The plan was to spend a few hours in Memphis on June 25 on the way to Little Rock, where we’d overnight. The question then became, was Graceland worth visiting? The least expensive adult ticket, just for getting into the house and grounds to look around, is $42.50. For $80, you can also see a whole lot of stuff that isn’t the house and grounds, such as Elvis airplanes and cars and whatnot (“Experience Graceland like you are a VIP plus see Elvis’ custom jets!”)

Two strikes. I understand how it works. The prices are whatever the market bears. I don’t care, I still think they’re insane. Maybe temporary insanity, fading as the generation that originally adored Elvis passes from the Earth. Who knows?

The third strike was Graceland’s distance south of I-40, the road from Nashville to Little Rock. Elvis very nearly lived in Mississippi.

So I turned my attention to the National Civil Rights Museum, which is practically in downtown Memphis, not far at all from the highway. Adult admission, $15. After lunch that day, we repaired to the museum, which is behind the facade of the former Lorraine Motel, site of MLK’s assassination. Under Jim Crow, the Lorraine was a place where black people could stay.

The motel sign is still in place, though the marque message isn’t original. Wonder what it said in 1968.

A wreath hangs at the site of Dr. King’s death. I’ve seen photos of the place for years, so it was quite a thing to see it in person.

A wreath hangs at the site of Dr. King’s death. I’ve seen photos of the place for years, so it was quite a thing to see it in person.

The plaque says:

The plaque says:

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR

Jan 15, 1929 – Apr 4, 1968

Founding President

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

“They said one to another

Behold here, cometh the dreamer.

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dreams.”

Genesis 37:19-20

Ralph David Abernathy, President

The museum, which opened in 1991, isn’t strictly devoted to MLK, however. It’s considerably broader than that, with the two-story building behind the Lorraine facade focusing on the years of the civil rights struggle between 1954 to 1968, though there are exhibits that the set the stage, so to speak — about slavery and then Jim Crow — and exhibits covering more recent years. The exhibits are organized chronologically through those years.

Like any good history museum, the displays are a mix of images, reading materials, interactive features, and artifacts, some quite large. As the NYT described it in 2003 (before a 2014 renovation, which apparently added more interactive features): “Rather than simply displaying photos and documents about the Montgomery bus boycott, for example, there is an actual bus like those that were used in Montgomery in the 1950s. Visitors may climb aboard, and after they sit down, a recorded voice begins by asking them politely to move to the back and then, if they refuse, rises to angry commands.”

Here’s the bus.

Inside is a statue of Rosa Parks.

Inside is a statue of Rosa Parks.

I was glad to see that the museum explained Parks’ action was carefully planned to achieve certain goals, with Parks fully part of that plan, and not some spontaneous act by a tired woman, which is the impression you sometimes get hearing about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

I was glad to see that the museum explained Parks’ action was carefully planned to achieve certain goals, with Parks fully part of that plan, and not some spontaneous act by a tired woman, which is the impression you sometimes get hearing about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

“Nearby is a reconstruction of a lunch counter like the ones where protesters sat as they tried to break the color barrier that was an almost unquestioned part of Southern life until 50 years ago,” the NYT continues. “Life-size figures sit at the counter, and a video shows how the protesters prepared for the ordeal of insults, condiments poured on their heads and other humiliations.”

Plenty of other ground is covered, including the March on Washington — Dr. King’s entire speech is played, not just the usual highlights — Freedom Summer, Freedom Rides, Birmingham, Selma, Albany, Ga., the murders in Philadelphia, Miss., the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and more. I grew up hearing about the tail end of this period, and learning about it later, but even so, some of the detail was new to me. I expect most of it was new to Ann.

Plenty of other ground is covered, including the March on Washington — Dr. King’s entire speech is played, not just the usual highlights — Freedom Summer, Freedom Rides, Birmingham, Selma, Albany, Ga., the murders in Philadelphia, Miss., the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and more. I grew up hearing about the tail end of this period, and learning about it later, but even so, some of the detail was new to me. I expect most of it was new to Ann.

