, guns and other weapons, such as a fancy sword owned by Santa Anna, saddles — Pancho Villa’s and Roy Rogers’ — jewelry, Mexican santos and retablos, a chuck wagon, a replica stage coach, and a collection of spurs that takes up an entire wall.

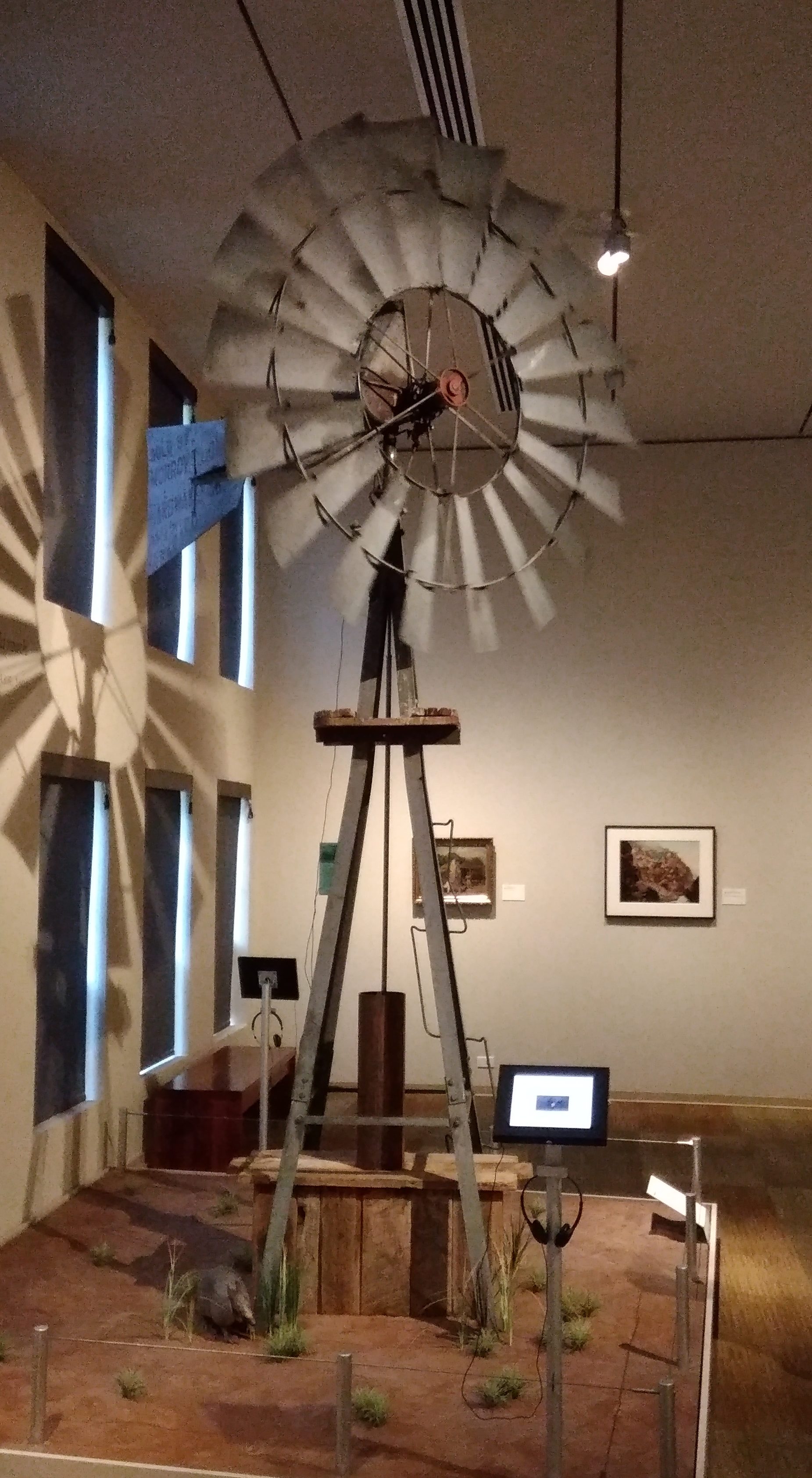

There are some Texas touches, such as a windmill in motion. Other Western states have them, but windmills have a special place in the history of Texas.

There’s a de facto shrine to Dolf and Janey Briscoe in the form of Dolf’s desk and some other items. As you’d expect, the Briscoes donated art and ponied up money to make the museum possible.

Good old Dolf. I think of him as a mellow governor, as befitting his ’70s time in office. I’m sure that’s nonsense, though: you don’t get to be a successful politico, much less governor of a large state, by being mellow. Not even if you start out as one of the richest men in the state. Rich in a traditional Texas way, too: a vast ranching operation. None of this microchip or cyber-fortune wealth for Dolf (well, maybe he branched into all that before he died in 2010).

Good old Dolf. I think of him as a mellow governor, as befitting his ’70s time in office. I’m sure that’s nonsense, though: you don’t get to be a successful politico, much less governor of a large state, by being mellow. Not even if you start out as one of the richest men in the state. Rich in a traditional Texas way, too: a vast ranching operation. None of this microchip or cyber-fortune wealth for Dolf (well, maybe he branched into all that before he died in 2010).

My own favorite item in the museum: a large diorama behind glass walls depicting the storming of the Alamo. Carelessly, I didn’t check to see who created it, though it might be the work of one Tom Feeley. The museum’s web site is unhelpful in telling me. But whoever it was did a first-rate job.

The diorama includes all of the walls standing at the time of the siege, plus the buildings, and thousands of two- or so inch figures — armed Mexicans and Texians, horses, cannons — all done with incredible attention to detail. It captures the moment when the defenders, surrounded on all four sides by masses of Mexican soldiers, are about to be overwhelmed; but they’re still fighting.

