World War II was a big war, and it has an impressively big museum in New Orleans, the National WW II Museum, which we visited on May 14. The focus isn’t the whole — that’s too big — but rather the American part in the global conflict. A big enough subject.

All together, the museum includes five buildings of more than one story each, artifacts large and small, a vast number of words to read with the exhibits, and dozens of continuous video presentations.

The building reminded me a bit of the Denver Art Museum’s Hamilton Building, but a different architect did the work, Bart Voorsanger.

The structure isn’t finished yet. Looks like the wing-like-thing (wing of victory?) is being added right now.

A museum of this scope is exhaustive and exhausting, but I’m getting old. It has a lot of ground to cover, of course, but more than that the museum needs heft to amplify the war’s increasingly dim echo as time passes. It’s mostly vanished from living memory.

The Second World War was my parents’ war, so when I was growing up, the echo was pretty loud, largely in the torrent of books and movies and TV shows dealing with the war. Some of my earliest memories of watching TV include Combat! and The Rat Patrol, to use examples of televised WWII fiction more and less serious. The details of the war might have faded some by the time I came along — it was years before I got Bugs Bunny’s joke about A cards at the end of “Falling Hare” — but the big picture was still clear.

Time passes, even the big picture fades. Just look at what has happened to the Great War. It’s all we can do that they shall not grow old.