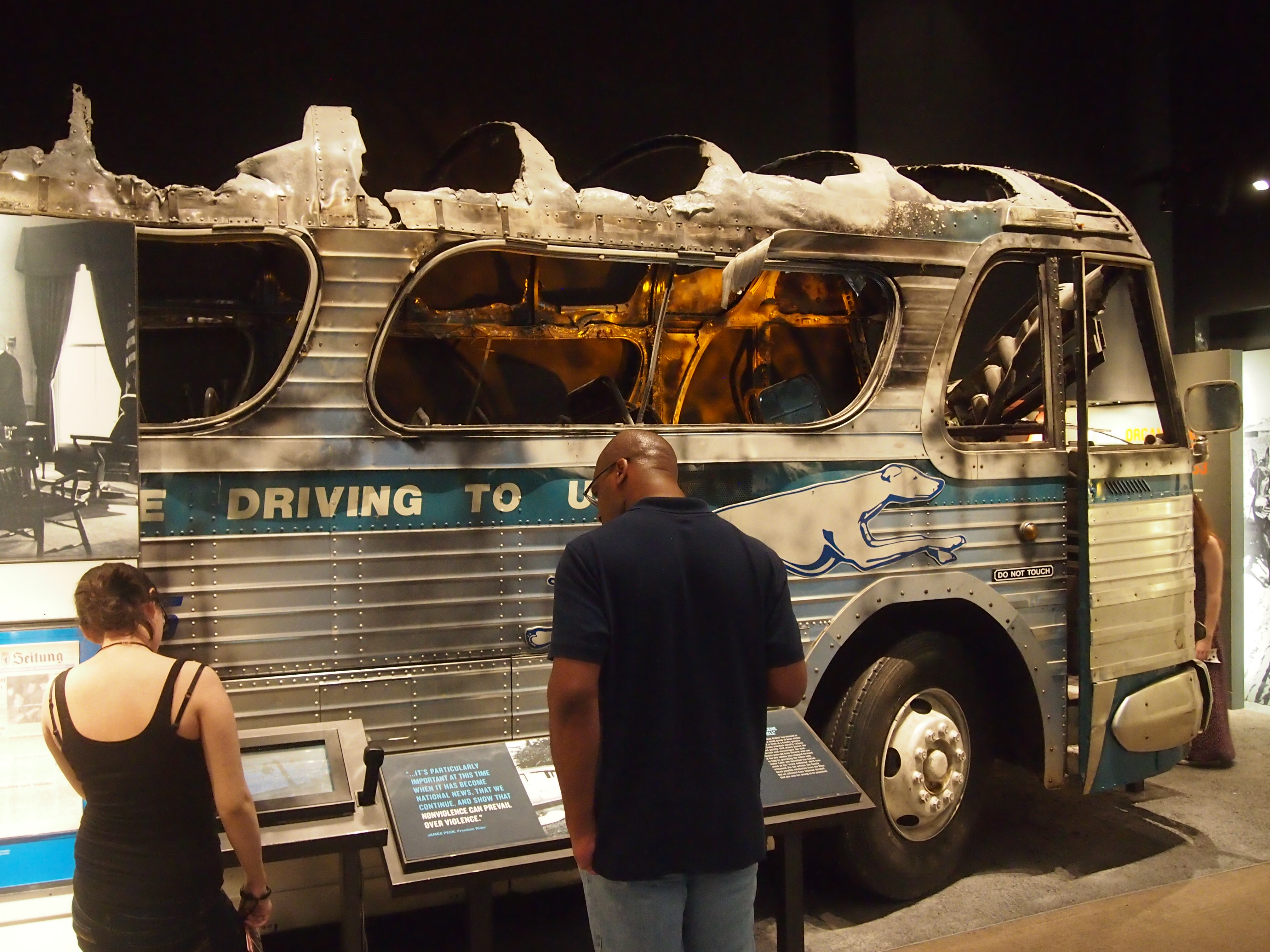

Here’s another bus, a replica of a torched Freedom Riders bus.

Eventually you reach reach the two preserved motel rooms (306 and 307), the one MLK stayed in and the one next to it, that are designed to look like they did the day he died. Visitors are able to peer into them but not go in.

Eventually you reach reach the two preserved motel rooms (306 and 307), the one MLK stayed in and the one next to it, that are designed to look like they did the day he died. Visitors are able to peer into them but not go in.

Across Mulberry St. are the Young & Morrow Building and the Main Street Boarding House, now forming an annex to the museum. The annex is more closely focused on the assassination of Dr. King, and includes a reconstruction of the room from which James Earl Ray squeezed off the fatal shot, including artifacts — evidence — of the crime. It reminded me of the Sixth Floor in that way. And while there’s a also display called “Lingering Questions,” I don’t doubt that Ray, like Oswald before him, was guilty as hell, as my Uncle Ken would have put it.

Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Jacqueline Smith. For some years after MLK’s death, the Lorraine operated as an SRO, and she was a resident — the last one kicked out to make way for the museum. Since then, she’s parked herself across the street in protest (though perhaps she finds substitutes sometimes).

Someone was there, barely visible under an umbrella and behind the signs. Twenty-eight years and 150 days of protest as of June 25, according to one of the signs. Whatever else you can say about her, she’s stuck to her cause.

Someone was there, barely visible under an umbrella and behind the signs. Twenty-eight years and 150 days of protest as of June 25, according to one of the signs. Whatever else you can say about her, she’s stuck to her cause.

Wonder who left the shells. Not far away is the poet

Wonder who left the shells. Not far away is the poet