The Chicago Architecture Foundation calls one of its new tours Hotel Boom. “Learn how and why a former athletic club, bank, chemical company, motor club and more were transformed into first-class hotels,” the description promises. I was game. So we (all of us, including Ann) took the tour on Easter Saturday, a warm, pleasant spring day in Chicago.

I suspected that I’d been in many of the properties, and I was right. But some of them weren’t even hotels the last time I visited, and it’s always good to hear about a property from a knowledgeable docent, which CAF docents tend to be. In order, we visited the Silversmith Hotel, Virgin Hotel, Hampton Inn (formerly the Chicago Motor Club Building; I got an international drivers license there), London House, Hard Rock Chicago, and the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel.

Mostly we got a look at the exteriors, and then at the lobbies, though at one property we didn’t enter the lobby, and at another we saw the rooftop.

My friend Geof Huth stays at the Silversmith Hotel, 10 S. Wabash Ave., when he’s in town. The exterior is an historic arts-and-crafts facade dating from the 1890s, done by one of Daniel Burnham’s men. I assume that silversmiths were once tenants, since that part of Wabash was Jewelers Row (and still is). When I met Geof there in previous years, the lobby interior — which is not a protected historic feature — looked like this, with brown predominating. Not any more. Now black and off-white is the thing in the Silversmith’s public areas.

Next up was the Virgin Hotel. Virgin as in one of Sir Richard Branson’s properties, and in fact the first hotel with that flag, opened only in 2015. This was a surprise. I used to work across the street, more-or-less, and I remembered the Old Dearborn Bank Building at 203 N. Wabash Ave. being an interesting but aged art deco building.

The exterior has been spiffed up, the better to appreciate some of the details.

We had to skip the interior. One of these days I might take a look.

We had to skip the interior. One of these days I might take a look.

There’s a Hampton Inn in what used to be the Chicago Motor Club Building at 68 E. Wacker Pl., originally developed in 1928 and converted into a hotel only a few years ago.

