In late May, I benefited from a bit of service journalism offered by the Chicago Tribune, which told me that the state of Wisconsin wasn’t charging entry fees to state parks on the first weekend in June.

So on June 2, we sought to take advantage of the situation by driving up to Wisconsin for the day — and probably proving the marketing arm of the state right when it calculated that such an offering would attract some out-of-state visitors, especially from Illinois.

Before we went to any state park, however, we stopped in the pleasant town of Lake Mills, which is in Jefferson County in the southern part of the state, between Madison and Milwaukee. We had a satisfying lunch at a diner called Cafe on the Park, which is on Main St. across the street from Commons Park. Then we took a stroll over to the park.

Visible from the park are some interesting buildings, such as the former Odd Fellows Hall and local opera house. Now it’s occupied by an antique mall.

The charming Lake Mills Public Library. Closed on Sunday, or I would have gone in.

There’s a bandstand in the park. Wouldn’t be a proper small-town park without one. With patriotic bunting. Nice touch. Formally it’s the Franklin Else Memorial Bandstand, though you (I) could argue it’s a large gazebo.

The Veterans Monument in the park is a little odd. It’s respectful and all, but has some unusual design elements.

It has a triangular shape, for one thing, with three triangular columns rising from a triangular base to support a triangular top. Triangles are also etched into the design in various places.

It has a triangular shape, for one thing, with three triangular columns rising from a triangular base to support a triangular top. Triangles are also etched into the design in various places.

Besides all that, a black stone pyramid is the centerpiece of the memorial. Why? Or, if you’re feeling more surprised, WTF?

Besides all that, a black stone pyramid is the centerpiece of the memorial. Why? Or, if you’re feeling more surprised, WTF?

No marker on or near the monument explains. I didn’t know what to make of that local oddity until I got home and looked around some.

Twenty years ago, the Tribune published an article about Lake Mills and its adjacent body of water, Rock Lake.

“There’s something in Rock Lake.

“What, exactly, lies at the bottom of this placid fishing hole east of Madison is the stuff of local legend, the obsession of scores of divers and the spark of an unlikely controversy that has raged among locals for decades.

“Believers, including many old-timers and diving enthusiasts, say that ancient pyramids, ruins and even a serpent-like, 200-foot-long rock figure lay beneath these algae-filled waters. They say pre-Columbian dwellers built the structures on dry land before the area was flooded by geological upheavals and a dam built in the 1800s.

“Skeptics… say there’s nothing but natural piles of rocks below the 40-foot depths…. the otherwise unremarkable town of Lake Mills, which abuts Rock Lake, [calls] itself ‘City of the Pyramids.’ “

City of Pyramids, eh? Sounds like something a ’30s newspaperman made up and a ’50s chamber of commerce ran with. A little whimsical to incorporate into a veterans memorial, no? Then again, do such memorials need to be somber to the point of sameness, ignoring local lore?

That’s hardly the end of online descriptions of the supposed structures at the bottom of Rock Lake. Grazing through some of them, you come up with lines like:

“You can’t mistake certain things. There’s a city down there. There’s no question about it.”

“There are remarkable, artificial underwater structures beneath the waters of Rock Lake, Wisconsin but unfortunately for many years these prehistoric ruins have been ignored by researchers.”

“Much like Judge Hyer before him, Taylor believed that the three to four pyramids (the number changed with each reporting) was [sic] Aztec in origin and were built during a drought when the lake was completely drained and they were sacrificial altars to the rain god to bring the rains back.”

“Aerial photos, side boat sonar scans, and underwater divers eventually charted a complex of at least nine different stone structures, including: two rectangular pyramids, several stacked-rock walls, two ‘Stone Cone’ areas, a conical pyramid, and a large ‘Delta Triangle’ structure.”

“Former state archaeologist Bob Birmingham told the Wisconsin State Journal in 2015 that the tales were ‘a bunch of baloney.’ ”

Bob Birmingham chalks up the shapes to piles of rock left by receding glaciers, and notes that such piles are found in other Wisconsin lakes. My, that’s boring. Tales of ancient peoples building mysterious structures are awfully romantic.

Somehow, I’m inclined to agree with Bob.