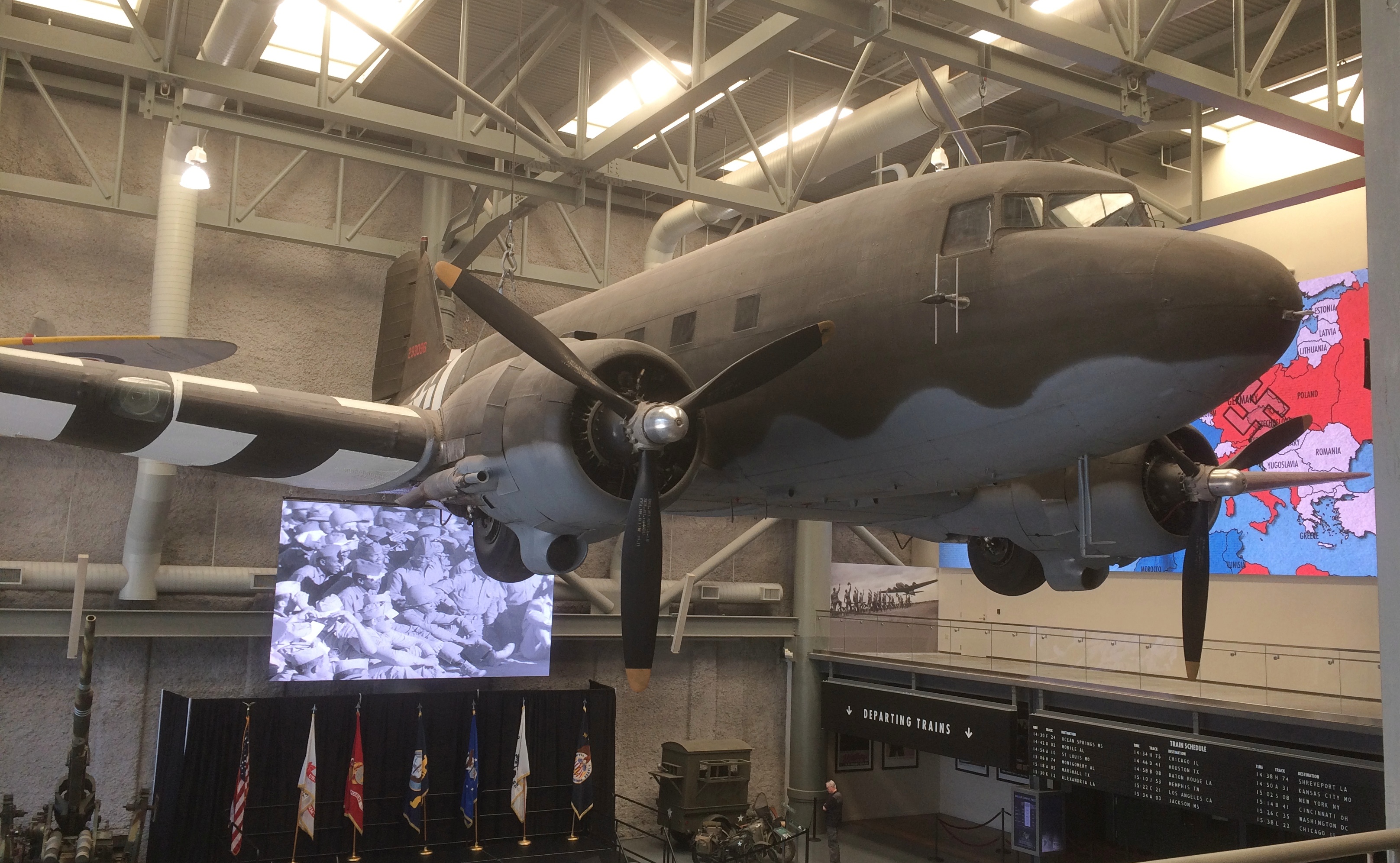

So the National WWII Museum starts off big, with a Douglas C-47 Skytrain hanging from the ceiling over the entrance and ticketing counter, which is in the Louisiana Memorial Pavilion.

On the floor is a replica LCVP, built from original plans. This kind of boat is pretty much the reason the museum is in New Orleans.

On the floor is a replica LCVP, built from original plans. This kind of boat is pretty much the reason the museum is in New Orleans.

As an acronym, LCVP is about as standard Army as you can get: “landing craft, vehicle, personnel.” Less formally, they’re Higgins boats, designed by Andrew Higgins and built en masse during the war by Higgins Industries of New Orleans.

As an acronym, LCVP is about as standard Army as you can get: “landing craft, vehicle, personnel.” Less formally, they’re Higgins boats, designed by Andrew Higgins and built en masse during the war by Higgins Industries of New Orleans.

Wiki describes the usefulness of the boats well: “The Higgins boat was used for many amphibious landings, including Operation Overlord on D-Day in Nazi German-occupied Normandy, and previously Operation Torch in North Africa, the Allied invasion of Sicily, Operation Shingle and Operation Avalanche in Italy, Operation Dragoon, as well as in the Pacific Theatre at the Battle of Guadalcanal, the Battle of Tarawa, the Battle of the Philippines, the Battle of Iwo Jima and the Battle of Okinawa.”

Pretty much a greatest hits of U.S. amphibious landings during the war. In its early days, beginning in 2000, the museum focused on D-Day exclusively, so what better place than the city where the Higgins boats were built?

Upstairs in the Louisiana Memorial Pavilion is a floor devoted to the U.S. industrial production so critical to victory. As the museum notes, “By the time the Japanese surrendered in 1945… American manufacturers had turned out more than 96,000 bombers, 86,000 tanks, 2.4 million trucks, 6.5 million rifles, and billions of dollars’ worth of supplies to equip a truly global fighting force.”

A number of artifacts illustrate the Arsenal of Democracy, such as a jeep chassis.