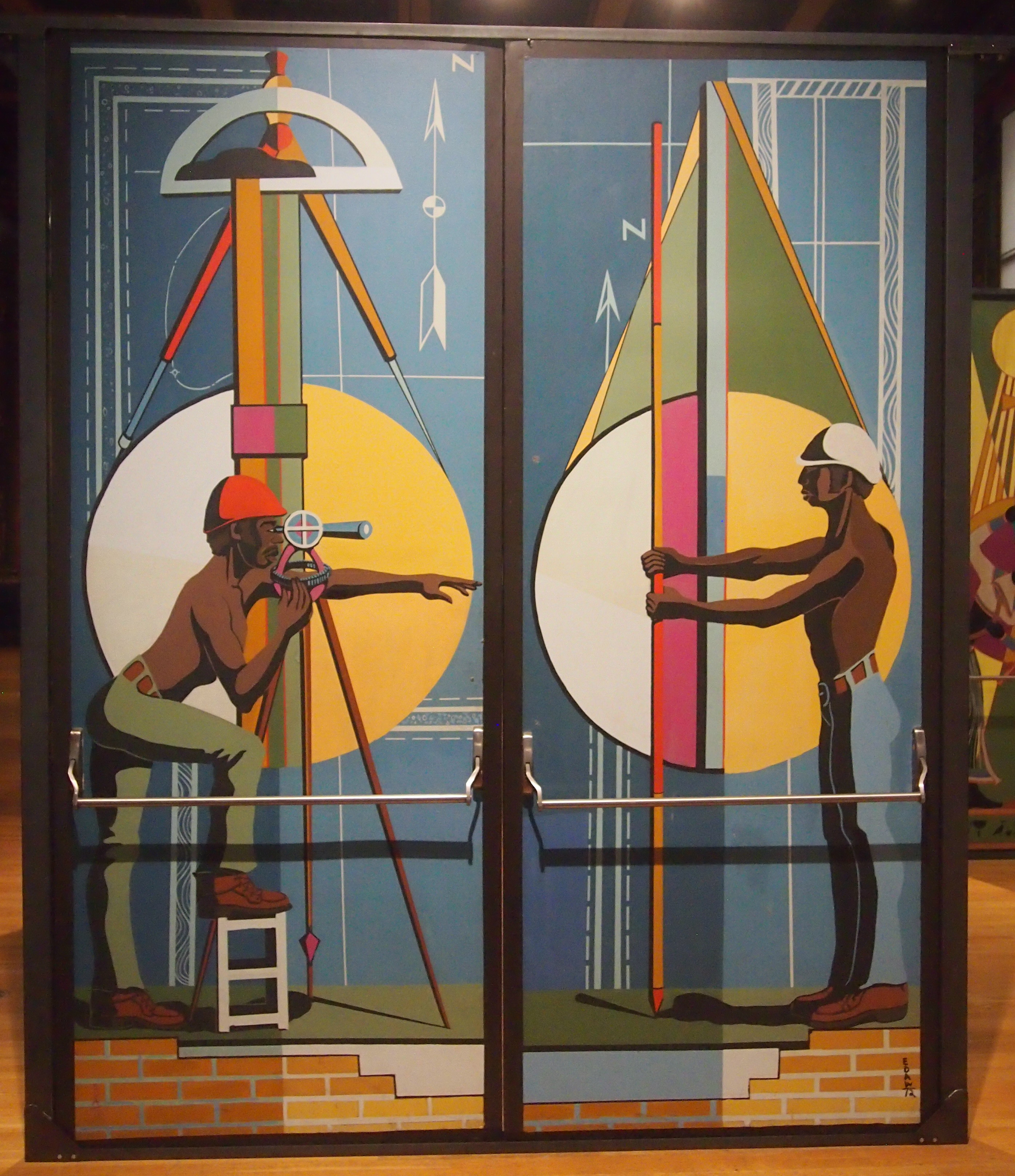

Blair Kaiman writes: “All of Art Deco’s defining characteristics are compressed into this fabulous, 15-story package just west of Michigan Avenue: A trim silhouette with strong vertical lines; stylish geometric decoration; and a superb integration of art and architecture, especially in the lobby where a freshly restored mural map of the continental United States reigns with regal understatement.”

Blair Kaiman writes: “All of Art Deco’s defining characteristics are compressed into this fabulous, 15-story package just west of Michigan Avenue: A trim silhouette with strong vertical lines; stylish geometric decoration; and a superb integration of art and architecture, especially in the lobby where a freshly restored mural map of the continental United States reigns with regal understatement.”

It’s a splendid mural. Done by an Illinois artist named John Warner Norton (1876-1934), who favored this kind of large work. More about him here, by a writer who doesn’t understand paragraphs.

It’s a splendid mural. Done by an Illinois artist named John Warner Norton (1876-1934), who favored this kind of large work. More about him here, by a writer who doesn’t understand paragraphs.

I like this detail, too. It’s over the hotel’s main entrance.

The Hard Rock Hotel Chicago at 230 N. Michigan Ave. is a Hard Rock. With that, you get musical embellishments, such as guitars on the wall and an express checkout station that’s fashioned out of a 45 record player.

The Hard Rock Hotel Chicago at 230 N. Michigan Ave. is a Hard Rock. With that, you get musical embellishments, such as guitars on the wall and an express checkout station that’s fashioned out of a 45 record player.

The hotel is the Carbide and Carbon Building, yet another fine deco building, finished in 1929, just before the Depression ground building to a halt, deco or otherwise. Burnham Bros. did the original building (Daniel Burnham was long dead by then); Lucien Lagrange Architects did the conversion into a hotel, finished in 2003.

You might even call it noir deco, since carbon black is the motif.

Further south, fitting very nicely in the Historic Michigan Boulevard District, is the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel at 12 S. Michigan.

Further south, fitting very nicely in the Historic Michigan Boulevard District, is the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel at 12 S. Michigan.

The building, a Henry Ives Cobb design, goes all the way back to 1893, so it was spanking new at the time of the World’s Fair. No art deco for him. He was of a previous generation. He also did the Newberry Library, which I’ve always liked, and the fine Yerkes Observatory.

The building, a Henry Ives Cobb design, goes all the way back to 1893, so it was spanking new at the time of the World’s Fair. No art deco for him. He was of a previous generation. He also did the Newberry Library, which I’ve always liked, and the fine Yerkes Observatory.

The redevelopment of a posh men’s club into a posh hotel by Hartshorne Plunkard Architecture was finished only in 2015. “Many of the building’s elaborate architectural details were preserved, as the ornate millwork and tiled floors throughout the interior and the stained glass and cast-iron exterior relief have all been restored,” says Curbed Chicago. “However, one of the greatest highlights of the new hotel is its rooftop restaurant’s deck space that offers sweeping views of Michigan Avenue and Millennium.”

On a pleasantly warm Saturday, the line to get to the elevator to the rooftop was long indeed. Some other time, maybe.

We did see the large bar on the first floor. It features a lot of games and a sports theme on the walls. Sports of an earlier time: leather football helmets, baggy golf knickers, and medicine balls.

The space also included a bocce ball court. People were playing it. I’d never seen anyone play bocce ball.

Guess I don’t hang around enough Millennial bars. Or any bars, come to think of it.

Guess I don’t hang around enough Millennial bars. Or any bars, come to think of it.