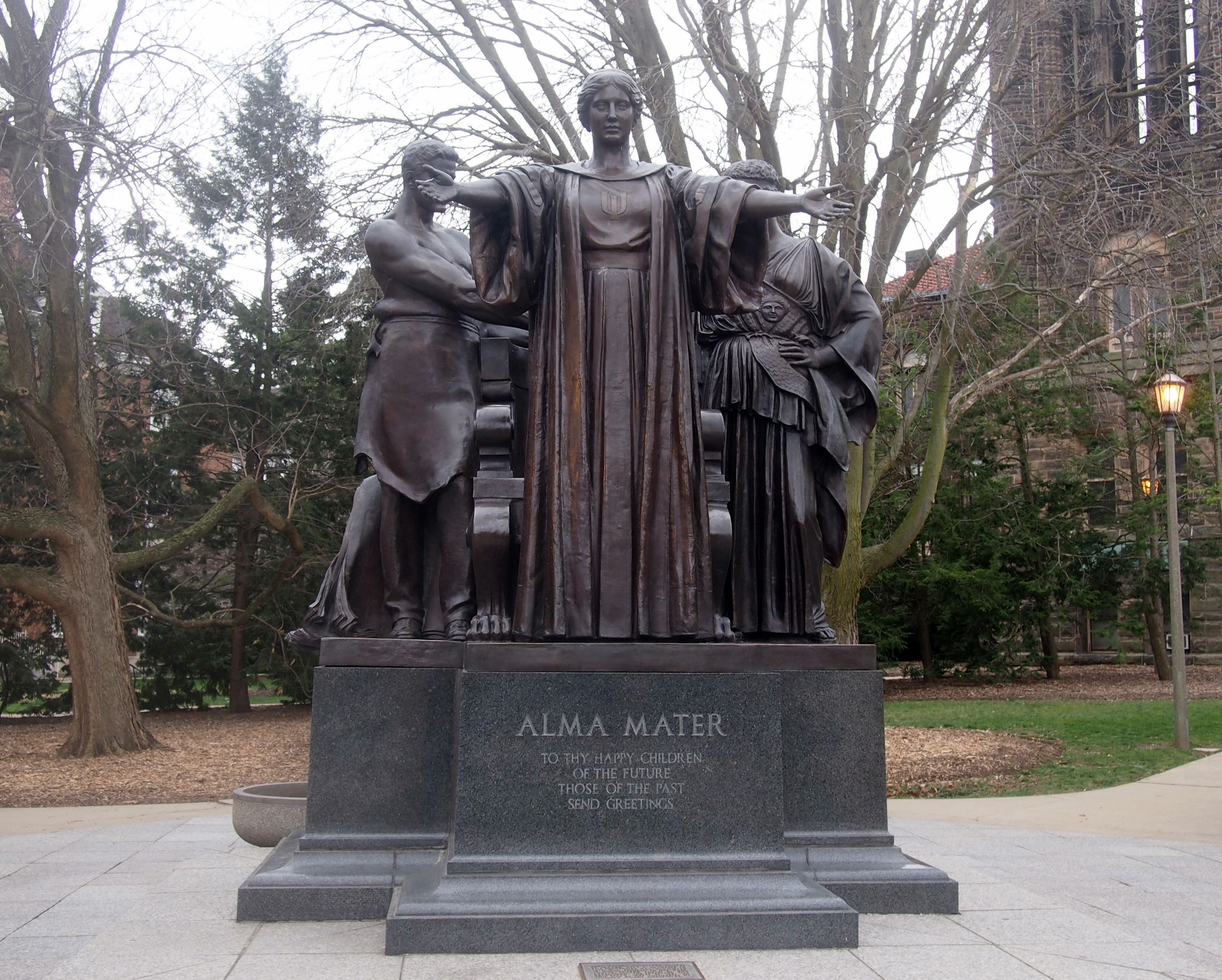

Most Chicago Architectural Foundation tours begin at 224 S. Michigan Ave., where the foundation is located and which is also known as the Santa Fe Center or, originally, the Railway Exchange Building. It’s a handsome structure by Daniel Burnham, dating from 1904.

“A building around a light well, a form common to Daniel H. Burnham’s work from the mid-1880s onward, received an undulating white-glazed terra-cotta skin, oriel bays, and a top floor of distinctive porthole windows,” notes the AIA Guide to Chicago. “As in the Rookery, there is a two-story covered court at the base of the light well dominated by a grand staircase.”

The view from near the grand staircase.

Note the model of Chicago taking up much of the floor. At 25 by 35 feet, it’s an exact model of every building in more than four square miles of the city, or more than 1,000 of them. The obviously skilled Columbian Model & Exhibit Works created it for the Chicago Architectural Foundation in the late 2000s.

Note the model of Chicago taking up much of the floor. At 25 by 35 feet, it’s an exact model of every building in more than four square miles of the city, or more than 1,000 of them. The obviously skilled Columbian Model & Exhibit Works created it for the Chicago Architectural Foundation in the late 2000s.

The Tribune reported in 2009 that the “model buildings came from Columbian’s workshop. The exhibit is broken down into 400 city blocks, in squares the size of dinner plates carried in food caterer’s serving carts. With the buildings already glued in place, the blocks were placed into the exhibit like waiters carefully placing food plates into a buffet table.

“[Foundation VP Gregory] Dreicer said the first step in the process was creating a digitized three-dimensional computer model of the city that could be manipulated on a screen. The designers did it using architectural drawings or drawings purchased from commercial firms that collect such information.

“To make each building, they went to firms that use the three-dimensional printing process called stereolithography, used to make design prototypes of various products like plastic containers for food, cleaning or pharmaceutical products.”

Wow. That’s impressive. And right there, for anyone to walk in and see, no charge. It’s not a static display, either. I’ve read that the CAF updates it periodically, as buildings come and go in Chicago.