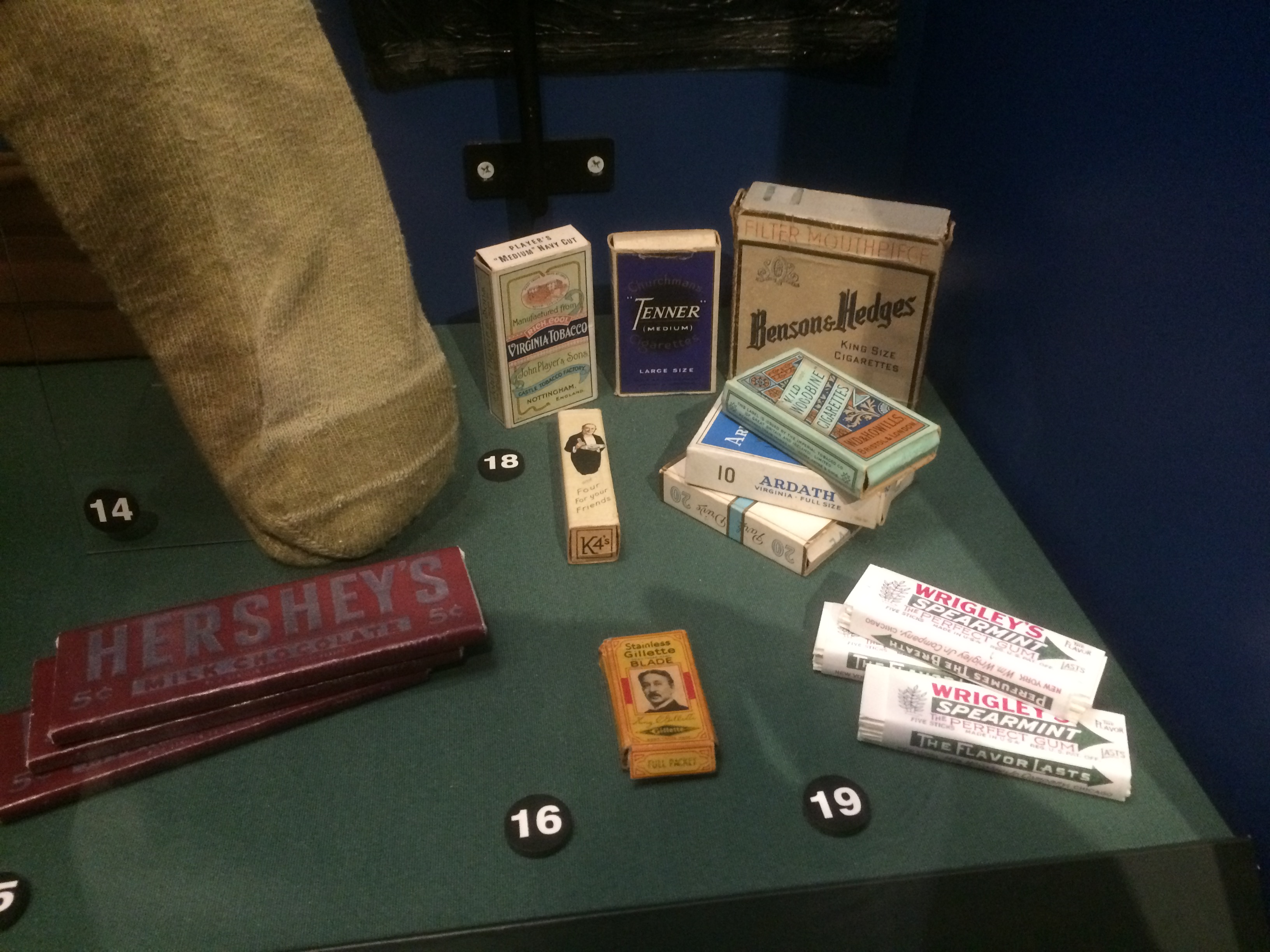

Along with smaller items, such as the cigarettes, chocolate and gum that made a soldier’s lot slightly more bearable.

Along with smaller items, such as the cigarettes, chocolate and gum that made a soldier’s lot slightly more bearable.

A machine to make dog tags.

A machine to make dog tags.

They actually were an innovation just before WWI, at least as far as Americans were concerned. For millennia, many men went off to war and simply vanished. I remember, for instance, seeing at Gettysburg National Cemetery row upon row of stones marked UNKNOWN.