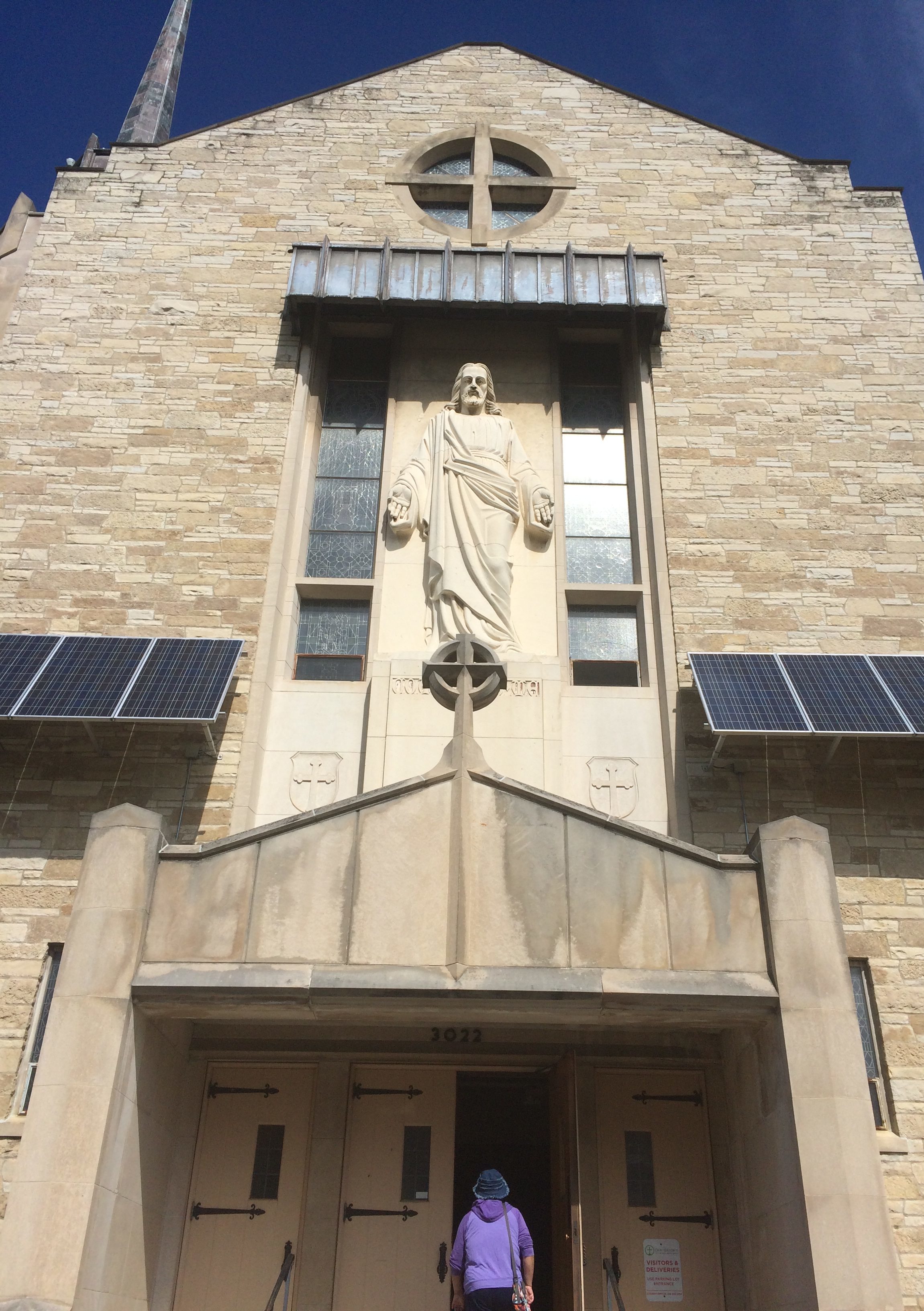

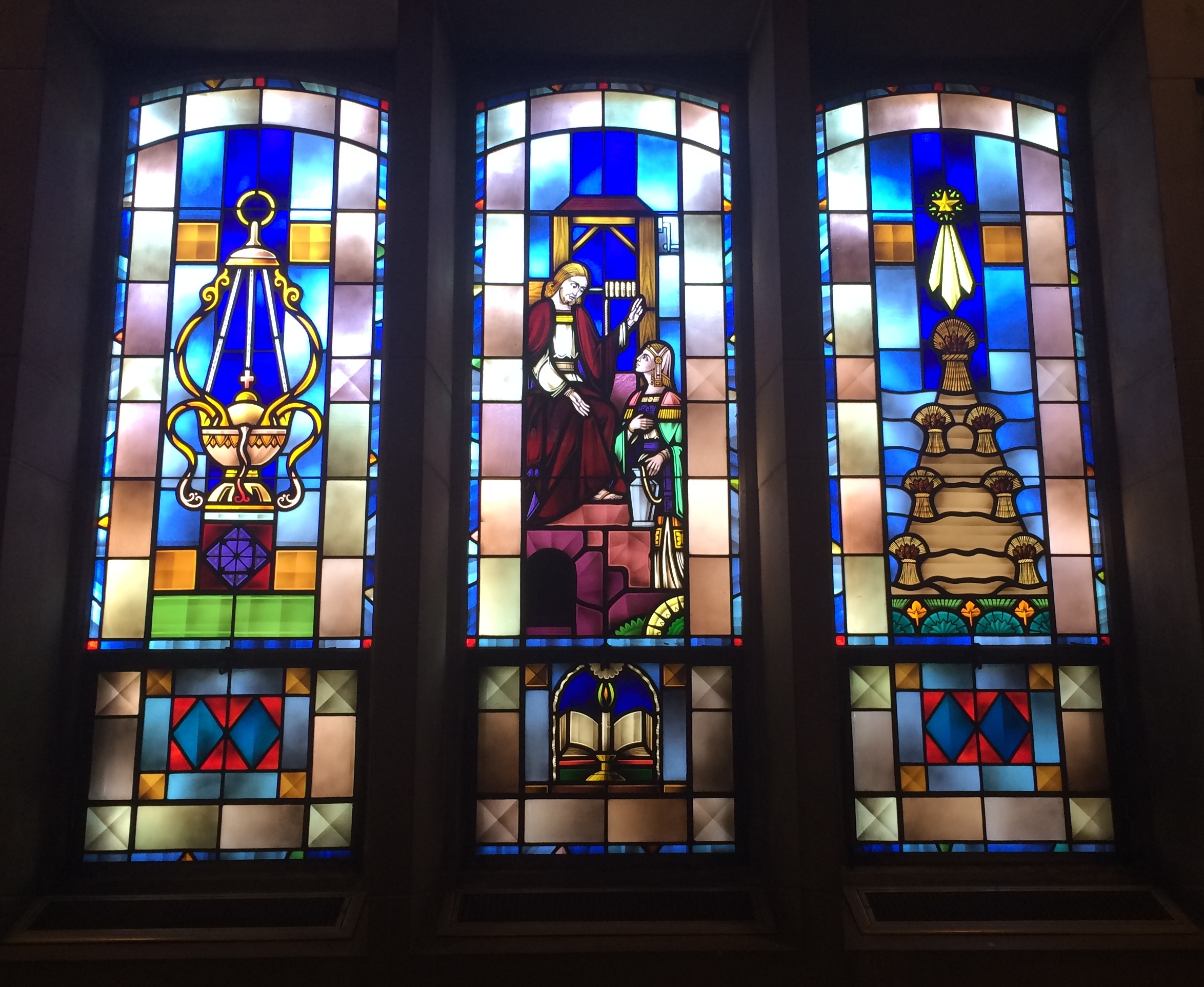

Though the Melkites are in communion with Rome, I was expecting an Eastern-style church inside. Mostly, it is, with icons and an iconostasis and Christ on the ceiling. But it also includes pews.

Though the Melkites are in communion with Rome, I was expecting an Eastern-style church inside. Mostly, it is, with icons and an iconostasis and Christ on the ceiling. But it also includes pews. One of the congregation was on hand to tell us about the church, and his idea was that the pews were a bit of syncretism on the part of the Lebanese and Syrian founding families of the church, or maybe the architect, one Erhard Brielmaier. Also, the church didn’t have icons in its early days, those being added in more recent decades, which might explain why their language is English.

One of the congregation was on hand to tell us about the church, and his idea was that the pews were a bit of syncretism on the part of the Lebanese and Syrian founding families of the church, or maybe the architect, one Erhard Brielmaier. Also, the church didn’t have icons in its early days, those being added in more recent decades, which might explain why their language is English.

Christ on the ceiling is a particular admirable work.

Christ on the ceiling is a particular admirable work. I was astonished to learn that it isn’t a painting, which it very much looks like, but a printed image made using a highly sophisticated machine and fixed in place.

I was astonished to learn that it isn’t a painting, which it very much looks like, but a printed image made using a highly sophisticated machine and fixed in place. That was a long time before the highway, unfortunately next to the church, was built.

That was a long time before the highway, unfortunately next to the church, was built. Nickname: the Big Red Church.

Nickname: the Big Red Church. Inside, I was surprised again.

Inside, I was surprised again. “Not what you expected, is it?” said one of the congregation. He explained that with pews, the church would be used once a week for a few hours — unsustainable for a small membership. Twenty years ago, they decided to remove the pews. When the congregation meets now, it’s on temporary chairs under a multi-petal canopy. Other groups also meet for other purposes in the now-open space, making the place an active one.

“Not what you expected, is it?” said one of the congregation. He explained that with pews, the church would be used once a week for a few hours — unsustainable for a small membership. Twenty years ago, they decided to remove the pews. When the congregation meets now, it’s on temporary chairs under a multi-petal canopy. Other groups also meet for other purposes in the now-open space, making the place an active one.