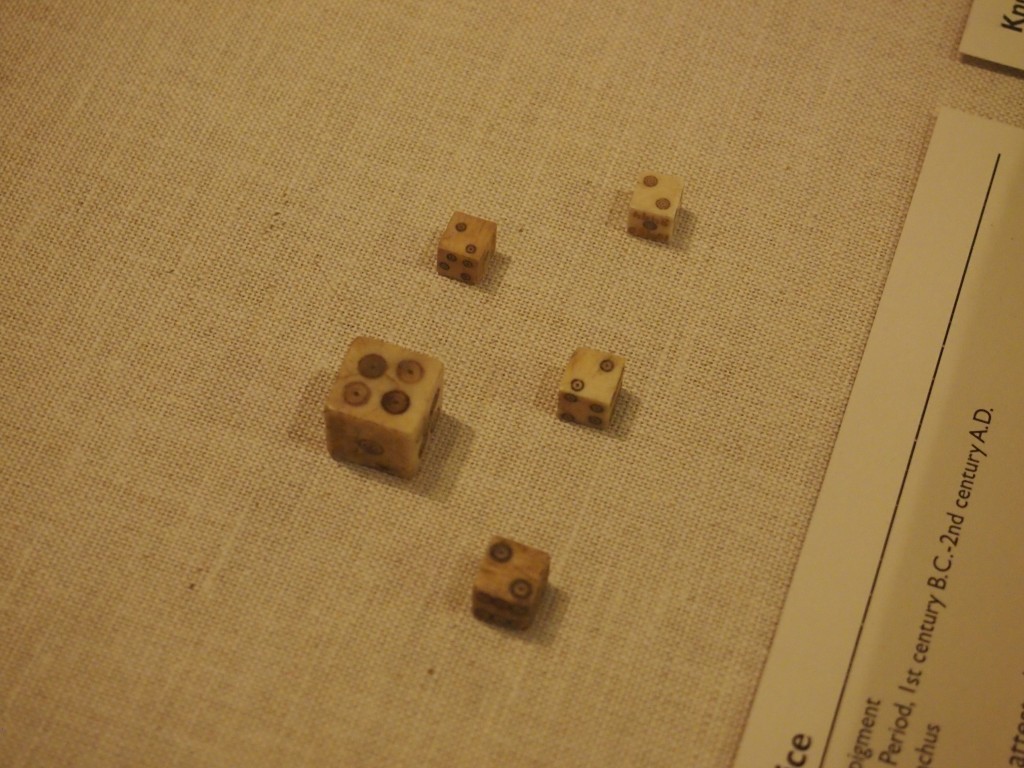

Last week I took note of some of the monumental items at the Oriental Institute Museum, but of course the museum is home to a lot more artifacts, and most of them were more modest in size. But no less interesting for it. Such as some dice from Roman Egypt.

Cool. Especially since anyone alive now, two millennia after they were made, could look at them and know exactly what they’re for, even if the games of chance aren’t quite the same. Even cooler is that dice were ancient even then, so much so that their origin is obscure.

Cool. Especially since anyone alive now, two millennia after they were made, could look at them and know exactly what they’re for, even if the games of chance aren’t quite the same. Even cooler is that dice were ancient even then, so much so that their origin is obscure.

Also on display were some knucklebones, an alternative to dice that are probably just as old, if not older (and the ancestor of modern playing jacks?). According the museum, “knucklebones of sheep or oxen were used to determine the number of moves on game boards. The four sides of each bone are distinctive, and each was assigned a specific number. They were normally thrown in pairs, allowing for ten possible combinations.”

The museum also sported plenty of figurines.

Still charming after all these centuries. Thought to come from a tomb of a courtier named Nykauinpu at Giza, made of limestone and dating from the Old Kingdom, Dynasty 5 of the 25th century BC. So by the time of Julius Caesar, this statue was already older than anything from the time of Julius Caesar is now. Even on a human scale (not to mention geological or cosmological), time’s mind-boggling.

Still charming after all these centuries. Thought to come from a tomb of a courtier named Nykauinpu at Giza, made of limestone and dating from the Old Kingdom, Dynasty 5 of the 25th century BC. So by the time of Julius Caesar, this statue was already older than anything from the time of Julius Caesar is now. Even on a human scale (not to mention geological or cosmological), time’s mind-boggling.

On a sign describing another man-and-woman set of Egyptian figurines, I noted these lines, referring to the way the woman was dressed (emphasis added): “This style of dress was popular for the entire 3,000 years of pharaonic history.” I’ll say one thing about the ancient Egyptians — they found something they liked and stuck with it.