As of May 2019, Gen. Andrew Jackson still rides his steed at Jackson Square in New Orleans, the dramatic centerpiece of a handsome public space.

The equestrian bronze, by notable 19th-century sculptor Clark Mills, has been there since 1856, when the Battle of New Orleans was still in living memory, at least among the old timers. I understand the monument is a target of removalists, so there might come a day when Jackson Square loses its man on horseback and becomes Something Else Square.

The equestrian bronze, by notable 19th-century sculptor Clark Mills, has been there since 1856, when the Battle of New Orleans was still in living memory, at least among the old timers. I understand the monument is a target of removalists, so there might come a day when Jackson Square loses its man on horseback and becomes Something Else Square.

That’s New Orleans’ decision. Yet I’m not persuaded Jackson should go, for all his retroactively understood flaws. It’s one thing to remove monuments to those who actively sought disunion because they feared to lose their human property. Jackson and his men defeated an invading army on American soil near New Orleans. As president, he had no use for disunion, either. Just ask John C. Calhoun.

During our last day in New Orleans, Lilly and I visited the National WW II Museum, and to do so we got off the St. Charles streetcar at Lee Circle (as Google Maps calls it). Looking back at the circle, we saw an empty pedestal.

That’s odd, I said to Lilly. But I must have known at some time — I’d ridden on the St. Charles line decades earlier — that a statue of Robert E. Lee used to stand atop the pedestal. I’d forgotten. I don’t ever remember taking a close look at the Lee statue, since I haven’t always watched for monuments as much as I do now.

Just yesterday, it occurred to me to look up Lee Circle, and was reminded that removal activists were able to persuade New Orleans to take down Lee and three other monuments in 2017. Sic transit gloria mundi, Gen. Lee.

Of course, there are many ideas about a new statue to put on Lee’s former spot. Among this selection, the one I like best on prima facie examination is the relatively unknown J. Lawton Collins, a New Orleans native and important commander during WWII. He’s also appropriate because the museum devoted to that war is mere blocks away. Or if a strictly military option is out, Andrew Higgins, of Higgins boat fame, seems reasonable.