They actually were an innovation just before WWI, at least as far as Americans were concerned. For millennia, many men went off to war and simply vanished. I remember, for instance, seeing at Gettysburg National Cemetery row upon row of stones marked UNKNOWN.

Also in the Louisiana Memorial Pavilion is the D-Day exhibit. As the original crux of the museum, it’s very detailed, with artifacts, images, reading material and more. The rooms reminded me of the Musée du Débarquement Arromanches in Normandy, though that facility had the advantage of looking out on the remains of one of the artificial harbors used during the landing.

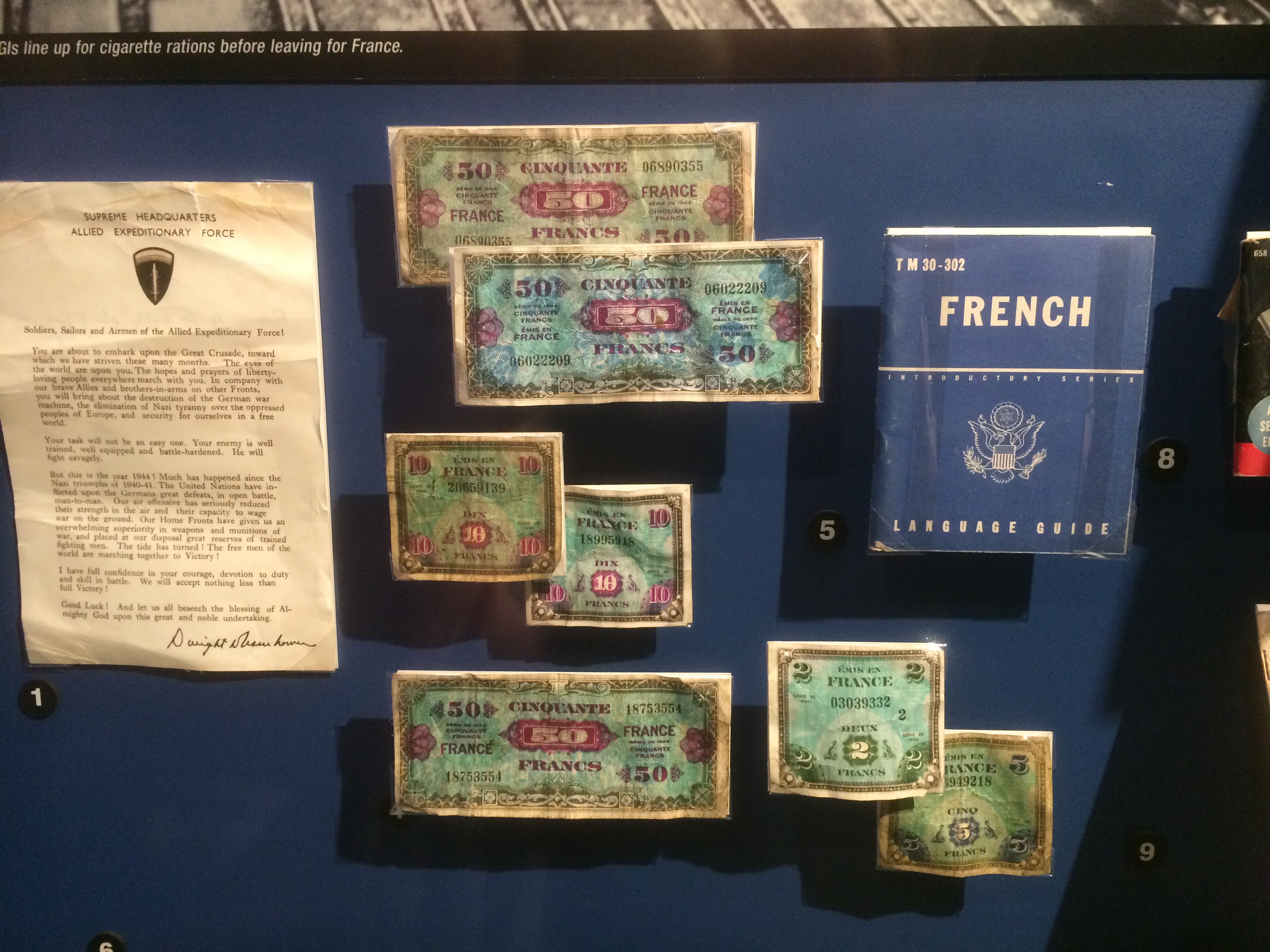

A copy of the Order of the Day, June 6, 1944, along with French currency presumably carried by soldiers. Notes, not coins.