Headphones are attached to a low wall below the glass, and you can listen to short items about various participants in the battle — the big three of Travis, Crockett and Bowie, of course, but also Susanna Dickinson, Joe (Travis’ slave), Gen. Cos and Santa Anna.

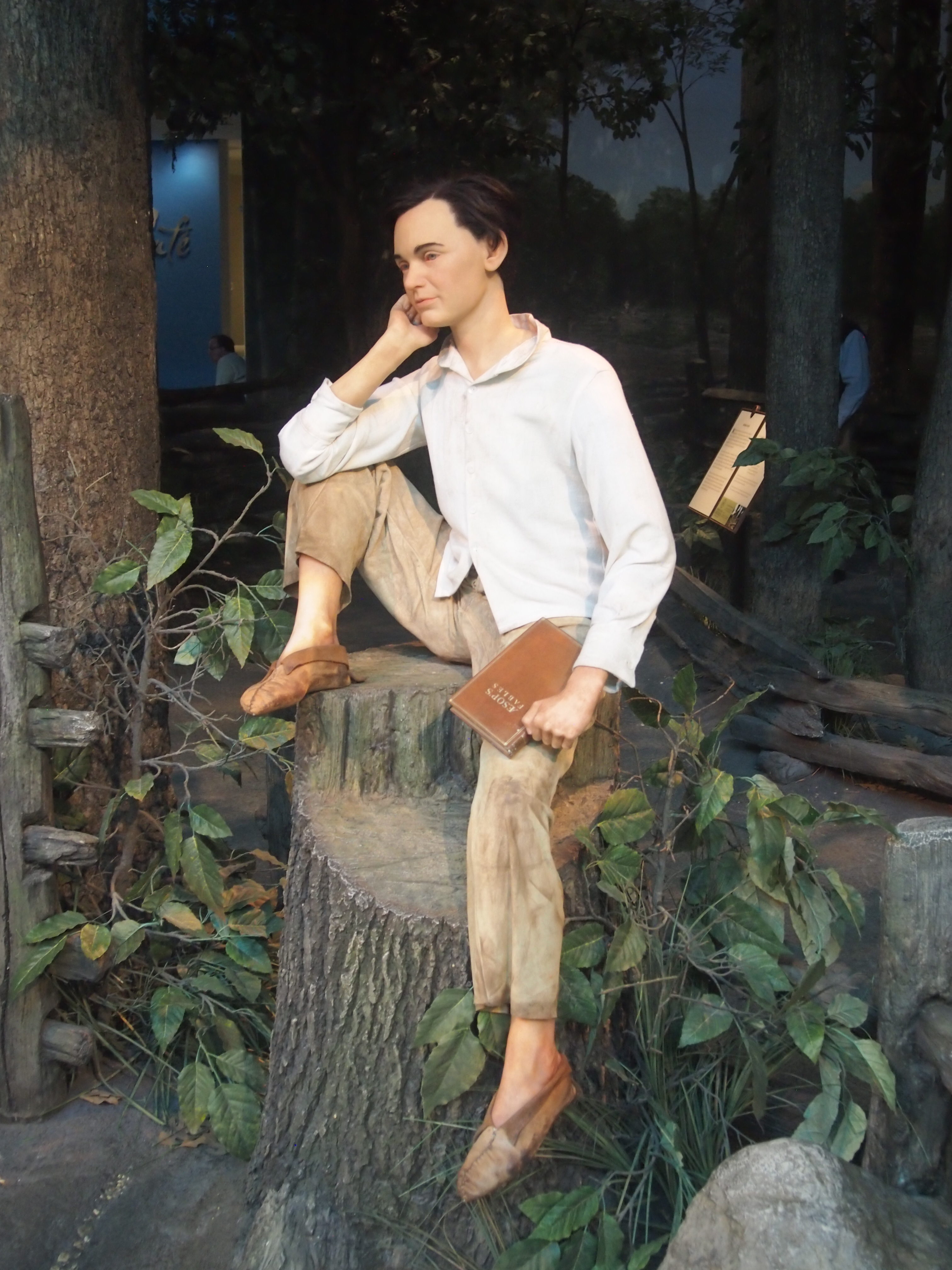

Near the diorama is a life-sized bronze of Travis, “Col. Travis — The Line” by James Muir, who specializes in heroic and allegorical work. That is, it depicts Travis drawing his famed line in the sand. A se non è vero, è ben trovato sort of story if there ever was one.

The artists in the museum’s temporary exhibit were a little unexpected: Andy Warhol and Billy Schenck. The Warhol part of the exhibit is very late Warhol (he died the next year): his 1986 Cowboys & Indians series. The artist gave his colorful and instantly recognizable treatment to the likes of John Wayne, Annie Oakley, George Custer, Geronimo and TR, among others.

Warhol might have been at risk, in earlier decades, of being a hopelessly dated artist, one whose reputation is forever stuck in the 1960s. Somehow he seems to have avoided that.

I’m less familar with Billy Schenck, who, unlike Warhol, is still alive and working. He’s “Warhol of the West,” according to the museum, and there are some similarities, especially in his generous displays of color. On the whole, he’s a match for Warhol. His work on exhibit at the Briscoe includes a number of the pieces in the slideshow at his web site.

The museum says, ” Built in 1913, this ‘menagerie’ carousel’s hand-carved animals include storks, goats, zebras, dogs, and even a frog. Although its original location is uncertain, this carousel operated in Spokane, Washington, from 1923 to 1961.”

The museum says, ” Built in 1913, this ‘menagerie’ carousel’s hand-carved animals include storks, goats, zebras, dogs, and even a frog. Although its original location is uncertain, this carousel operated in Spokane, Washington, from 1923 to 1961.”