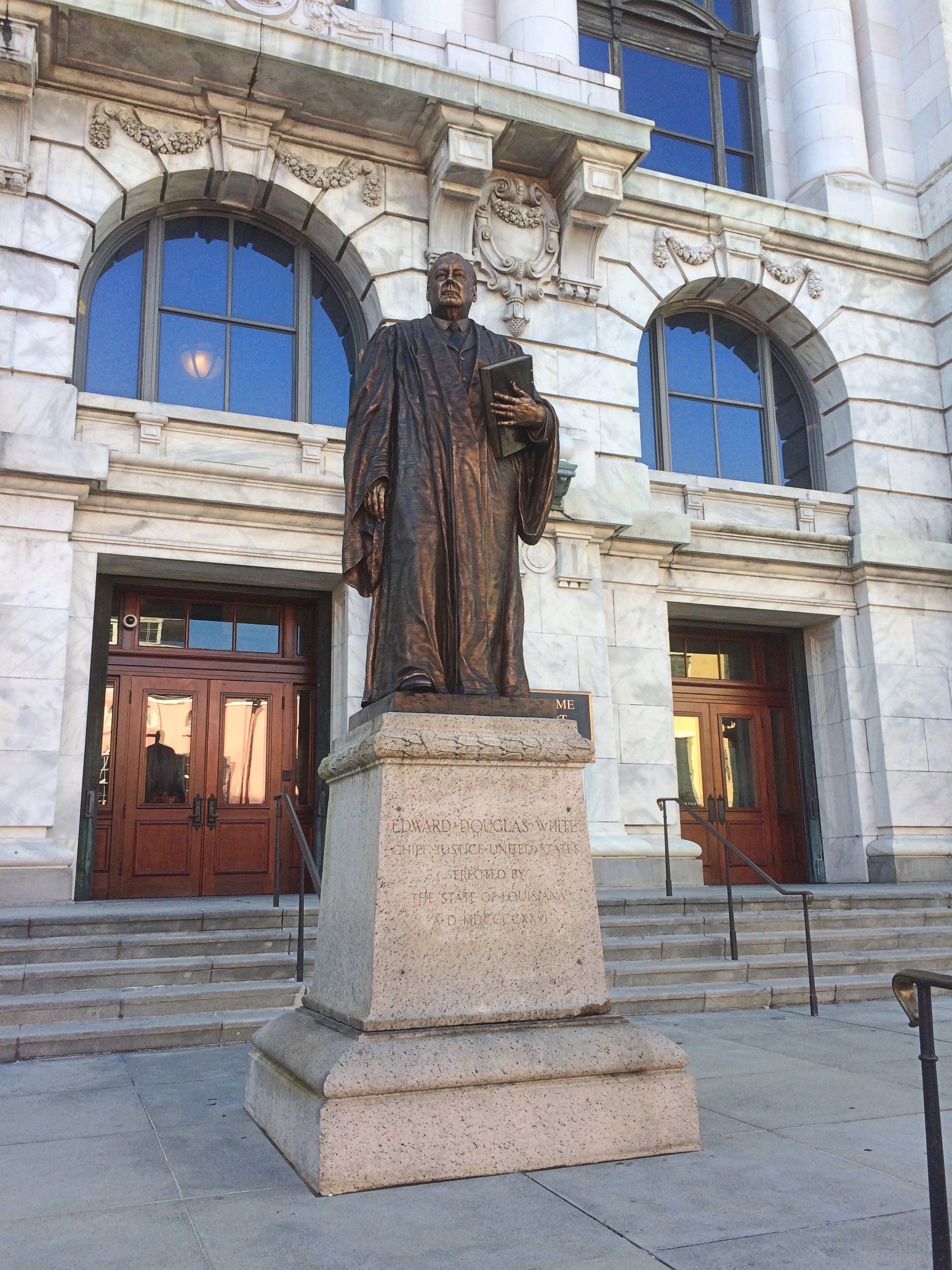

Here’s another statue that has gained the ire of removalists: Chief Justice of the United States Edward Douglass White Jr., who had a long and varied career but sided with the majority on the notorious Plessy v. Ferguson decision. (Most sources double that s in his middle name, but the statue does not.)

The chief justice stands on Royal St. in front of the major edifice housing the Louisiana Supreme Court, a building whose reputation has varied across the decades. We just happened to walk by.

Later I wondered, what’s the state supreme court doing in New Orleans and not Baton Rouge? Guess as far as the court is concerned, Baton Rouge is a johnny-come-lately capital, having that title only since 1846.

Chief Justice White would be a harder nut to crack for the removalists than Lee, simply because among the generally ahistoric American people, whipping up righteous outrage about someone as obscure as White would be a tall order. But it might happen.

In Louis Armstrong Park, where we had a pleasant stroll despite the increasing heat, there are plenty of statues that will probably last a good long time. Satchmo himself certainly deserves to.

Elizabeth Catlett did the bronze, which was dedicated in 1980.

Elizabeth Catlett did the bronze, which was dedicated in 1980.

Other metal jazzmen grace the park, such as a marching brass band by sculptor and New Orleans native Sheleen Jones-Adenle, erected in 2010.

Here’s a tripartite statue of foundational jazzman Charles ‘Buddy’ Bolden created by sculptor Kimberly Dummons, also from 2010. Such triple figures aren’t common, but not unknown.

Here’s a tripartite statue of foundational jazzman Charles ‘Buddy’ Bolden created by sculptor Kimberly Dummons, also from 2010. Such triple figures aren’t common, but not unknown.

In Congo Square, there’s a vivid sculptural relief by Nigerian-born artist Adéwálé Adénlé fittingly called “Congo Square,” another of the 2010 class of works in the park.

That hardly covers everything in Louis Armstrong Park. Whoever Mike is, he made good images of these and other sculptures there.

Next to the French Market, at St. Philip and Decatur Sts., is Maid of Orleans, a gift from France to New Orleans and erected in 1972.

A replica of the 1880 Emmanuel Frémiet equestrian statue of Joan of Arc in Place des Pyramids in Paris, the Maid used to be at the foot of Canal St., but when a casino was developed there, she moved to her present location in the Quarter.

A replica of the 1880 Emmanuel Frémiet equestrian statue of Joan of Arc in Place des Pyramids in Paris, the Maid used to be at the foot of Canal St., but when a casino was developed there, she moved to her present location in the Quarter.