Another building, Campaigns of Courage, highlights the course of the war in the European and Pacific theaters with artifacts, photos, movies, text and some elaborate diorama-like sections that visitors walk through.

In Europe, for example, the Seige of Bastogne, done to look like snowy woods, though without the freezing temps. In the Pacific, the Guadalcanal Campaign, done to look like a tropical rain forest, though without the venomous bugs. There’s only so much verisimilitude a museum can do.

It took quite a while to work our way through these exhibits and, as usual, I knew we were absorbing only a small fraction of what they had to offer. So it is with large museums.

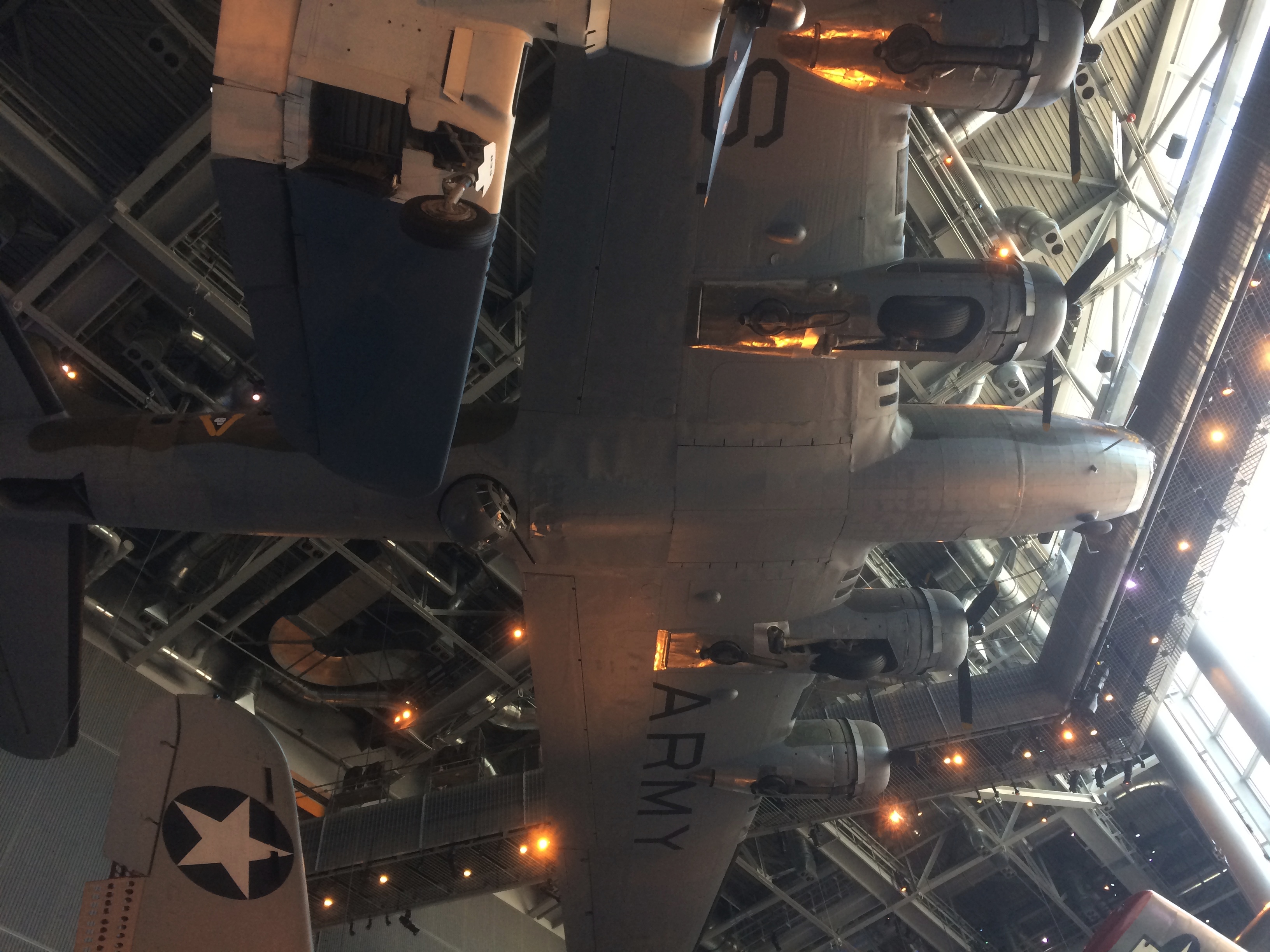

About 20 minutes before the museum closed, we arrived at the U.S. Freedom Pavilion: The Boeing Center. On display are airplanes, as you’d expect. Hanging from the high ceiling.