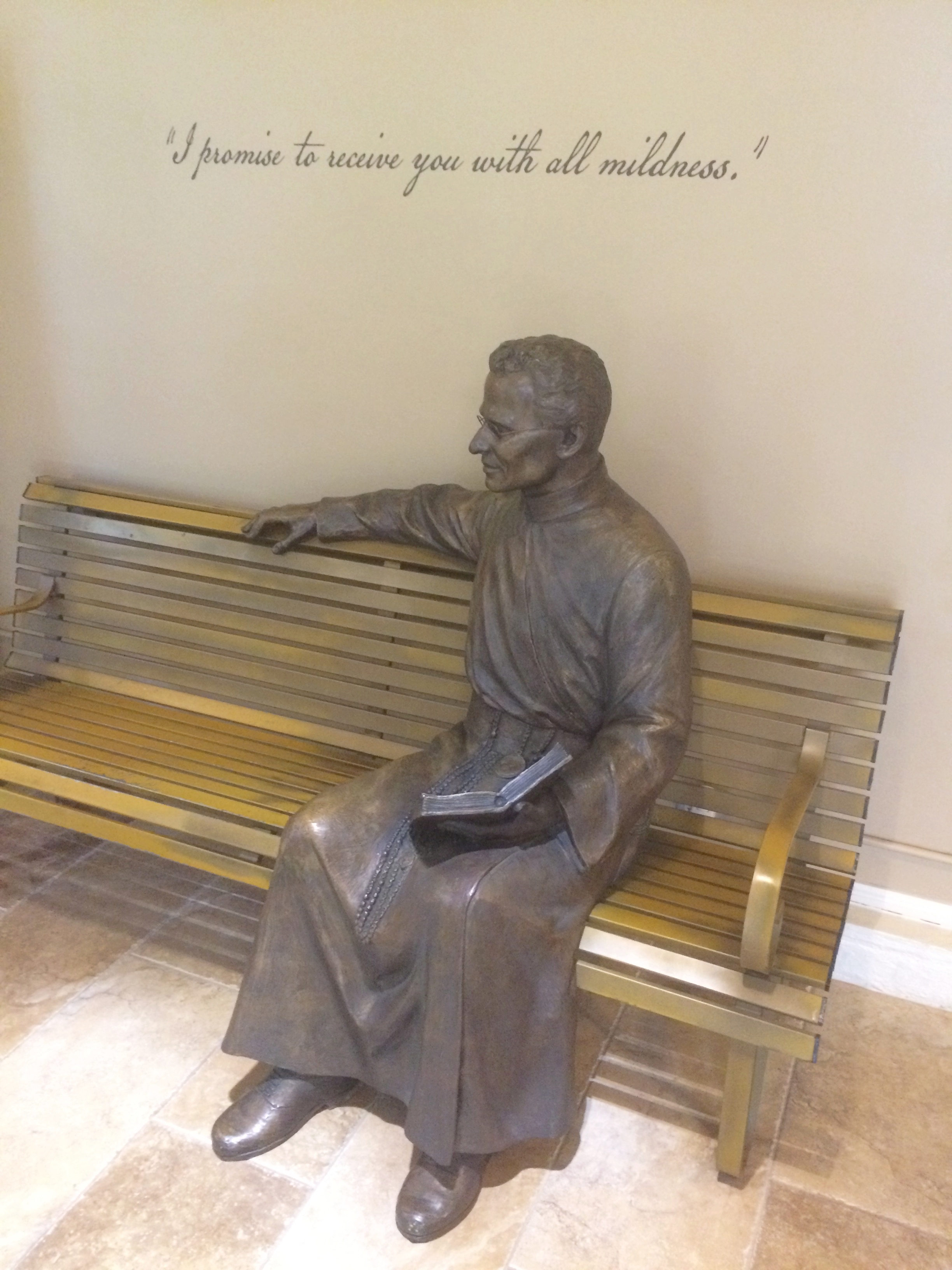

One more: A seated statue of Francis Xavier Seelos.

How we came see that statue, during our walkabout in the Garden District, is slightly convoluted. But that’s never stopped me from pursuing a destination.

How we came see that statue, during our walkabout in the Garden District, is slightly convoluted. But that’s never stopped me from pursuing a destination.

While relaxing at the Chateau Hotel during the second evening, I queued up “Pearl of the Quarter,” a dulcet song about a New Orleans long gone and which never quite was. One of its lines: “I met my baby by the shrine of the martyr.”

A flight of Steely Dan fancy, I’m sure, but if you Google around using that term and “New Orleans,” pretty soon you come across the National Shrine of Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos at St. Mary’s Assumption Church in New Orleans. Which just happened to be not too far from where we were going to go the next day.

So we visited the shrine and its reliquary, which are separated from the nave of the church by a wall and a door — locked. We didn’t get to see the interior of the church as a result, which I understand is well worth seeing.

The seated statue is in the hallway outside the shrine itself, which includes a number of exhibits about Fr. Seelos, a Redemptorist from Bavaria, along with many relics and a more conventional standing statue of him at the end of the hall.

Fr. Seelos, for his part, was beatified by the church in 2000. He came to New Orleans as a missionary in the 1866.

“As pastor of the Church of St. Mary of the Assumption, he was… joyously available to his faithful and singularly concerned for the poorest and the most abandoned,” Seelos.org says.

“In God’s plan, however, his ministry in New Orleans was destined to be brief. In the month of September, exhausted from visiting and caring for the victims of yellow fever, he contracted the dreaded disease. After several weeks of patiently enduring his illness, he passed on to eternal life on October 4, 1867.”