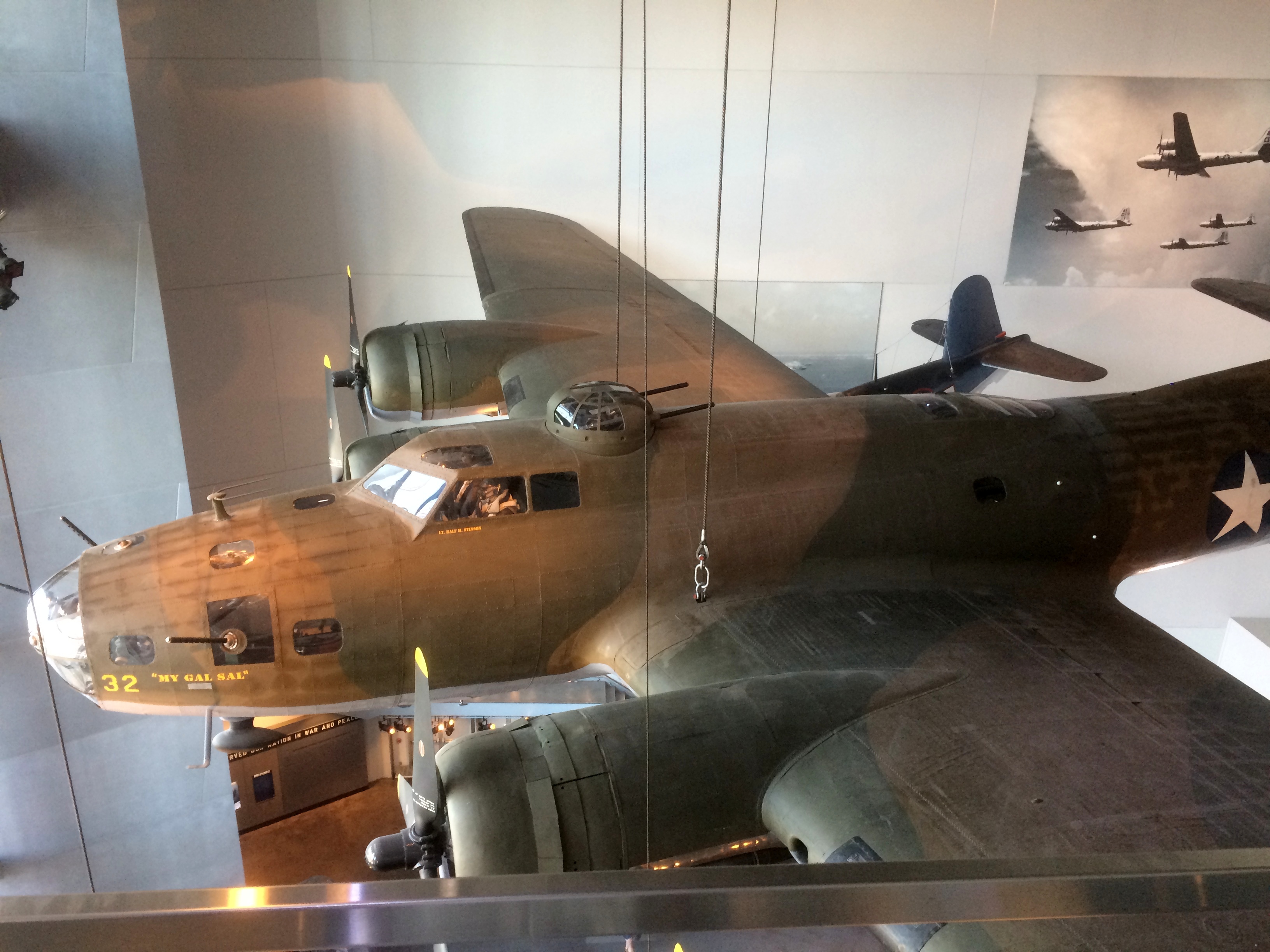

The centerpiece of the display is My Gal Sal, a B-17E Flying Fortress, one of only three or four such warplanes still in existence.

The centerpiece of the display is My Gal Sal, a B-17E Flying Fortress, one of only three or four such warplanes still in existence.

You can ride up to the fourth floor and look down on the plane.

You can ride up to the fourth floor and look down on the plane.

Heights don’t usually bother me from behind a secure railing, but looking down from above the plane, with it filling the void below me, made me a little unsettled.

Heights don’t usually bother me from behind a secure railing, but looking down from above the plane, with it filling the void below me, made me a little unsettled.

My Gal Sal probably survived because bad weather forced it to land in the wilds of Greenland in 1942, and it couldn’t fly again. The crew survived, but the plane stayed on the ice, not to be salvaged until the 1990s and restored in the early 21st century.

To the south of the trail at that point is an industrial complex belonging to Vita Plus. In its way, as interesting as anything we saw in Wisconsin that day.

To the south of the trail at that point is an industrial complex belonging to Vita Plus. In its way, as interesting as anything we saw in Wisconsin that day. The company provides “feed, nutrition and management expertise to dairy and livestock producers,” according to its web site.

The company provides “feed, nutrition and management expertise to dairy and livestock producers,” according to its web site. Still, it was a pleasant walk, crowded with neither bicyclists nor hikers. Phlox were a-bloomin’ along the trail.

Still, it was a pleasant walk, crowded with neither bicyclists nor hikers. Phlox were a-bloomin’ along the trail. Eventually we got to the trestle. Because I didn’t bother to check Google Images, I was expecting to see some kind of bridge substructure. The term “trestle” inspired that idea. Instead, we crossed a nice enough but not very dramatic bridge occupied by a few fishing enthusiasts.

Eventually we got to the trestle. Because I didn’t bother to check Google Images, I was expecting to see some kind of bridge substructure. The term “trestle” inspired that idea. Instead, we crossed a nice enough but not very dramatic bridge occupied by a few fishing enthusiasts. Views of Rock Lake from the trestle, to the north and to the south. Pyramids lurk under the waves, they say. Built by aliens, no doubt. To harness pyramid power and teach mankind to live in peace and harmony.

Views of Rock Lake from the trestle, to the north and to the south. Pyramids lurk under the waves, they say. Built by aliens, no doubt. To harness pyramid power and teach mankind to live in peace and harmony.

A local Nessie would be better, but I’ll pass along whatever tales are on offer.

A local Nessie would be better, but I’ll pass along whatever tales are on offer.